Honor Among Thieves

Honor Among Thieves

The Ancient Blades Trilogy: Book Three

David Chandler

For J.R.R.T. and G.R.R.M., the Epic Overlords

T

he Free City of Ness was known around the world as a hotbed of thievery, and one man alone was responsible for that reputation. Cutbill, master of that city’s guild of thieves, controlled almost every aspect of clandestine commerce within its walls—from extortion to pickpocketing, from blackmail to shoplifting, he oversaw a great empire of crime. His fingers were in far more pies than anyone even realized, and his ambitions far greater than simple acquisition of wealth—and far broader-reaching than the affairs of just one city. His interests lay in every corner of the globe and his spies were everywhere.

As a result he received a fair volume of mail every day.

In his office under the streets of Ness, he went through this pile of correspondence with the aid of only one assistant. Lockjaw, an elderly thief with a legendary reputation, was always there when Cutbill opened his letters. There were two reasons why Lockjaw held this privileged responsibility—for one, Lockjaw was famous for his discretion. He’d received his sobriquet for the fact that he never revealed a secret. The other reason was that he never learned to read.

It was Lockjaw’s duty to receive the correspondence, usually from messengers who stuck around only long enough to get paid, and to comment on each message as Cutbill told him its contents. If Lockjaw wondered why such a clever man wanted his untutored opinion, he never asked.

“Interesting,” Cutbill said, holding a piece of parchment up to the light. “This is from the dwarven kingdom. It seems they’ve invented a new machine up there. Some kind of winepress that churns out books instead of vintage.”

The old thief scowled. “That right? Do they come out soaking wet?”

“I imagine that would be a defect in the process,” Cutbill agreed. “Still. If it works, it could produce books at a fraction of the cost a copyist charges now.”

“Bad news, then,” Lockjaw said.

“Oh?”

“Books is expensive,” the thief explained. “There’s good money in stealing ’em. If they go cheap all of a sudden we’d be out of a profitable racket.”

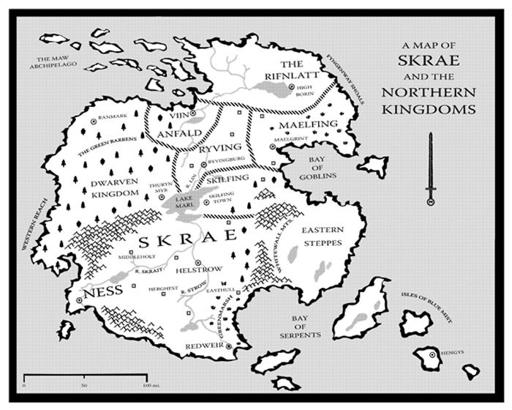

Cutbill nodded and put the letter aside, taking up another. “It’ll probably come to nothing, this book press.” He slit open the letter in his hand with a knife and scanned its contents. “News from our friend in the north. It looks like Maelfing will be at war with Skilfing by next summer. Over fishing rights, of course.”

“That lot in the Northern Kingdoms is always fighting about something,” Lockjaw pointed out. “You’d figure they’d have sorted everything out by now.”

“The king of Skrae certainly hopes they never do,” Cutbill told him. “As long as they keep at each other’s throats, our northern border will remain secure. Pass me that packet, will you?”

The letter in question was written on a scroll of vellum wrapped in thin leather. Cutbill broke its seal and spread it out across his desk, peering at it from only a few inches away. “This is from our man in the high pass of the Whitewall Mountains.”

“What could possibly happen in a desolated place like that?” Lockjaw asked.

“Nothing, nothing at all,” Cutbill said. He looked up at the thief. “I pay my man there to make sure it stays that way.” He read some more, and opened his mouth to make another comment—and then closed it again, his teeth clicking together. “Oh,” he said.

Lockjaw held his peace and waited to hear what Cutbill had found.

The master of the guild of thieves, however, was unforthcoming. He rolled the scroll back up and shoved the whole thing in a charcoal brazier used to keep the office warm. Soon the scroll had caught flame, and in a moment it was nothing but ashes.

Lockjaw raised an eyebrow but said nothing.

Whatever was on that scroll clearly wasn’t meant to be shared, even with Cutbill’s most trusted associate. Which meant it had to be pretty important, Lockjaw figured. More so than who was stealing from whom or where the bodies were buried.

Cutbill went over to his ledger—the master account of all his dealings, and one of the most secret books on the continent. It contained every detail of all the crime that took place in Ness, as well as many things no one had ever heard of outside of this room. He opened it to a page near the back, then laid his knife across one of the pages, perhaps to keep it from fluttering out of place. Lockjaw noticed that this page was different from the others. Those were filled with columns of neat figures, endless rows of numbers. This page only held a single block of text, like a short message.

“Old man,” Cutbill said then, “could you do me a favor and pour me a cup of wine? My throat feels suddenly raw.”

Cutbill had never asked for such a thing before. The man had enough enemies in the world that he made a point of always pouring his own wine—or having someone taste it before him. Lockjaw wondered what had changed, but he shrugged and did as he was told. He was getting paid for his time. He went to a table over by the door and poured a generous cup, then turned around again to hand it to his boss.

Except Cutbill wasn’t there anymore.

That in itself wasn’t so surprising. There were dozens of secret passages in Cutbill’s lair, and only the guildmaster knew them all or where they led. Nor was it surprising that Cutbill would leave the room so abruptly. Cautious to a nicety, he always kept his movements secret.

No, what was surprising was that he didn’t come back.

He had effectively vanished from the face of the world.

Day after day Lockjaw—and the rest of Ness’s thieves—waited for his return. No sign of him was found, nor any message received. Cutbill’s operation began to falter in his absence—thieves stopped paying their dues to the guild, citizens under Cutbill’s protection were suddenly vulnerable to theft, what coin did come in piled up uncounted and was spent on frivolous expenditures. Half of these excesses were committed in the belief that Cutbill, who had always run a tight ship, would be so offended he would have to come back just to put things in order.

But Cutbill left no trace, wherever he’d traveled.

It was quite a while before anyone thought to check the ledger, and the message Cutbill had so carefully marked.