Honor Thy Father (2 page)

Authors: Gay Talese

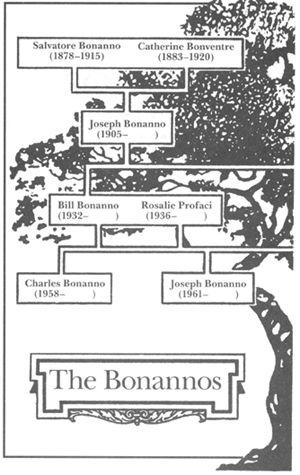

J | | Patriarch of family. Born in 1905 in western Sicilian town of Castellammare del Golfo. An anti-Fascist student radical in Palermo after Mussolini came to power in 1922, Bonanno fled Sicily and entered United States during Prohibition. Decades later, a millionaire, Bonanno was identified by U.S. government as one of top bosses in American Mafia. |

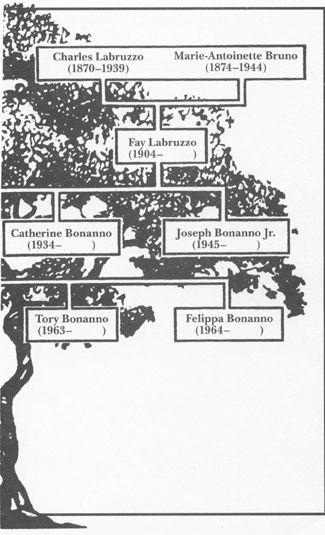

F | | Wife of Joseph Bonanno. Born Fay Labruzzo in Tunisia of Sicilian parents who later emigrated to United States and settled in Brooklyn. There, in 1931, she married Joseph Bonanno. |

S | | Eldest son of Joseph and Fay Bonanno, born 1932. |

C | | Daughter of Joseph and Fay Bonanno, born 1934. |

J | | Younger son of Joseph and Fay Bonanno, born 1945. |

R | | Wife of Bill Bonanno, whom she married in 1956. Born Rosalie Profaci in 1936; niece of Joseph Profaci. |

Joseph P | | Millionaire importer of olive oil and tomato paste. Until death from cancer in 1962, boss of Brooklyn organization with close ties to organization headed by Joseph Bonanno. Born Villabate, Sicily, 1897. |

J | | His sister married to Joseph Profaci; after Profaci’s death, Magliocco, a longtime aide, succeeded to leadership of Profaci organization. Suffered fatal heart attack in December 1963. |

J | | Succeeded Magliocco; negotiated uncertain peace within factionalized Profaci organization following Gallo brothers revolt of 1960, but organization never regained power it had during 1950s and 1940s under Profaci. Colombo in 1970 started Italian-American Civil Rights League; in 1971, at League outdoor rally, Colombo was shot by black man posing as photographer. |

S | | Boss in Buffalo area. Native of Castellammare del Golfo, distant cousin of Joseph Bonanno, but enemy of Bonanno since 1960s. |

G | | Magaddino’s brother-in-law, loyal member of Joseph Bonanno organization for years—until in 1964, disenchanted by elevation of thirty-two-year-old Bill Bonanno in organization, led internal revolt that led in mid-1960s to so-called Banana War. Magaddino, among others, backed Di Gregorio’s cause. |

F | | Brother of Fay Bonanno and loyal captain in Joseph Bonanno organization. |

J | | Loyal captain in Bonanno organization |

J | | Cousin of Joseph Bonanno and veteran officer in organization who in 1950s returned to native Sicily to retire. In 1971, in Italian government’s anti-Mafia drive, Bonventre was cited as leader and exiled with other alleged mafiosi to small island off northeast coast of Sicily. |

F | | Loyal Bonanno captain; returned to peaceful retirement in Sicily in 1950s, where he died natural death. |

P | | Bonanno member who quit organization in 1964 dispute, joined Di Gregorio’s faction. |

