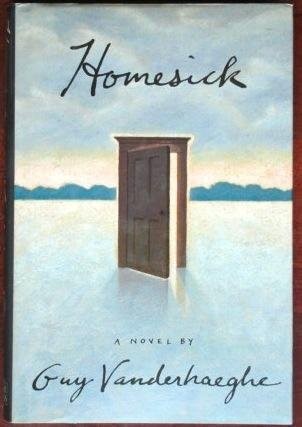

Homesick

ACCLAIM FOR

Homesick

“One has only to read the first page of Guy Vanderhaeghe’s

Homesick

to see why his books have garnered him international awards.…”

–

Regina Leader-Post

“If great art is that which holds a mirror up to nature, as was once said, then

Homesick

is great art.”

–

Daily News

(Halifax)

“[Vanderhaeghe’s characters] lift themselves by pride and love from the ordinariness of their world.”

–

Ottawa Citizen

“Vanderhaeghe has an unerring eye for the prairie landscape and a shrewd ear for the ironies of small-town conversation.… He balances his dramatization of the cycle of life with exuberant storytelling.…”

–

London Free Press

“His stories and novels are character studies par excellence.…”

– Andreas Schroeder

“Guy Vanderhaeghe writes about what he knows best: people, their sense of mortality, their difficulty in being good during a difficult time.… The dialogue and the characters are eclectic and real.”

–

Vancouver Sun

“Beautifully written … Vanderhaeghe writes in a spare, poetic prose that is deceptively simple. He uses his medium very effectively to capture both the icy harshness and the warmth of family life.…

Homesick

is an unexpectedly powerful work.… His extraordinary talents deserve wide recognition.”

–

Whig-Standard

(Kingston)

BOOKS BY GUY VANDERHAEGHE

NOVELS

My Present Age

(1984)

Homesick

(1989)

The Englishman’s Boy

(1996)

SHORT STORIES

Man Descending

(1982)

The Trouble With Heroes

(1983)

Things As They Are?

(1992)

PLAYS

I Had a Job I Liked. Once

. (1992)

Dancock’s Dance

(1996)

Copyright © 1989 by Guy Vanderhaeghe

Cloth edition published 1989

This trade paperback edition published 1999

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher – or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency – is an infringement of the copyright law.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Vanderhaeghe, Guy, 1951-

Homesick

eISBN: 978-1-55199-567-0

I. Title.

PS8593.A5386H6 1999 C813′.54 C98-932930-5

PR9199.3.V36H6 1999

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program for our publishing activities. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart Inc.

The Canadian Publishers

75 Sherbourne Street,

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P9

v3.1

To Margaret, as always

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the Canada Council and the Saskatchewan Arts Board for their generous financial assistance during the writing of

Homesick

.

I would also like to express my thanks to my editor Ellen Seligman for her careful and thoughtful labours.

Portions of this novel have previously appeared in the following: a slightly altered version of Chapter 1 was read on CBC Radio’s “Speaking Volumes” and “Aircraft”; Chapter 3 previously appeared in

Books in Canada

.

Contents

1

A

n old man lay asleep in his bed. This was his dream:

He is young again, once more an ice-cutter laying up a store of ice for the summer. The Feinrich brothers and he drive their sledges out on to the wide white plain of the lake. The runners hiss on the dry snow, metal bits in the harness shift and clink, leather reins freeze so hard they lie stiff and straight as laths down the horses’ backs. Before them the sky lightens over purple-shadowed, hunch-shouldered hills.

When the sun finally rises, so does the wind, bitter and cutting. On the lake there is no place to escape it, no trees, no sheds, no bluffs to hunker down and hide behind. On the lake there is only flatness, a rushing space that squeezes eyes into a squint.

There it is now, the first long drawn-out sigh of breath tumbling over the hills, the faint breeze setting snow snakes writhing out over the ice and hard-packed drifts to meet them. By fits and starts this wind gathers force, the skirts of coats billow and snap, its fierce touch penetrates every layer of clothing, drives nails of cold through coveralls, trousers, woollen combinations. It raises

gooseflesh and tears the manes of the horses into ragged, whipping flags. It pounds the drum-skins of tightly drawn parka hoods.

They halt. The horses stamp on wind-polished ice. Down from the sledge, standing on bare, clean ice he can feel the cold rise through the soles of his boots, seep through stockings, sting toes. Walking over the ice he can sense the yaw and pitch, the tilt, the gentle undulations that cannot be seen but must be felt, things the eye skates over, fails to register. It makes him feel uneasy, unsteady. He thinks of the waves which ran one after another in slow succession to shore until winter laid its dead hand upon their backs, binding up the heaves and swells, arresting motion. He sees the long rivers of fracture, the widely flung tributary cracks.

He chops a hole for the saw. The axe makes a terrible ringing on the ice, a clash like metal striking metal. With each blow, shards of ice leap like sparks in the air. He opens the lake for the ice-cutters, water spurts and gurgles in the wound. By the time he raises the axe above his head, the water splashed on the blade freezes in a glassy sheath.

