Home Team

Authors: Sean Payton

Table of Contents

New American Library

Published by New American Library, a division of

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2,

Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124,

Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Published by New American Library, a division of

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2,

Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124,

Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by New American Library,

a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First Printing, July 2010

All rights reserved

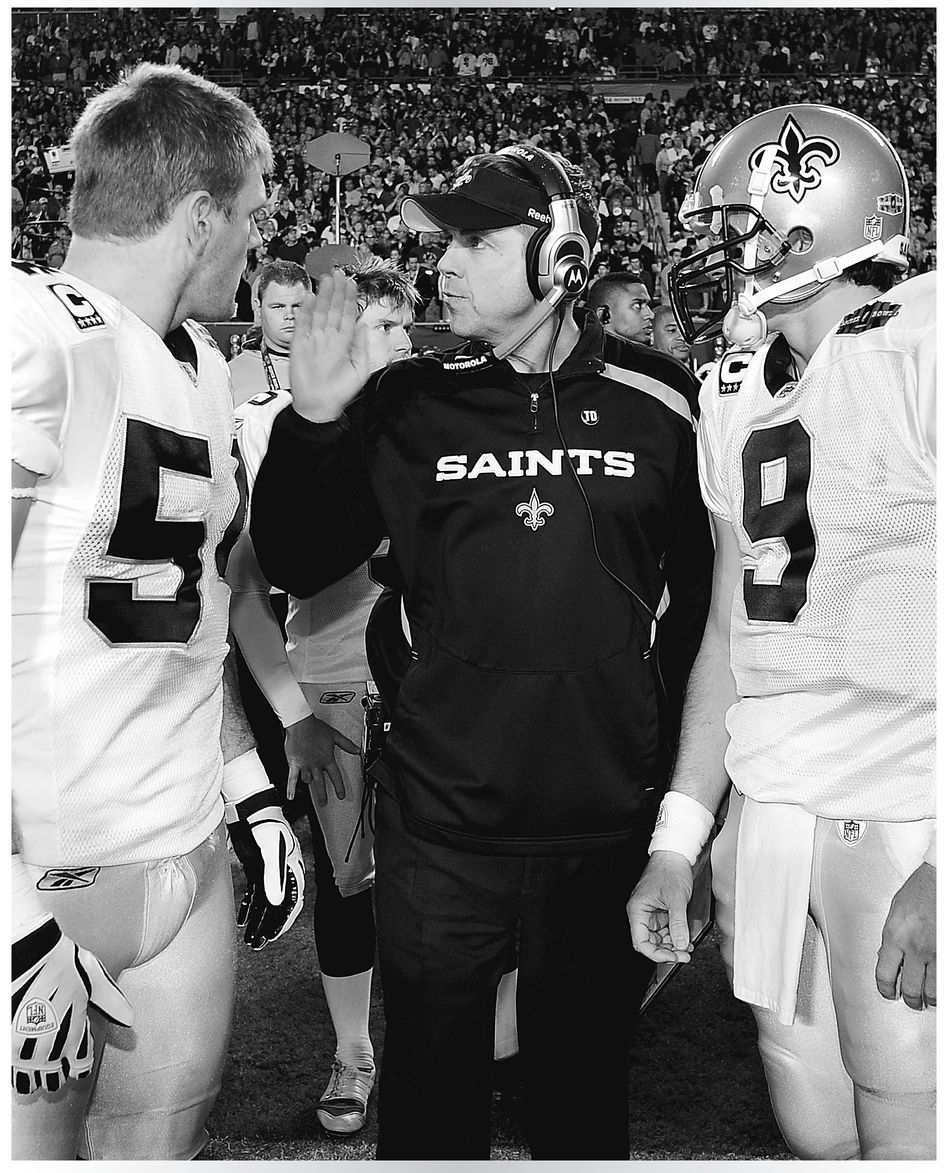

Insert and text photos used wth permission of the New Orleans Saints; copyright © New Orleans

Louisiana Saints; photos taken by Michael C. Hebert.

Louisiana Saints; photos taken by Michael C. Hebert.

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADALIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA:

Payton, Sean.

Home team: coaching the Saints and New Orleans back to life/Sean Payton and Ellis Henican.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-101-44217-3

1. Payton, Sean. 2. Football coaches—United States—Biography. 3. New Orleans Saints (Football team) 4. Football—Social aspects—Louisiana—New Orleans. 5. Hurricane Katrina, 2005. I. Henican, Ellis. II. Title.

GV939.P388A3 2010

796.332’640976335—dc22

2010013731

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For those who came while others were leaving:

Beth, Meghan and Connor,

the coaches, players and staff of the New Orleans Saints

and all the brave and generous souls

who’ve helped to revive

New Orleans and the Gulf Coast—

my home team

Beth, Meghan and Connor,

the coaches, players and staff of the New Orleans Saints

and all the brave and generous souls

who’ve helped to revive

New Orleans and the Gulf Coast—

my home team

INTRODUCTION

WHEN THEY REALLY LOVE

you in New Orleans, they have their own unique ways of saying so. If a great trumpet player dies, people don’t get all mournful. They dance in the streets with brightly colored umbrellas, then slide the dearly departed into a concrete tomb a couple of feet off the ground.

you in New Orleans, they have their own unique ways of saying so. If a great trumpet player dies, people don’t get all mournful. They dance in the streets with brightly colored umbrellas, then slide the dearly departed into a concrete tomb a couple of feet off the ground.