F | | Bonanno member who joined Di Gregorio and became identified as top triggerman against Bonanno loyalists during Banana War in mid-1960s. |

P | | First cousin of Stefano Magaddino, the boss in Buffalo; Peter Magaddino left Buffalo and supported Joseph Bonanno, his boyhood friend in Sicily, in the dispute with Di Gregorio’s faction. |

S | | Old-time Sicilian boss from Castellammare del Golfo; friend of Joseph Bonanno’s father. In 1930, Maranzano organized group of Castellammarese immigrants in Brooklyn to fight against New York organization headed by Joe Masseria, a southern Italian who wanted to eliminate Sicilian clan. This feud, extending from 1928 until 1931, became known as the Castellammarese War and is referred to in Chapter 12. |

T | | Called by several names—and never |

T | | Of the twenty-four bosses, nine take turns serving as members of the commission, which is dedicated to maintaining peace in the underworld; but it is supposed to restrain itself from interfering with the internal affairs of any one boss. Occasionally it cannot resist, and then—as with the Bonanno affair in the mid-1960s—there is trouble. Before the Bonanno affair, however, the commission members subordinated their differences and kept the nine-man membership in tact. The commission included the following: |

J | | New York |

J | | New York |

V | | Succeeded to leadership of New York-based organization once headed by Lucky Luciano, who, after being sentenced in 1936 to long prison term, was deported to Italy in 1946. Frank Costello, who tried to take over the Luciano organization, was discouraged when his skull was grazed with a bullet in 1957. |

T | | New York. Took over leadership of organization headed by Gaetano Gagliano, who died of natural causes in 1953. |

C | | New York. Close to Lucchese; their children intermarried. Gambino heads organization formerly controlled by Albert Anastasia, who was fatally shot in a Manhattan barbershop in 1957. |

S | | Buffalo. Born in 1891 in Castellammare del Golfo, he is senior member of commission. |

A | | Boss of organization centered in Philadelphia. |

S | | Boss of organization centered in Chicago. |

J | | Boss of organization in Detroit. |

O | | It is most often assumed by newspaper readers that the Mafia is all there is to organized crime in America, when in fact the Mafia is merely a small part of the organized crime industry. There are an estimated 5,000 mafiosi belonging to twenty-four “families”; but federal investigators estimate that there are more than 100,000 organized gangsters working full-time in the crime industry—engaged in numbers racketeering, bookmaking, loan-sharking, narcotics, prostitution, hijacking, enforcing, debt collecting, and other activities. These gangs, who may work in cooperation with Mafia gangs or may be entirely independent, are composed of Jews, Irish, blacks, Wasps, Latin Americans, and every ethnic or racial type in the nation. |

This book is a study of the rise and fall of the Bonanno organization, a personal history of ethnic progression and of dying traditions.

THE DISAPPEARANCE

K

NOWING THAT IT IS POSSIBLE TO SEE TOO MUCH, MOST

doormen in New York have developed an extraordinary sense of selective vision: they know what to see and what to ignore, when to be curious and when to be indolent; they are most often standing indoors, unaware, when there are accidents or arguments in front of their buildings; and they are usually in the street seeking taxicabs when burglars are escaping through the lobby. Although a doorman may disapprove of bribery and adultery, his back is invariably turned when the superintendent is handing money to the fire inspector or when a tenant whose wife is away escorts a young woman into the elevator—which is not to accuse the doorman of hypocrisy or cowardice but merely to suggest that his instinct for uninvolvement is very strong, and to speculate that doormen have perhaps learned through experience that nothing is to be gained by serving as a material witness to life’s unseemly sights or to the madness of the city. This being so, it was not surprising that on the night when the Mafia chief, Joseph Bonanno, was grabbed by two gunmen in front of a luxury apartment house on Park Avenue near Thirty-sixth Street, shortly after midnight on a rainy Tuesday in October, the doorman was standing in the lobby talking to the elevator man and saw nothing.

