Hockey Confidential (36 page)

Read Hockey Confidential Online

Authors: Bob McKenzie

“We knew that day was special to him, and we were flattered he wanted to spend it with us, on the ice,” Stamkos said of the 08/08/08 session. “We all knew [after Ania's death] that Jari was hurting, that he was going through a difficult time, but I don't think anyone knew how bad it was. It was great to see him back doing what he loves.”

It wasn't lost on Byrski that he did, on what would have been his wedding day, something Ania likely would have objected to.

“I'm a workaholic, nonstop, that's who I am,” he said. “I've had some regrets about that, but I have to be content and live with my decisions. I wasn't able to balance my passion for work and my personal time. I should have been spending more time with Ania and my own kids, but at the end of the day, my passion was to love hundreds of kids but maybe not spend enough time with my wife and own family. . . . My professional life and my passion for it kind of burned everything around it.”

It's funny, though, how things work out.

In the early months of 2008, after Byrski came out of his deep, dark depression and was in the midst of rebuilding a business that, outside of his pro clientele, had largely fallen apart, he was having lunch with his sons, Matthew and Bart, talking about hiring a new secretary to get things up and running again.

“Matthew said to me that day, âWhy don't I try to help you?' So Matthew comes in, and next to Ania, he's the best person I've ever had in that job. And I said to him, âYou're a great skater, you know how I teach skating. You should be on the ice with me.'”

So SK8ON once again became a thriving enterprise, with much of the load being shouldered by Matthew Byrski, on the ice pretty much all day long and overseeing much of the company's administration.

“It's an incredible circle of life,” Byrski said of working and spending so much time with his eldest son. “Matthew is doing a great job of running the business, and I'll always want to be involved in some way. You know, a lot of the parents ask, âIs Jari going to be on the ice with my child?' so I'll still come on the ice for a few hours each day and be the crazy old man. I'll sing, be my Crazy Jari self, and they're happy, but I can't tell you what it means to be father and son working together and for Matthew to one day take over the business.”

Byrski knows times have changed. The kids all still come to learn, but it's not the same as it was for that decade, framed by Spezza and the 1983 birth year at one end and Jeff Skinner and the 1992 birth year at the other, when Jari developed special bonds with kids like Spezza, Burns, Wolski, Bickell, Stamkos, Del Zotto and Skinner, amongst others.

“The elite kids now, there's no time for extra skating and skills,” Byrski said. “AAA teams do it as a team. The coaches who get hired to coach these teams do it themselves or have someone to do it. Some kids would like private instruction, but they just don't have the time. I still love working with children, having fun, teaching them, but it'll never be like it was with Jason [Spezza] or Brent [Burns] or Wojtek [Wolski] or Steven [Stamkos].”

Byrski cherishes those relationships, looks fondly at the wall in his SK8ON office (in his condo) at all the signed photographs and many autographed jerseys from his NHL “boys.”

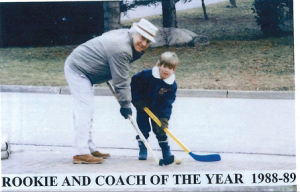

“It's very touching to me,” Byrski said. “I stepped on the ice in Canada for the first time in 1988, and this is the country that gave birth to hockey. It gave birth to Jean Beliveau and Rocket Richard and Gordie Howe and Bobby Orr and Wayne Gretzky and Mario Lemieux . . . This country is like a church, a holy land of hockey, and for me, a young boy from Poland with Ukrainian roots, to come here and start SK8ON and wear my blue and yellow, to expose my creativity and ability to everyone and be so scrutinized by people who know so much about hockey . . . and to develop the relationships I have with so many who have gone on to be stars in the NHL, I am blessed.”

But Jari Byrski won't soon forget the darkness and despair of Ania's passing, or the guilt he carried for allowing his professional life to overwhelm his personal life. He deals with that every day, and probably always will.

“I'm slowly making peace with myself on that,” he said.

When he's not on the ice at the rink, or working in his home office on SK8ON business, Jari has his paintings, his artwork. His living room looks like an art studio. Many pieces hang on the walls; others are in various states of completion on the floor of his condo. Most of them are impressionistic, abstract.

One of the pieces, hanging on the wall, is special. It's the T-shirt Ania was wearing when she died. It's been laid flat, stretched over a frame and painted over in a multitude of colours, pieces of broken glass incorporated for what Jari calls the “life experience,” as well as imagery of her heart, her veins. There are others pieces, too, lovely and colourful abstracts with layers of texture and intrigue, not unlike the man who paints them. He'll often paint one and give it to an NHL client who's getting married or having a baby, his art work on the front, an inscription or meaningful poem on the back, similar to the one he gave Stamkos in 2008, the one that in no small measure helped to save his own life.

“These pieces of art,” Jari Byrski said, “I call them by a title. I call them âThe Joy of Life.'”

Colin Campbell looks at the frozen pond that almost claimed his life when his tractor fell through the ice.

Bob McKenzie

A proud father: Campbell celebrates son Gregory's Stanley Cup victory with the Boston Bruins.

Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

A 17-year-old John Tavares celebrates Buffalo's 2008 NLL championship with his namesake uncle, lacrosse player John Tavares, and cousin Justin (centre).

Courtesy of Barb Tavares

Born to score goals: Young John Tavares always felt like he wanted it more than anyone else.

Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

Although Don Cherry and his son, Tim, will sit in the seats to watch minor midget hockey, they prefer to stand at the glass in the corner.

Lucas Oleniuk/Getty Images

It's not a Fifty-Mission Cap, but Gord Downie of the Tragically Hip understands what it's like to be at the Lonely End of the Rink.

David Bastedo

Even as a little guy playing for the York-Simcoe Express, Connor McDavid was exceptional.

Courtesy of the McDavid family

No one has had a bigger impact on McDavid's hockey life than his dad, Brian, who coached his son throughout much of his minor hockey career.

Courtesy of the McDavid family

McDavid got a surprise during a February 2013 visit to a Penguins game in Pittsburgh: a photo with heroes Mario Lemieux and Sidney Crosby.

© Pittsburgh Penguins

Whether he was playing street hockey as a little kid or playing junior in London, Brandon Prust always had his Granda Jimmy McQuillan in his corner.

Courtesy of the Prust Family

Getting a broken jaw, courtesy of Cam Janssen in December of 2008, was one of the worst events of Prust's life, but not so bad he couldn't take a selfie.

Courtesy of the Prust Family

Prust doesn't possess the physical dimensions of an NHL heavyweight, but that doesn't mean he won't drop the gloves with one, even Boston behemoth Milan Lucic.

Christopher Pasatieri/Getty Images

A 12-year-old Karl Subban, his mom, Fay, and younger brothers Markel (far left) and Patrick (far right) marvel at snow in the family's first Canadian winter in Sudbury.

Courtesy of Karl Subban