History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (45 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

The Quasi War, or the Half War against France, was never declared, and it was fought entirely on water, which was a bit of a problem for the Americans because they only had three modest warships. Long decommissioned were the Continental navy and their companion privateers. To rectify the problem, Adams signed into existence the Navy Department on April 30, 1798, and saw the construction of six frigates, the most celebrated being the USS

Constitution

with forty-four guns. They would be a small but formidable force.

There was no clear start to the fighting and no conclusive final battle. By diligent pressure on both the high seas and the diplomatic front, Adams was able to save his fragile state and its precious navy from a major engagement. Working with tacit cooperation from Britain, his handful of frigates and smaller warships began to capture smaller French ships-for-hire, avoiding the larger battle frigates of the French navy. In February 1799 came the first true victory, as the thirty-six-gun

Constellation

defeated the equally outfitted

l’Insurgente

in the eastern Caribbean. By the end of the year, American crews caught twenty-six privateers hired by the French. In 1800, the haul more than doubled. In total, the U.S. Navy brought in nearly one hundred vessels, mostly raiders, losing only one frigate to enemy engagement in more than two years of fighting.

85

The conflict came to an end with a regime change in France. Unwilling to tangle with the pesky Americans any further, Napoleon Bonaparte negotiated a settlement to a war that never was. The United States regained its neutrality on the high seas, and the U.S. Navy was born—as were the marines. Armed with an experienced, confident, and expanded naval force, the country was prepared to fight its next foe: the Muslim city-states along the Barbary Coast of North Africa. For the president, all his achievements went for naught. A month before the Senate ratified the treaty to bring the Quasi War to an end, Adams lost the E

LECTION OF

1800 to his vice president, Thomas Jefferson.

86

Suspecting France would invade, Congress authorized Adams to form an army of eighty thousand (four times larger than the Continental army ever was). Adams in turn named George Washington as commanding officer. The invasion never came, the army was never formed, and Washington died a year after the nomination.

9

. THEODORE ROOSEVELT

THE GREAT WHITE FLEET (1907–9)

Upon leaving office in 1910, the antagonistic Theodore Roosevelt was nonplussed that he had not presided over some great conflict. Looking back at other legacies, he contended, “If Lincoln had lived in times of peace, no one would know his name now.”

87

Contrary to Roosevelt’s opinion, trial by fire does not guarantee presidential immortality. Among the most famous chief executives, Teddy stands well above James Polk and William McKinley, victors in major wars that greatly expanded the boundaries of American dominion. Wartime president James Madison was known more for his work in creating the Constitution, and the immortal George Washington avoided international tangles like the plague during his presidency.

While TR may have romanticized combat as the ultimate test of personal and national manhood, as president he was militarily active but not particularly belligerent. His R

OOSEVELT

C

OROLLARY

justified limited engagements in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Panama. In 1903, U.S. troops landed in Syria to protect the American consulate from a suspected attack by radical Muslims. On the other side of the globe, marines performed a similar duty in Korea as Japan fought (and defeated) Russia over control of the Korean Peninsula. In 1906, Roosevelt tried to stabilize Cuba by partial occupation. But his greatest success came from a peaceful use of power, one that would embody his worldview and earn the respect of continents.

The idea emerged as a reaction to racial tension on the California coast. A large influx of immigrants posed a threat to the white population. Willing to work longer hours for less pay, the outsiders were also placing their children into the school system. In October 1906, the board of education in San Francisco began to segregate these “outsiders,” sparking riots in their native land. Gravely upset at the ethnic hatred within his own borders, the president called the whole affair “a wicked absurdity” and feared it would lead to greater violence. Relations between the United States and Japan had never been worse.

88

Advisers suggested he transfer the bulk of the Atlantic fleet around the Horn of South America to San Francisco Bay. It would take perhaps three months, but it would work to calm both the local population and be seen as a show of force against any possible actions from Tokyo. Roosevelt had a better idea. Rather than make a slow, small, pugnacious demonstration for minimal gain, he envisioned a voyage for the history books.

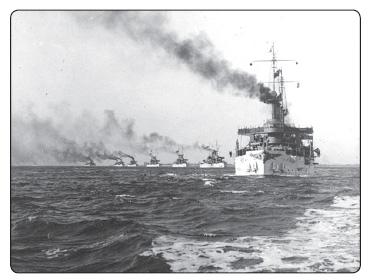

It would be called the “Great White Fleet.” With hulls painted in ivory and bows trimmed in gold, the mighty American warships would circumnavigate the globe. The world would see the iron might of the United States through a peaceful, headline-grabbing tour rather than from the barrel of a gun. When rival nations declared it could not be done, not on such a grand scale, TR became all the more committed. Navy officials asked how many of its sixteen battleships should be sent. Roosevelt responded with a simple order—all of them.

89

The idea was not popular. Cities on the coast protested that they were being stripped of their defense. Congressmen believed TR was secretly hoping to provoke a war with Japan and end his presidential career with a glorious victory. Teddy ignored them and ordered the fleet away.