It had all happened with dramatic suddenness. Bonanno, returning from a restaurant, stepped out of a taxicab behind his lawyer, William P. Maloney, who ran ahead through the rain toward the canopy. Then the gunmen appeared from the darkness and began pulling Bonanno by the arms toward an awaiting automobile. Bonanno struggled to break free but he could not. He glared at the men, seeming enraged and stunned—not since Prohibition had he been so abruptly handled, and then it had been by the police when he had refused to answer questions; now he was being prodded by men from his own world, two burly men wearing black coats and hats, both about six feet tall, one of whom said: “Com’on, Joe, my boss wants to see you.”

Bonanno, a handsome gray-haired man of fifty-nine, said nothing. He had gone out this evening without bodyguards or a gun, and even if the avenue had been crowded with people he would not have called to them for help because he regarded this as a private affair. He tried to regain his composure, to think clearly as the men forced him along the sidewalk, his arms numb from their grip. He shivered from the cold rain and wind, feeling it seep through his gray silk suit, and he could see nothing through the mist of Park Avenue except the taillights of his taxicab disappearing uptown and could hear nothing but the heavy breathing of the men as they dragged him forward. Then, suddenly from the rear, Bonanno heard the running footsteps and voice of Maloney shouting: “Hey, what the hell’s going on?”

One gunman whirled around, warning, “Quit it, get back!”

“Get out of here,” Maloney replied, continuing to rush forward, a white-haired man of sixty waving his arms in the air, “that’s my client!”

A bullet from an automatic was fired at Maloney’s feet. The lawyer stopped, retreated, ducking finally into the entrance of his apartment building. The men shoved Bonanno into the back seat of a beige sedan that had been parked on the corner of Thirty-sixth Street, its motor idling. Bonanno lay on the floor, as he had been told, and the car bolted toward Lexington Avenue. Then the doorman joined Maloney on the sidewalk, arriving too late to see anything, and later the doorman claimed that he had not heard a shot.

Bill Bonanno, a tall, heavy, dark-haired man of thirty-one whose crew cut and button-down shirt suggested the college student that he had been in the 1950s but whose moustache had been grown recently to help conceal his identity, sat in a sparsely furnished apartment in Queens listening intently as the telephone rang. But he did not answer it.

It rang three times, stopped, rang again and stopped, rang a few more times and stopped. It was Labruzzo’s code. He was in a telephone booth signaling that he was on his way back to the apartment. On arriving at the apartment house, Labruzzo would repeat the signal on the downstairs doorbell and the younger Bonanno would then press the buzzer releasing the lock. Bonanno would then wait, gun in hand, looking through the peephole to be sure that it was Labruzzo getting out of the elevator. The furnished apartment the two men shared was on the top floor of a brick building in a middleclass neighborhood, and since their apartment door was at the end of the hall they could observe everyone who came and went from the single self-service elevator.

Such precautions were being taken not only by Bill Bonanno and Frank Labruzzo but by dozens of other members of the Joseph Bonanno organization who for the last few weeks had been hiding out in similar buildings in Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. It was a tense time for all of them. They knew that at any moment they could expect a confrontation with rival gangs trying to kill them or with government agents trying to arrest them and interrogate them about the rumors of violent plots and vendettas now circulating through the underworld. The government had recently concluded, largely from information obtained through wiretapping and electronic bugging devices, that even the top bosses in the Mafia were personally involved in this internal feud and that Joseph Bonanno, a powerful don for thirty years, was in the middle of the controversy. He was suspected by other dons of excessive ambition, of seeking to expand—at their expense and perhaps over their dead bodies—the influence that he already had in various parts of New York, Canada, and the Southwest. The recent elevation of his son, Bill, to the number three position in the Bonanno organization was also regarded with alarm and skepticism by a few leaders of other gangs as well as by some members of Bonanno’s own gang of about 300 men in Brooklyn.

