Hitching Rides with Buddha: A Journey Across Japan (12 page)

Read Hitching Rides with Buddha: A Journey Across Japan Online

Authors: Will Ferguson

I met him once. True story. It was in Fukuoka City during the Spring Tournament. He was retired then; his topknot had been ceremonially cut off the season before (I

cried

when I watched it on television) and he was now a senior statesman of sumo. I was up the night before and was wandering around Fukuoka’s notorious red-light district when lo! I ran right into Chiyonofuji. He was coming out of an exclusive all-girl topless cabaret. I recognized him immediately, and the following, now immortal conversation took place. (I have given it in Japanese as well, so that you can best savour the moment in all its authenticity):

ME:

Hora! Chiyonofuji deshō?

Hey! Aren’t you Chiyonofuji?

CHIYONOFUJI

(as he sweeps past):

So da yo

.

Yup.

ME

(to the back of Chiyonofuji’s head as he continues down the street):

Komban-wa!

Good evening!

THE BACK OF CHIYONOFUJI’S HEAD:

No response.

There you have it, the Dumbest Conversation of the Decade. When I told my Japanese colleagues about my encounter with the Wolf, they cringed. For one thing, his name is no longer Chiyonofuji; he has been given a name of higher respect befitting his position. And for another, one does not just go up and talk to a man as great as Chiyonofuji. (I was lucky he even responded at all.)

Mere moments after humiliating myself with Chiyonofuji, I ran into several other rikishi. One stout fellow was getting into a cab and I hurried over on the assumption that he would probably be thrilled to shake my hand. It was Kotonishiki, always easy to recognize because he looks just like Essa Tikkanen, a hockey player whom you have never heard of either. I was a little more composed when I accosted Kotonishiki. I thrust my hand into his and said, “Do your best in tomorrow’s bout.” He nodded and said, “I will do my best.” And son-of-a-gun if he didn’t go out and win the very next day. I couldn’t help but feel partly responsible. And needless to say, I am now a

big

Kotonishiki fan.

Mr. Hiro Koba agreed that Kotonishiki had been very polite to have stopped to chat. (It helped that I had a hold of his hand and wasn’t prepared to let go until he acknowledged me.) Kotonishiki, meanwhile, went on to get caught in a twisted love-triangle sex-scandal, with a pregnant mistress and a wife betrayed, which the newspapers covered with an incredible eye for journalistic detail. The life of a rikishi, you just can’t beat it.

And so it was.

Instead of plumbing the depths of our souls, Hiro and I talked sports like a couple of regular guys. I think there is a fear, somewhere in the mind of the traveller, an unease with emotions laid raw and bare. I prefer width to depth, variety of experience to intensity of experience, quantity to quality. And there is something

about Japan—the surface reflections and refracted lights—that allows you to skim across without having to sink below. Japan does not swallow souls whole, as do some countries. Countries like India. China. America.

Japan is a nation perfect for hitchhikers, and one of the great appeals of hitchhiking is that it is a transitory experience. You cut through lives in progress, the rides flip by like snapshots, and the people become a procession of vignettes. I was not searching for catharsis or murky depths, I was searching instead—for what? I suppose I was hoping, somehow, to find in this pixilation of people and places something larger, an understanding, if not of Japan, then at least of my place in it. It was not a quest—that is too grand a word for it. It was more of a need, an itch, quixotic at best, presumptuous at worst.

So I left Hiro Koba to the privacy of his life, to his own singular joys and small defeats. He liked sumo, he missed Nagoya. That was enough.

17

T

HE CITY OF

S

AIKI

was built largely upon reclaimed land. This gives it a low, flat feel. The area around the port was arranged in a grid: square blocks, wide avenues, and box-like buildings. With several hours until the evening ferry, I wandered aimlessly through this forlorn town. It was the kind of place you expect tumbleweeds to roll through. Signs creaked on rusted hinges, and the stale smell of fish and diesel fumes had seeped into every house and plank. The paint was peeling, like eczema. Strangely enough, Saiki’s straight-square gridwork of streets actually made it harder to get around. It was a confusing place. Every corner looked vaguely the same. I passed a red-lantern eatery, walked for a few blocks, and then, seeing nothing better, I circled back only to get hopelessly lost. Block after block and still I could not find it. It was getting dark, and I made a list of places in which I would not want to live: Saiki, Saiki Port, near Saiki Port, and Saiki. Harbour towns either hustle with excitement or reek with lassitude, old urine, and turpentine. Saiki is of the old-urine-and-turpentine variety.