Roosevelt’s intuition proved correct. The armada was welcomed all along the shores of South America. By the time it reached California, the Tokyo government had warmly invited the vessels over. Eagerly accepting, U.S. sailors and marines reached Yokohama several weeks later and were serenaded by excited Japanese schoolchildren singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Port after port, curious and admiring populations gawked at the spectacle of mighty craft drifting in.

By 1909, the ships were safely back at Hampton Roads. Without firing a shot in anger, and traversing more than forty-five thousand miles, they had achieved the seemingly impossible and earned the United States more goodwill and respect than it had since its inception. Welcoming them back in person was the same man who had seen them off, only he was fourteen months older and had but two weeks left in his final term as president. Beaming with immeasurable pride, Roosevelt assessed the trip and his legacy. “In my own judgment,” he concluded, “the most important service that I rendered to peace was the voyage of the battle fleet round the world.”

90

The Great White Fleet’s itinerary included visits to Trinidad, Brazil, Chile, Peru, Mexico, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Japan, China, Ceylon, Egypt, and Gibraltar before returning to port in Hampton Roads. Total distance—forty-five thousand miles.

U.S. Naval Historical Center

In 1908, the lengthy voyage of the Great White Fleet convinced Theodore Roosevelt that the Philippines were too far away to be practicably defended. Seeking a more defensible position, he officially transferred the U.S. Pacific Naval Base from Manila Bay to the Hawaiian port of Pearl Harbor.

10

. RONALD REAGAN

THE BOMBING OF LIBYA (1986)

Born at a time when thousands of Civil War veterans were still alive, Ronald Reagan possibly heard a few of them mention the golden rule of shooting—aim low. The Gipper was a nationalist, a militarist, un-worldly, and blindly patriotic, but he was not a warmonger. Though he took many opportunities to flex American muscle across the first, second, and third worlds, he never overcommitted nor overstayed an engagement, preferring instead to speak loudly and carry a small stick. In his first term alone, he deployed advisers, troops, and/or aircraft to Chad, Egypt, El Salvador, Granada, Lebanon, Libya, and the Persian Gulf. None of the engagements escalated beyond a few sorties, skirmishes, or short occupations. Even his I

RAN

-C

ONTRA

operation, though immensely illegal, was minuscule compared to the arms and money that LBJ and Nixon poured into Saigon. Reagan meant it when he said “no more Vietnams.” The consummate actor, Reagan knew when it was time to exit a scene.

91

On October 23, 1983, a suicide bomber plowed through the gates of U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut, killing 241 of the peacekeeping forces and injuring more than 100. Within two days, Reagan ordered a military offensive, not in Lebanon, but against the tiny Caribbean island of Granada, fearing that 800 American medical students there were in danger of a violent Cuban Marxist takeover. It took forty hours for a carrier task force and army rangers totaling 5,000 officers and men to conquer the island and its 800 Cuban defenders. The short, successful invasion was widely popular among the U.S. population, and it masked the pain of Beirut. Three months later, in a move favored by his cabinet and his country, Reagan pulled all remaining U.S. Marines out of Lebanon.

92

His most successful and least costly operations involved Libya and its verbose Islamic president, Muammar Qaddafi. Head of a country of fewer than three million, Qaddafi had enough oil in his country and anti-Americanism in his nationalistic veins to merit numerous public rants against Reagan. Intended more to impress everyone in Tripoli rather than anyone in Washington, the dictator’s rhetoric still offended the sensitive Gipper. Claiming “freedom of navigation,” Reagan sent a modest armada to the Gulf of Sidra in the spring of 1986, within miles of Libyan territorial waters. Qaddafi proclaimed a “line of death” across the gulf, and he all but dared the cowboy president to a shootout on Main Street. An exchange of rockets in late March upped the ante.

93

When an American serviceman was killed by a bomb in a Berlin nightclub, Reagan had his cue to enter into a larger operation, from arm’s length. Launching air strikes from bases in Britain on April 14, 1986, the U.S. Air Force and Navy dropped ninety tons of high explosives on Tripoli and Benghazi, killing more than one hundred people, including Qadaffi’s adopted two-year-old daughter, but missing their main target. The strike nonetheless had the desired effect. With no losses on his own side, and no long-term occupation on the ground, Reagan effectively neutered the Libyan leader’s war of words. Though the international community condemned the bombings, a majority of Americans viewed the strikes as a show of legitimate strength. From a line straight out of a dusty Western, Sheriff Reagan proudly announced to the townsfolk: “Every nickel-and-dime dictator the world over knows that if he tangles with the United States of America, he will pay a price.”

94

Under the War Powers Act of 1973, a president must first inform Congress if he plans to send U.S. forces into hostile areas. In his 1986 air strike against Libya, hours before U.S. bombers reached enemy airspace, Reagan told a few key legislators about the operation, thus obeying the letter of the law.

When the drafted Constitution emerged in September 1787, not a few civilians were shocked to read of its ample provisions for making war. To the wary, the idea of having a standing army in peacetime ran counter to the revolutionary ideal, itself begun as a protest against quartered troops, military governorships, and imposed taxes to pay for them. In addition, to have a president serve as commander in chief seemed like an open invitation for another Julius Caesar or Oliver Cromwell or George III.