The younger Bonanno was considered something of an eccentric in the underworld, a privileged product of prep schools and universities whose manner and methods, while not lacking in courage, conveyed some of the reckless spirit of a campus activist. He seemed impatient with the system, unimpressed with the roundabout ways and Old World finesse that are part of Mafia tradition. He said what was on his mind, not altering his tone when addressing a mafioso of superior rank and not losing his sense of youthful conviction even when speaking the dated Sicilian dialect he had learned as a boy from his grandfather in Brooklyn. The fact that he was six feet two and weighed more than 200 pounds and that his posture was erect and his mind very quick added to the formidability of his presence and lent substance to his own high opinion of himself, which was that he was the equal or superior of every man with whom he was associating except for possibly one, his father. When in the company of his father, Bill Bonanno seemed to lose some of his easy confidence and poise, becoming more quiet, hesitant, as if his father were severely testing his every word and thought. He seemed to exhibit toward his father a distance and formality, taking no more liberties than he would with a stranger. But he was also attentative to his father’s needs and seemed to take great pleasure in pleasing him. It was obvious that he was awed by his father, and while he no doubt had feared him and perhaps still did, he also worshiped him.

During the last few weeks he had never been far from Joseph Bonanno’s side, but last night, knowing that his father wished to dine alone with his lawyers and that he planned to spend the evening at Maloney’s place, Bill Bonanno passed a quiet evening at the apartment with Labruzzo, watching television, reading the newspapers, and waiting for word. Without knowing exactly why, he was mildly on edge. Perhaps one reason was a story he had read in

The Daily News

reporting that life in the underworld was becoming increasingly perilous and claiming that the elder Bonanno had recently planned the murder of two rival dons, Carlo Gambino and Thomas (Three-Finger Brown) Lucchese, a scheme that supposedly failed because one of the triggermen had betrayed Bonanno and had tipped off one of the intended victims. Even if such a report were pure fabrication, based possibly on the FBI’s wiretapping of low-level Mafia gossip, the younger Bonanno was concerned about the publicity given to it because he knew that it could intensify the suspicion which did exist among the various gangs that ran the rackets (which included numbers games, bookmaking, loan-sharking, prostitution, smuggling, and enforced protection). The publicity could also inspire the outcry of the politicians, provoke the more vigilant pursuit of the police, and result in more subpoenas from the courts.

The subpoena was dreaded in the underworld now more than before because of a new federal law requiring that a suspected criminal, if picked up for questioning, must either testify if given immunity by the court or face a sentence for contempt. This made it imperative for the men of the Mafia to remain inconspicuous if they wanted to avoid subpoenas every time there were newspaper headlines. The law also impeded the Mafia leaders’ direction of their men in the street because their men, having to be very cautious and often detained by their caution and evasiveness, were not always where they were supposed to beat the appointed hour to do a job, and frequently they were unavailable to receive, at designated telephone booths at specific moments, prearranged calls from headquarters seeking a report on what had happened. In a secret society where precision was important, the new problem in communications was grating the already jangled nerves of many top mafiosi.

The Bonanno organization, more progressive than most partly because of the modern business methods introduced by the younger Bonanno, had solved its communications problem to a degree by its bell-code system and also by the use of a telephone answering service. It was perhaps the only gang in the Mafia with an answering service. The service was registered in the name of a fictitious Mr. Baxter, which was the younger Bonanno’s code name, and it was attached to the home telephone of one member’s maiden aunt who barely spoke English and was hard of hearing. Throughout the day various key men would call the service and identify themselves through agreed-upon aliases and would leave cryptic messages confirming their safety and the fact that business was progressing as usual. If a message contained the initials “IBM”—“suggest you buy more IBM”—it meant that Frank Labruzzo, who had once worked for IBM, was reporting. If the word “monk” was in a message, it identified another member of the organization, a man with a tonsured head who often concealed his identity in public under a friar’s robe. Any reference to a “salesman” indicated the identity of one of the Bonanno captains who was a jewelry salesman on the side; and “flower” alluded to a gunman whose father in Sicily was a florist. A “Mr. Boyd” was a member whose mother was known to live on Boyd Street in Long Island, and reference to a “cigar” identified a certain lieutenant who was never without one. Joseph Bonanno was known on the answering service as “Mr. Shepherd.”

