History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (53 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Retiring in 1837, Old Hickory tried to reeducate his son, but to no avail. Even in death, Jackson Sr. continued to pay dearly. Passing away in 1845, he left the thousand-acre Hermitage to Andrew. Within a year, the indebted heir began selling off small plots to pay creditors. Soon the entire property was mortgaged. By 1855, he was selling over half the property to the state of Tennessee. Mercifully, the state permitted Andrew and his family to remain on the property as caretakers.

In 1865, his ineptitude finally caught up with him. Careless with guns as well as with money, Andrew Jackson Jr. accidentally shot himself while hunting. He died soon after.

No other administration came closer to eliminating the national debt than Andrew Jackson’s. In early 1835, the debt was down to a few thousand dollars. At one point, the U.S. federal government owed creditors less than what Andrew Jackson Jr. did.

4

. JANE MEANS APPLETON PIERCE (1806–63)

FIRST LADY

She was emotional, selfish, and passive aggressive. If she could, she would have voted against her husband in the 1852 elections, for Mrs. Franklin Pierce never wanted to see him in public office, let alone the presidency.

Jane Means Appleton was born in 1806 to sternly religious parents, and early on she displayed a conspicuous lack of mental and physical toughness. In the parlance of the times, she also suffered from depressions of the mind. But when Jane was twenty, she fell in love with a handsome lawyer from New Hampshire, and they courted for eight years.

It was a hard road. Her family members were staunch Federalists; he was a Democrat. She was a teetotaler; he drank. She was shy; he was outgoing. She hated politics; he had ambitions. They loved each other, but soon after their wedding in 1834, their continuous fighting began to strain the relationship.

The marriage struggled further when two of their sons died in infancy. Jane thereafter became extremely possessive of her husband and their last surviving child, eldest son Bennie. Against her wishes, Franklin accepted the nomination of his party for the presidency in 1852. His surprise victory only filled her with misery, which deepened interminably when the Pierce family took a train ride to a friend’s funeral. Along the way, the cars derailed at high speed. The president-elect and his wife were slightly injured. Eleven-year-old Bennie was not as fortunate. His head was crushed in the wreckage, and he died instantly. Mentally, his mother never recovered. She later rationalized that God took her son away so that her husband could devote all of his time to being president.

38

Jane chose not to attend the inauguration or most of Franklin’s public events. She instead spent most of her time secluded in the second story of the White House, sporadically consulting spiritualists to contact her dead sons and writing long letters to Bennie. Most of the social duties of first lady were taken over by Varina Davis, wife of War Secretary Jefferson Davis.

A rare moment of joy came when the Democrats refused to re-nominate her husband in 1856, and the couple retired to their home in Concord, New Hampshire. Subsequent trips to the Bahamas and Europe failed to bring Jane out of her deep depression, and she died of pneumonia at the height of the Civil War.

To get away from the White House, Jane Pierce would occasionally take boats trips on the Potomac with family friend Nathaniel Hawthorne.

5

. MARY TODD LINCOLN (1818–82)

FIRST LADY

He was no treat to live with—slightly manic depressive, prone to brooding, excessively folksy and disheveled. In the words of his wife, “You can see he is not pretty.”

39

She was worse—materialistic, controlling, jumpy, a portly pixie with a belly full of issues. Perhaps her least pleasant trait, she was an incurably envious creature. Mary frequently accused her husband of being unfaithful, going so far as to throw him out of their Springfield home. On more than one occasion she physically attacked him.

More like counterweights than a couple, the Lincolns stumbled up the sociopolitical ranks, tempering each other’s worst elements along the way. He might have never reached the presidency had it not been for his wife’s unique ability to simultaneously love and prod him. But once in the White House, Mary was out of her element, and critics let her know it. From a slave-owning Kentucky family, she was too Dixie for Republicans and too Midwest for Washingtonians. Southerners damned her for the unforgivable sin of being Mrs. Abraham Lincoln.

Had there been no Civil War, she might have weathered such predictable barbs. But the conflict only intensified the pressure, and she stumbled often. She meddled in political appointments, publicly criticized cabinet members, and labeled U. S. Grant “a butcher” for his costly performance at Shiloh. Suspecting she was a Southern sympathizer and possibly a spy, a congressional committee secretly investigated her connections. One of the few character witnesses to speak on Mary’s behalf was her husband.

40

In her defense, she had lost several relatives in the war, plus her beloved eleven-year-old son Willie to typhoid in 1862. Constant media attacks against her husband only eroded her fragile state, and she lost most of her few friends.