As I passed one doorway, I startled a little boy, maybe four years old. He was buttoned up from neck to ankle, the sure sign of an overprotective mother. She proved me right by coming out hurriedly and telling him in a hushed, frantic whisper,

“Kiwo tsukete! Gaijin wa abunai yo!”

a phrase which always stings me when I hear it: “Watch out! Foreigners are dangerous!” But the little boy was having none of it. He stood, mouth open, his eyes a cartoon of surprise.

“Good evening,” I said, first to him and then to his mother. She gave me a hypocritical little smile and a small bobbing bow. Her son, having regained the power of speech, burst out with “A-B-C-D! A-B-C-D! A-B-C-D-F-G-E!”

“Very good,” I said. “Did you learn that in kindergarten?”

To which he replied: “A-B-C-D! A-B-C-D!”

This was getting real annoying, real fast. “Can you say Hello in English?”

“A-B-C-D! A-B-C-D!”

I congratulated him on his prowess with language and said goodbye. His mother bowed again, more deeply this time, and said with grave sincerity, “Thank you very much,” though it wasn’t clear whether she was grateful to me for speaking with her son or for not robbing her and leaving her and her boy for dead. At moments like these I have to fight the overpowering urge to yell

“Boo”

and see how high they leap and how loud they shriek.

Then, at the next corner, I came upon the red-lantern café I had passed earlier, and I went inside.

There was a plump, aproned lady behind the counter, and when I came in she exchanged glances with the only other customer in the place, a thin man slouched over his noodles. He slurped them up noisily, keeping an eye on me the entire time.

Above the bar were glossy photographs of Japanese battleships—not vintage Second World War destroyers, but modern, state-of-the-art vessels of prey. In one photograph a phallic grey submarine was emerging from the sea, the decks awash with foam and the Japanese flag emblazoned cross the aft or forecastle, or whatever the hell the correct seaman’s term is. As the lady of the place hurried herself with my curried rice, I pondered the significance of these photographs. I was wondering how a nation that claims to be the “Switzerland of Asia,” a nation whose constitution outlaws war and forbids it from ever having an army, I was wondering how such a nation managed to produce these lethal, sleek war machines. Except, of course, they aren’t war machines. They are part of Japan’s Self-Defense Force. Call it what you like, it is still a military buildup. I, for one, do not have a problem with this. Put yourself in Japan’s position. You’ve got North Korea aiming its warheads at you with a certified nutball at the helm, and you’ve got your crazy cousin China babbling away beside you, armed to the ears with Communist-era nuclear bombs—which means that eighty percent of them won’t work properly when fired. Unfortunately, twenty percent of Apocalypse is still Apocalypse. When you have

neighbours like these, maintaining primed-and-ready armed forces would seem to make a lot of sense. But why can’t they just come out and admit it? Why the big charade?

“

Oi

! Gaijin!” It was the other customer. He had addressed me in the rudest possible way. “Gaijin!

Chotto!”

Shit. Just what I didn’t need, a dyed-in-the-wool, one-hundred-percent certified Grade-A Japanese asshole. I tried to ignore him, but he became belligerent, speaking in what I think was a slurred Osaka accent.

“Oi!

You like that ship? You a sailor?”

“Sorry, I don’t speak Japanese.”

“Ha ha!” He called out to the lady, who was now bringing me my curry.

“Henna gaijin!”

(“Weird foreigner!”) Then, his eyes narrowing, he said, “I am Japanese.”

“Good for you.”

“I am a Japanese sailor. That ship,” he gestured with his jaw to one of the photos and in English said,

“Japanese, number one.”

And he sneered, his lips like eels.