One of the reasons that Frank Labruzzo had left the apartment that he shared with Bill Bonanno was to telephone the service from a neighborhood coin box and also to buy the early edition of the afternoon newspapers to see if there were any developments of special interest. As usual, Labruzzo was accompanied by the pet dog that shared their apartment. It had been Bill Bonanno who had suggested that all gang members in hiding keep dogs in their apartments, and while this had initially made it more difficult for the men to find rooms, since some landlords objected to pets, the men later agreed with Bonanno that a dog made them more alert to sounds outside their doors and also was a useful companion when going outside for a walk—a man with a dog aroused little suspicion in the street.

Bonanno and Labruzzo happened to like dogs, which was one of the many things that they had in common, and it contributed to their compatibility in the small apartment. Frank Labruzzo was a calm, easygoing, somewhat stocky man of fifty-three with glasses and graying dark hair; he was a senior officer in the Bonanno organization and also a member of the immediate family—Labruzzo’s sister, Fay, was Joseph Bonanno’s wife and Bill Bonanno’s mother, and Labruzzo was close to the son in ways that the father was not. There was no strain or stress between these two, no competitiveness or problems of vanity and ego. Labruzzo, not terribly ambitious for himself, not driven like Joseph Bonanno or restless like the son, was content with his secondary position in the world, recognizing the world as a much larger place than either of the Bonannos seemed to think it was.

Labruzzo had attended college, and he had engaged in a number of occupations but had pursued none for very long. He had, in addition to working for IBM, operated a dry-goods store, sold insurance, and had been a mortician. Once he owned, in partnership with Joseph Bonanno, a funeral parlor in Brooklyn near the block of his birth in the center of a neighborhood where thousands of immigrant Sicilians had settled at the turn of the century. It was in this neighborhood that the elder Bonanno courted Fay Labruzzo, daughter of a prosperous butcher who manufactured wine during Prohibition. The butcher was proud to have Bonanno as a son-in-law even though the wedding date, in 1930, had to be postponed for thirteen months due to a gangland war involving hundreds of newly arrived Sicilians and Italians, including Bonanno, who were continuing the provincial discord transplanted to America but originating in the ancient mountain villages that they had abandoned in all but spirit. These men brought to the New World their old feuds and customs, their traditional friendships and fears and suspicions, and they not only consumed themselves with these things but they also influenced many of their children and sometimes their children’s children—among the inheritors were such men as Frank Labruzzo and Bill Bonanno, who now, in the mid-1960s, in an age of space and rockets, were fighting a feudal war.

It seemed both absurd and remarkable to the two men that they had never escaped the insular ways of their parents’ world, a subject that they had often discussed during their many hours of confinement, discussing it usually in tones of amusement and unconcern, although with regret at times, even bitterness.

Yes, we’re in the wagon wheel business

, Bonanno had once sighed, and Labruzzo had agreed—they were modern men, lost in time, grinding old axes. This fact was particularly surprising in the case of Bill Bonanno: he left Brooklyn at an early age to attend boarding schools in Arizona, where he was reared outside the family, learned to ride horses and brand cattle, dated blonde girls whose fathers owned ranches; and later, as a student at the University of Arizona, he led a platoon of ROTC cadets across the football field before each game to help raise the American flag before the national anthem was played. That he could have suddenly shifted from this campus scene in the Southwest to the precarious world of his father in New York was due to a series of bizarre circumstances that were perhaps beyond his control, perhaps not. Certainly his marriage was a step in his father’s direction, a marriage in 1956 to Rosalie Profaci, the pretty dark-eyed niece of Joseph Profaci, the millionaire importer who was also a member of the Mafia’s national commission.