Authors: Carl Hart

High Price (19 page)

“You want to do something?” one of the instructors said.

“No, sir,” he responded.

“Why the fuck you looking at me? You calling me a liar?” And on it went.

I knew right then that I’d never be the same. There were three instructors, all at least as powerfully muscled as the most fit recruits and full of pride. They came at him like they were going to kick his ass, getting in his face as he stood there sweating. The guy knew he couldn’t fight back, so he tried to respond as submissively as possible. Then one of the trainers said to one of the others, “Sergeant Castillo, hold my shit. I’m gonna fuck this motherfucker up!” The man stiffened, unsure what to do. By the end, he looked like he was close to tears.

Watching them push him to see if he would snap, I knew that I had a choice of my own to make about how I would behave. I could buckle down and do what I had to do and maybe get something out of this, or I could be a clown and continue aimlessly, taking nothing but sports and street status seriously. I could let these authorities defeat me by dropping out or I could be serious and stay. I thought about my sisters back home and I didn’t want to let them down. They had seen the military as a new start for me and as a way out of the dead-end jobs that seemed destined to be my future otherwise. Along with Big Mama, they had encouraged me and mothered me, placing so much of their hope for the future in me. I couldn’t stand the idea of disappointing them.

Although I still had big dreams about basketball, somewhere inside, I knew that fully grown at five foot nine, despite my talent, the odds were against me having any kind of professional career. If I was going to make something of my life, it had to start here and now and I had to have a different attitude. I wasn’t going to let any of those sorry, out-of-shape recruits I saw in my squadron do better than me. Luck may have helped me get there, but that epiphany and my own hard work that followed were what allowed me to take advantage of the opportunity. There would be many chances for me to fall down and be pulled back—but the first day of what we were told to call “basics” turned my head. We were all relieved when the instructors dismissed us and we finally were allowed to get a couple of hours of sleep.

And once I resolved to put in the effort, there was not much else to do other than submit to the experience and do the work. Although most people find the constant exercise in boot camp to be physically grueling, I found that I faced a different challenge. At home, I’d played a minimum of several hours a day of basketball in games and practice, constantly running and doing specific drills to keep my edge. That didn’t include pickup games and other athletic activities I did just for fun. In basics, we were being trained so that after six weeks, we’d be able to run a mile and a half as a squadron. And we had to go at the pace of the slowest man, who was seriously slow.

To be fair, it was San Antonio, Texas, at peak summer heat and not everyone had grown up in Miami and become acclimatized to intense exercise in high temperatures. But I felt like I was teasing my body. When we were done working out, I’d barely even be warmed up. As a result, I wound up running push-up and sit-up contests with my bunk mates at night: I told the guys that we could all get out of here looking good if we made some additions to the routine.

Back home, brothers who had spent time in prison would typically return looking amazingly buff. They said that in the joint, they’d done those exercises constantly—so I reasoned that we should do the same in the air force. Pretty soon almost everyone in my squadron was doing it. We’d take bets on who would win with the highest numbers.

The only other thing to do at night was write letters home, which became another way to compete. The more letters you wrote, the more you would get back when the training instructor handed them out at mail call. Receiving lots of mail was a sign of high status. I wrote to all my girlfriends, as well as my sisters and brothers.

And as with its use of psychology to break us in with exhaustion and boredom, I found that the air force was far more adept than I expected it to be at dealing with racial issues. In their history of how the army (and by extension, the rest of the military) became the most integrated institution in America,

All That We Can Be

, sociologists Charles Moskos and John Sibley Butler wrote that the service is “not race-blind, it is race-savvy.” That’s how I felt about it. The air force had been the second of the services to desegregate and was the first to become fully integrated.

I was amazed by how quickly the military got everyone—black, white, yellow, brown—to work as a coordinated unit. They imposed rules to ensure we would get along and by giving us the common enemy of the training instructors and their strict command, united us in a shared experience. That created a bond. I first got a real sense that things worked at least somewhat differently in the military when I saw our dorm chief, a black guy, get demoted for giving favors to some of the guys in our squadron. Someone had dropped a dime on him (snitched)—a black guy. It simply blew my mind that a brother would give up another brother: when you grew up where I did, that just was not done in any setting that had real-world consequences.

Of course, the idea of being loyal to a mixed-race team wasn’t new to me—that had been part of athletics for virtually my whole life. Off the field, however, I’d always found that those allegiances were not as strong. Race was still foremost in people’s minds when it really came down to it. No one I knew believed that American institutions could really be fair to us. We’d all seen people who had faith in that get violently upended, whether through experience of police brutality or employment discrimination or just daily experiences of lack of respect.

There were peculiarities and misunderstandings, too: for example, the term

homeboy

was banned after white guys mistook it for an insult. They thought we were using it to demean people, to say they were homebodies who never went out and were antisocial. Of course, we were actually referring to friends, particularly people from our neighborhood that we liked. But it made whites uncomfortable, so it had to go.

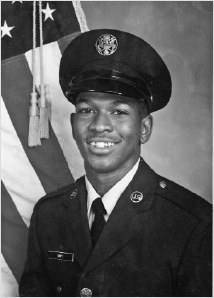

Basic training photo.

Still, such incidents were not as common as they were in the civilian world and overall, I felt like we were treated with respect based on how we behaved, rather than on race. The military rules were clear and felt less capricious. I began to change my attitude and become more open and hopeful about the future.