The saws squeak. The first block is lifted dripping and gleaming. A square of black water opens wide at his feet. His feet are numb with cold.

So he dances. Dances to heat his feet. A polka right there on the huge ballroom floor of the lake, an imaginary partner cradled in the curve of his arm as he whirls round and round, boots clattering and heels flicking, the Feinrichs laughing and clapping time with their cow-hide mitts. Faster and faster he goes. The horses’ nostrils smoke surprise, their eyes roll, their heads jerk as he flashes by. Faster, faster. He throws back his head and sees the last faint stars, the pale silver moon spin with him. Dance with him.

Then he falls. A sudden stunning breath-robbing descent through searing cold and blackness. It blots away moon and stars. A slow, buoyant, bubbling rise which ends with a bump under the ice.

He stares up. Ice. He is under the ice, groping and scrabbling with his nails, searching for the cut-hole, a way out. He snuffles and

gulps the thin scraps of air captured between ice and water, kicks his legs frantically. He butts his head madly, desperately against the ice. Water rolls and churns over his shoulders. Out, out, out.

At last, exhausted, he can only hang in the water, suspended in silence and cold. His boots are buckets, pulling heavy on his ankles. His trouser legs balloon with cold and water. It is a silence like he has never heard, a cold like he has never felt. He grows colder by the second and guesses this means he is dying. This is a different kind of cold under the ice, you don’t go numb with it. The colder you get, the more it hurts. The more you die, the more you feel.

Every inch of him aches with it. He is cold through to the sap and marrow of his bones. The quiet is no less terrible.

Then he hears something. Above him, people walk. Crunch, creak go the footsteps.

“I’m down here!” he shouts. “I’m down here!”

They don’t heed his cry. They don’t stop. They pass over.

“For the love of God!” he shouts. “I’m down here! Under the ice!”

The crunch, creak fades away.

His last struggle against the ice begins. It is all rage and foaming water.

Alec Monkman woke in his bed, pillowcase bunched in an arthritic fist. Despite the violence of his grip, the ache and throb of skewed and swollen knuckles was lost beneath all the rest of it. Yet the pain was there, lurking deeper than bone, deep as the deepest waters of sleep from which he had fought upward in terror, cold and shivering, only to find more ice.

Monkman kept his eyes fixed on the feeble, milky light across the bedroom; stars hedged round by a window-frame. Underneath the ice he had sought for some sign of light, a glimmer to guide him.

Jesus Christ Almighty, maybe one of these nights he will drown and it will be left to Stutz to discover him in the morning, deader than Joe Cunt’s dog.

He had never had any affection for water. Strange then that his first job should have been building bridges. Not that he had had any choice; his Dad had got him the job. His father had work on a bridge construction crew and got him a place by lying about his age. He was fourteen. It was his father’s opinion that children ought not to get accustomed to living off their parents’ charity, and that fourteen was just about the proper weaning age. So Alec had been put to work driving a gravel wagon two months after the decisive birthday.

Sitting on the seat of that wagon he had seen his first man killed. He had glanced up and seen the half-breed fall from a trestle, sixty feet down to the river. The breed had looked like a spider dropping on a spinner, arms and legs splayed out and working like crazy. The men said he knocked himself out because of the way he fell, face down and on his belly. It kicked the air out of his lungs and did him in, stole any chance of survival he had. Nobody could reach him out in the river, the race of water was too strong, sweeping him around the bend and out of sight before anyone could move.

They had unhitched Alec’s team and he and three others had chased down the river after him on the horses, only catching up when the body hooked on a snag. They found him with the white water tumbling over his shoulders and his long black Indian hair fanned out from his skull, rippling and waving in the current.

He had never forgotten how water swallowed you. Never completely trusted it, even when it was eighteen inches thick and solid. One winter was all he could bring himself to cut ice.

Stutz knew about the dream. He had asked Stutz what he made of it. “It’s the arthritis,” said Stutz. “It makes you ache in your sleep and you dream the cold.”

The dream, or a variation on it, visited Monkman every week or so. Sometimes when he floated upright in the icy water, the life trickling out of him, it wasn’t footsteps he heard above him but singing far off in the distance, the faded harmony of childish voices. Other times the ice was absolutely clear, a pane of glass,

and he could stare up through it at the sky, the moon, the stars.

No one dream was any easier to bear than another.

He shifted his eyes from the window to the clock. A bit past one o’clock. Not so very late.

Monkman climbed out of bed, pulled on a pair of socks, padded downstairs in his underwear. He could not help himself. He needed the sound of another voice to break the loneliness of the ice. Before he had even prepared his excuse for calling, he had dialled Stutz’s number and the phone was ringing. It rang nine times and then Stutz answered.

“Yes, Alec?” Stutz knew who would be the only person phoning at that hour.

Monkman cast desperately around in his mind, scrambling for a plausible reason for disturbing him.

“Yes, Alec?” repeated Stutz patiently.

Monkman seized upon the first thing which offered itself. “You know Vera and her boy are coming tomorrow. Can you pick them up?”

“Is that the bus?”