There ought to be an archaeology of facial gestures. I am sure we could trace this particular expression—this eel-like sneer—all the way back to northern China. It is a mix of arrogance, utter contempt, and adolescent pride. In Japan it is usually more subtle than this caricature I was now up against. Sometimes it was so slight, you almost missed it. I once had a Korean customs officer sneer at me continuously for three hours straight as I was uselessly interrogated about nothing. When you get to China you see it more often. In Shanghai it is common even among young women. And by the time you reach Beijing, it is almost a permanent feature, more of an attitude than a facial expression. I do not doubt that somewhere out there, beyond the Great Wall in the outer steppes of Mongolia, there exists an old withered tribe, the wellspring of this sneer, the Ur-Sneerers, living in their huts, chewing skins, and spitting venom at one another. I was weary. I was weary of this tired old tune, this tinhorn anthem.

“Oi!”

he said every time I tried to ignore him. He was drunk, or at least pretending to be. He switched back to English,

“Japan! Number One!”

and to emphasize his point he held up his index finger. I responded with my middle finger. “I agree,” I said. “Number One!” But he didn’t catch, or didn’t understand, my insult.

I was trying to make this lizard man disappear but he kept inching closer to me, talking about how great, omnipotent, excellent, fully erect, etc., etc., the Japanese navy is. So I decided to take him down.

“Are you Korean?” I asked.

“What?”

“Are you Korean?”

He sputtered in disbelief. “Of course not! I am Japanese.”

“Oh, that’s right. You mentioned that. It’s just that, well, you look kind of Korean. I think it’s your eyes. Or maybe your mouth. Very Korean.” And that was it. I had destroyed him.

It is one of the eternal mysteries of Japan: Are the Japanese arrogant or insecure? Deep down, deep inside: insecure or arrogant? Arrogant or insecure?

“Well, have a good night,” I said with a smile. And, having driven the poor man to the point of apoplexy, and hopefully given him a lifelong complex—

Do I look Korean? Really? Do I?

—I paid for my curry rice and got up to leave. Just as I was about to go, I did the cruelest thing you can possibly do if you are a foreigner in Japan. I laughed at him. Not loudly, you understand. More of a chuckle, really. His face was purple with bottled rage, but fortunately—this being rural Japan—he did not follow me out of the café and beat me senseless. Instead he sat, seething in his own bile, and I left.

It was a hollow victory, of course. No doubt he now hates all foreigners on sight, and I have probably added to the already strained relationship between Japan and the West and created bad karma and misused my role as international ambassador of goodwill and poisoned the well of human kindness and killed the bluebird of happiness, but what the fuck, it was worth it.

I walked toward the white-bright phosphorous lights of the harbour, down to where the ferry was tethered. A group of boys, killing time on a spring evening in Saiki, were on their bicycles by the dock waiting for the ferry to leave. When they saw me, a mini-pandemonium broke out. They yelled, “Hello!” “This is a pen!” and other such witticisms. (Or more accurately,

Harro! Zis is a ben!)

“Gaijin-san! Gaijin-san! Are you ging to Shikoku? You are? Did you hear that, he understands Japanese! Goodbye, Gaijin-san! Goodbye!”

The ferry bellowed once, twice, and the motor began rumbling. Cars were filing on, their headlights on low beam. “Say something in English! Gaijin-san, Gaijin-san, say something in English!”

“I have never eaten feces knowingly!”

And on that note, I said farewell to Kyushu.

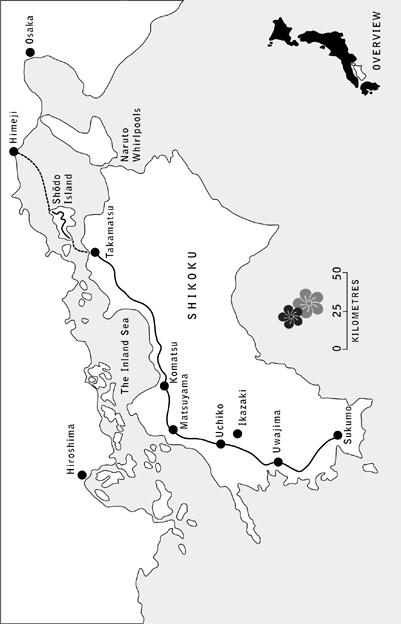

T

URNING

C

IRCLES

Shikoku and the Inland Sea