Well, I’m not ready for my own jazz funeral. Not yet. But I’m pretty sure I have now experienced the next-best thing: riding down St. Charles Avenue on a giant Mardi Gras float, parading with a bunch of guys I love and admire and some of the hottest brass bands on Earth while hundreds of thousands of appreciative people yell, clap, cheer, wave signs, weep openly and call out our names.

They were cheering for their team.

They were cheering for their city.

They were cheering for themselves.

And we were cheering right back at them.

How many people turned out for the New Orleans Saints Super Bowl Victory Parade? Nobody knows for certain. Attendance isn’t taken at Mardi Gras parades. Eight hundred thousand? The media estimates went as high as a million. Either way, that’s really saying something in a city whose official population is in the mid-300,000s, down a quarter since Hurricane Katrina, a metro area of a million and low change. Basically, nobody stayed home.

I know what I saw from my float as we inched through the crowds: men, women and children, fifteen and twenty deep, a swirling sea of black and gold along the entire 3.7-mile route from the Louisiana Superdome through the Central Business District, out and back down Canal Street, to Mardi Gras World on the Mississippi River.

“Thank you!” they screamed.

“We’re back, baby!”

“New Aaaaw-lins!”

New Orleans may not be the swiftest when it comes to amassing Super Bowl victories. But let me tell you: This city knows how to throw a parade. It was hard to imagine anything like this in any other city, this category 5 outpouring of gratitude and love. Babies in tiny Saints hats, giggling and waving. Grown women shouting the universal Saints hello: “Who dat? Who dat?” Burly men hugging one another. Kids rushing up for autographs. One old man in a Deuce McAllister jersey was standing by a blue police barricade on Howard Avenue, tears running down his face. Three Catholic nuns at Canal and Baronne were so ecstatic they were jumping up and down.

These were the people we’d been playing for—people who’d lost so much and struggled so valiantly, literally crying tears of joy. They’d lived though unthinkable hardship: losing their homes, being scattered across the country, some of them seeing their relatives drown. They came from every neighborhood and every background. Relative newcomers and people whose families have been in Louisiana for centuries. Black people. White people. People in such elaborate costumes, you couldn’t tell who they were. All of them were united in triumph now.

Many had brought signs from home. These weren’t preprinted placards. These were handwritten sentiments, direct and personal. “Bless you, Boys!!” “Only yo mama loves you more than we do!” “Our City, Victims to Victors.” “Baylen Brees, will you marry me?” Baylen is Drew’s baby son.

These were the people Jimmy Buffett was talking about when he called New Orleans “the soul of our country.” They have been so kind to us. I truly have come to treasure them.

The people of this region lived through the most devastating natural disaster in American history. Eighty percent of their city was flooded when the levees broke. They’d lost their jobs. People they’d known, people they loved had been forced to leave and weren’t coming back. Government had failed them at every level. The media had grown bored and moved on. And yet these people still had not lost their will to celebrate. Their spirit made me care deeply about a place I had barely known before. Their courage inspired a struggling football team all the way to the Super Bowl.

And here they were, standing shoulder to shoulder on this raw New Orleans night. Everything in New Orleans gets a name in a hurry. This was either Dat Tuesday or Lombardi Gras. Clearly, we were all locked together, city and team.

Reggie Bush looked totally Hollywood in dark sunglasses and a thousand-watt grin, throwing black-and-gold Saints beads and stuffed minifootballs from the running backs’ float. He and Pierre Thomas shared a microphone—and some impromptu raps for the crowd. Tough-guy tight end Jeremy Shockey turned suddenly bashful as people started chanting his name. Darren Sharper, Tracy Porter and others from the secondary rode a float with a pirate theme. That seemed right, given how often they ended up stealing the other team’s ball. Thomas Morstead and Garrett Hartley—our young punter and young kicker, whose combined ages added up to mine—rode on a float borrowed from the all-female Krewe of Muses. Appropriately, it featured a giant shoe. Garrett kept jumping off the float, hugging and high-fiving the people he passed.

Other books

Lord of the Blade by Elizabeth Rose

With Cruel Intent by Larsen, Dennis

How to Handle a Heartbreaker by Marie Harte

Eye of the Storms (Eye of the Storms #1) by Lisa Gillis

Velva Jean Learns to Fly by Jennifer Niven

JUSTICE Is SERVED (Food Truck 7) by Chloe Kendrick

David Bishop - Matt Kile 04 - Find My Little Sister by David Bishop

Sweet Victory by Sheryl Berk

Book 1 - The Man With the Golden Torc by Simon R. Green

Cowboy After Dark by Vicki Lewis Thompson