But she utterly failed to connect with the suffering American public, embarrassing her husband time and again with expensive shopping sprees and public tantrums. Her worst move was to stage a major redecoration of the White House when others were struggling to get by without their husbands and sons. From the finest suppliers in Europe, she bought custom furnishings, brass fixtures, and ornate carpets. She also insisted on adorning herself in custom silk dresses for every occasion, when the nation was losing an average of two thousand soldiers a week. Unbeknownst to the struggling country, the president’s wife had also gone 30 percent overbudget on the federally funded redecoration project.

41

Little wonder why she had such a difficult time finding someone to accept her invitation to Ford’s Theatre less than a week after the triumph of Appomattox. Rejection followed rejection, until a senator’s daughter and her fiancé consented to go. As the couples enjoyed the play, Mary grew suspicious that Lincoln was trying to flirt with their young female guest. Moments before a bullet ripped through his brain, the president told his wife to not be so possessive.

Before she settled on Lincoln, the young Mary Todd was briefly courted by a shorter but more famous Illinois politician named Stephen Douglas.

6

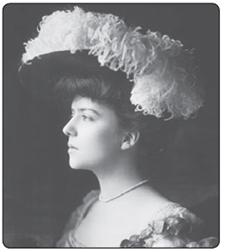

. ALICE ROOSEVELT (1884–1980)

DAUGHTER OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT

“I can either run the country or attend to Alice,” Theodore Roosevelt admitted. “I cannot possibly do both.” For a city that lived on intrigue, TR’s eldest daughter was an eternal feast. Rightly christened “Washington’s other monument,” she was an alluring and insatiable debutante who faithfully lived by her mantra: “If you haven’t anything good to say about someone, come and sit by me.”

42

Entering the White House at seventeen, Alice possessed the assured countenance of a monarch and the sinewy outline of a poet’s siren. Much to the dismay of her father, she was also extremely independent. She smoked in public, drove fast cars, flirted with older men, and kept the media guessing on her many romances. When speeding through the countryside, she adopted TR’s habit of shooting pistols at trees. Vocally irreverent to high society, yet perpetually in it, she would wake at the crack of noon to attend premier parties on a nightly basis, where she would adorn herself in long gowns of “Alice Blue” and mingle while her pet garter snake slithered along the embroideries of her bodice. An adoring press accurately named her escapades “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.”

43

She was undeniably Theodore’s daughter—but he could not bring himself to look at her. He never could, not since she was two days old.

On St. Valentine’s Day, 1884, New York Assemblyman Roosevelt had just returned to his home in Manhattan to see his beloved wife and their newborn daughter. They appeared to be doing well, when word came from downstairs that his mother was dying. She had been suffering from a severe cold—more than likely it was typhoid. Sometime around 3:00 a.m., Mittie Roosevelt passed away. Inconsolable, Teddy returned upstairs to discover that his wife was experiencing kidney failure. Hours later, she died in his arms.

44

From then on, TR repressed all traces of his bride, blotting her name from diaries, removing her photo from scrapbooks, refusing to mention her name in his autobiography. He would marry again, this time with guarded affection. His second wife, Edith, would give him five more children, all of whom he adored. But his relationship with Alice was forever strained.

She found it all confusing and painful. “Father doesn’t care for me,” she confided, often wondering what she or her mom had done to deserve such alienation. It may have never dawned on her that she and her mother shared the same name and that Alice represented the only thing Theodore Roosevelt ever feared—the memory of the worst day of his life.

45

To avoid speaking her name, Theodore Roosevelt called Alice by a myriad of nicknames, including “Sister,” “Baby Lee,” and “Mousie.”

7

. JOSEPH PATRICK KENNEDY SR. (1888–1969)

FATHER OF JOHN F. KENNEDY

A ruthless businessman, flagrant womanizer, and anti-Semite, he endorsed appeasement with Adolf Hitler and financially backed Senator Joe McCarthy. Yet his son became president largely because of Joseph Patrick Kennedy rather than in spite of him.

46

Early on, the patriarch taught his nine children the supremacy of image, especially winning. It mattered not what was involved—Wall Street, touch football, sexual conquest, or federal politics—so long as the family came out in front. As Joe once said to a young Jacqueline Bouvier, “All of us Kennedys don’t like second prize.”

47

The drive came at a price. When twenty-three-year-old daughter Rosemary showed signs of mental illness, which sometimes manifested in violent outbursts, Joe submitted her to a lobotomy on the assumption it would make her more manageable. The procedure instead reduced her to a permanent vegetative state. When second son Jack won the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for heroics in the Pacific theater, the father showered the young man with praise. The blatant and sudden favoritism motivated eldest son Joseph to volunteer for several dangerous missions over occupied France, one of which resulted in his death.