I have to emphasize here, however, that I did not change overnight.

There was nothing sudden at all about my transformation from a kid with a poor education who knew little about the history of my people and the ways of mainstream America into someone capable of becoming a tenured professor at an elite university. I only gradually became aware of the gaps in my knowledge, and the analysis that I undertook would allow me to transcend them by understanding their roots and the forces that shaped my family and neighborhood. I didn’t go instantly from being an indifferent student to one who spent hours in the lab. And I certainly didn’t change from someone whose focus was primarily on my social life into a serious academic simply by joining the air force.

But the air force was the environment that allowed me to start to make these changes, to start to understand what I’d missed in my earlier education and my own capacity for change. My commitment to the service made in boot camp was only the beginning. There would be many more times when I failed to make the best choices, when my lifestyle threatened to swamp my desire for a different life and when the pull of the reinforcers I knew was stronger than my commitment to my future. In fact, my college education itself started in part because of a choice I made to take drugs to be cool with my friends.

A

n imposing Bob Marley poster hung on Mark Mosely’s door, larger than life, showing the reggae star onstage at the height of his power. Bob’s dreads were arrayed around him as he sang into the mic. The scent of incense—typically sweet jasmine—wafted into the hall from Mark’s dorm, but the poster was hung on the back of the door, visible only from inside. His window shades were usually pulled down and the lighting was dim.

When Bob’s music was not emanating from a record on the Denon turntable or reel on the Akai 747, Mark played other reggae and jazz. His place looked like a revolutionary Afro-centric pad from the 1970s, but it was actually located in a recently built residence hall in Okinawa, Japan, on Kadena Air Base in 1985.

Several years older than me, Mark was a jet mechanic; I met him because we lived in the same building on the base in Japan to which I’d been assigned after I’d completed my initial training. His goal was ultimately to study sociology back home at the University of California. In the meanwhile, he would school other black airmen to raise our consciousness during our military service.

But—although some associate Marley and his music primarily with the marijuana that is a sacrament for his Rastafarian religion—Mark did not take illegal drugs. He didn’t burn incense to hide the odor of cannabis and he didn’t lower the lights to shelter eyes reddened by marijuana. The higher consciousness he sought involved intellectual and revolutionary enlightenment.

In fact, the marijuana smoking that led indirectly to my college career occurred in a different social setting. I got high with another group of friends in Japan. It was during this time in Okinawa that I began to realize that I would have to make some real decisions about the peers with whom I surrounded myself because the ideas and habits that I shared with them would be an important influence on my future. Like I’ve said, I didn’t become studious and intellectually driven overnight. Mark was a powerful force in my education, but there were competing elements. At first, it wasn’t at all clear that I’d manage to keep my commitment to myself, my sisters, and the service.

I

’d originally been slated to go to Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas, rather than overseas. But my cousin Cynthia, whose husband was in the air force and stationed at Kadena, convinced me to swap with another new recruit and join her and her family in Japan. I knew nothing at all about Japan or its culture. I did know that a girl I was seeing was going to be sent there. I thought it would be interesting to see another country, and having a friend-girl and at least some family there would make the transition easier. It seemed as good a place to start as any. As far as I was concerned Okinawa was the same as Tokyo, and Tokyo was like any big city in the United States. Boy, was I wrong.

I didn’t realize that my cousin had told me only the good things, hoping she’d be able to get me to join her church there so she could save my soul. I quickly made it clear that that was not on my agenda. And I rapidly learned as well that Okinawa had a reputation as being a hardship post for single men, known disparagingly as a prison island and dubbed “the Rock.”

It was especially difficult for black folks. Racism in Japan felt more conspicuous than it had growing up in the American South, perhaps in part because I wasn’t expecting it. But the Japanese had seen all the American movies and they knew who the niggers were. On more than one occasion, shopkeepers off base actually used that word to refer to me to my face. Even when it wasn’t that overt, it was clear that I was being treated like a second-class person in many of my interactions with the locals.

Still, the most disturbing thing to me about Japan was the lack of American servicewomen. So few American women were stationed there that I regretted my choice almost immediately. It was almost as bad as in boot camp, where the men and women were completely separated. Of course, outside the base on Gate 2 Street, everything from tennis shoes to sex was being sold, a plethora of cheap, ephemeral products and pleasures. I had too much pride for that. I wasn’t the kind of brother who had to pay for sex.

Even stranger was living away from my family, and all its noise and bustle, for the first extended period in my life. Until we’d moved to the projects when I was in high school, my mother had never had more than a two-bedroom home, which meant that up to six of us siblings—girls and boys—shared one bedroom. My grandmothers’ and aunts’ homes hadn’t been any less crowded and the barracks during basics weren’t much different.

Now, though, sharing a room with just one guy was eerily calm to me, especially since the roommate in question probably had what we’d now call Asperger’s syndrome. A white guy, he specialized in languages and knew five of them. But although he drank heavily like many airmen, he never wanted to go out. He didn’t want to hang out with anyone; he just drank in our room alone. For some reason known only to him, he’d sit there and watch the movie

Trading Places

over and over and over again.

I thought my unease and difficulty sleeping was related to his peculiar behavior, so I got another roommate, a brother I dug a lot. But no, the deep silence of living in a place that wasn’t inhabited by a large family, that didn’t involve frequent social interruptions, remained mind-numbing to me. It drove me crazy.