High Heat (30 page)

Authors: Tim Wendel

What exactly did Rogan's no-windup delivery look like? Allow historian Paul W. Fisher to describe the scene:

Every eye is trained on the mighty Rogan. He is a trim, square-shouldered, deep-chested man, with slim legs and hips. He brings his hands softly to his belt buckle, his hips begin to pivot slowly right, the hands come slowly and softly toward his face and thenâ

His right arm has swept back quicker than the eye, whipped around and over and at slightly less than three-quarters motion. In the yellow afternoon, a mote of white light flies from his black hand. The fortunate among the thousands caught its split-second speed; even at the far reaches of the roped outfield, they heard its crash into [Frank] Duncan's big glove. WHAP!

What we have here is a pitcher intent on getting batters out in a hurry.

“Live high fastball and hard sharp breaking curveball that we called a drop ball,” O'Neil says of Rogan. “Strikeout pitcher. Excellent athlete. Hit fourth in the lineup when he played the outfield. Very desirable. Bob Feller type.”

Was he better than Paige?

“I don't know,” Bobby Williams, a veteran shortstop in the Negro Leagues told John Holway. “He was good, but I wouldn't say he was greater than Paige. But Rogan was another infielder when he was pitching, he could play outfield, he could hit. Paige couldn't do anything but pitch.”

For much of his career, even though it rarely showed on the field, Paige was bothered by an upset stomach, especially in high-pressured games. He nicknamed his stomach troubles “the miseries,” and initially the condition was blamed on big-game stress and fast living. Several doctors wondered if he had ulcers. It wasn't until

late in his career, between the 1948 and 1949 seasons, that the real culprit was discoveredâlousy teeth. Paige's choppers were literally rotting away, so he had all of them pulled and went the rest of his days with ill-fitting dentures.

late in his career, between the 1948 and 1949 seasons, that the real culprit was discoveredâlousy teeth. Paige's choppers were literally rotting away, so he had all of them pulled and went the rest of his days with ill-fitting dentures.

“When your whole life may be depending on your stomach, you don't worry about having no teeth,” he later wrote. “You'll do about anything, even if you got to put a bunch of sticks in your mouth.”

After Paige got used to his “store teeth,” he prayed and waited to see if the old stomach ailments would return with the same vengeance. “But those pains weren't coming back like they used to,” he said. “They were there, but not like they'd been all through the last season.”

Teeth problem aside, what made Paige unusual among legendary pitchers was his miraculous comeback from a bout of arm trouble that would have ended most careers and perhaps reduced him to a footnote in the search for the top fireballer of all time.

In 1938, Paige was arguably at his peak. He had just returned from the Dominican Republic, where he and other Negro League starsâJosh Gibson, Schoolboy Griffin, and Cool Papa Bellâhad led Cuidad Trujillo to the championship. That team had been bankrolled by the country's dictator, Rafael Trujillo. Before the championship game, against Estrellas de Oriente, Paige's ballclub was sequestered in a guarded hotel. After they fell behind in the early innings, Trujillo's troops began to surround the diamond.

“You better win,” the Trujillo City manager told his all-stars.

They rallied for a 6â5 victory. Paige was on the mound, where he took a look around at all the weaponry and figured he was pitching for his life.

After that near-death experience, Paige and the others hurried back to the United States. While the other Negro League all-stars stayed close to home, Paige was looking for another big payday, so he ducked out of his agreement with the Pittsburgh Crawfords and headed to Mexico.

“Being greedy like that just about ended my career,” he wrote,

“and just about cost me a couple or three times the money I was making for those few games in Mexico.”

Three games into the season, Paige felt what was at first a burning sensation in his arm. A few days' rest didn't help. In fact, the burning gave way to numbness. Paige began to run a fever, and soon after he couldn't even lift his arm above his head.

In desperation, he went down to the stadium and, without bothering to change into his uniform, tried to throw. The ball only traveled a few feet and Paige headed home the next day. He was examined by several specialists. One told him he would never pitch again.

Paige was only 32 years old. A typical ballplayer would usually have several more years in him. But in the world of high heat, the fall from star to mere mortal can be sudden and unexpected.

“I didn't want to see nobody,” Paige later said in his autobiography. “I could see the end. Ten years of gravy and then nothing but an aching arm and aching stomach. Oh, I had my car and shotguns and fishing gear and clothes.

“I had those, all right, and they were all mighty fine. But you got to make money to keep them and when you ain't making money and when you ain't saved money, they go fast.

“Mr. Pawnshop must have thought I was a burglar the way I kept coming back to see him with another shotgun or another suit.”

Sucking up his pride, Paige got a job as a pitcher/first baseman on the Kansas City Monarchs' barnstorming squad. With another Negro League season under way, the team was essentially a backup squad. They toured the Northwest and Canada, playing whenever they could. Paige often heard it from the crowd when he took the mound. They came to see the fabled fireballer and instead all he would deliver was soft stuff, sidearm and even underhanded. When Paige's arm showed no sign of coming around, he was moved to first base. His goal was to save up some money before returning home to Mobile, Alabama.

But one day, before the next game, Paige began to warm up on the sidelines. Even though he was playing first base, a position that didn't require much throwing, Paige threw repeatedly in warm-ups. It was the only way to push the pain in his arm toward numbness.

But on this day, there was no pain when he threw. He called the catcher over and began to throw harder to him. Knut Joseph, the manager, was summoned and proceedings shifted to the pitching mound. There, Paige threw pitch after pitch, putting more and more effort into each one, beginning to kick his leg toward the heavens in that classic pitching motion of his. With each delivery, the velocity increased and, more importantly, the pain didn't return.

But on this day, there was no pain when he threw. He called the catcher over and began to throw harder to him. Knut Joseph, the manager, was summoned and proceedings shifted to the pitching mound. There, Paige threw pitch after pitch, putting more and more effort into each one, beginning to kick his leg toward the heavens in that classic pitching motion of his. With each delivery, the velocity increased and, more importantly, the pain didn't return.

The catcher and manager were both grinning by now. That evening Joseph called J. L. Wilkinson, the Monarchs' owner back in Kansas City. Even though Paige was eager to rejoin the parent club, Wilkinson, to his credit, refused to rush things. He told Paige to stay with the backup club for the rest of the season, to get back in shape. It wasn't until the spring of 1939âat the age of 33âthat Paige's comeback began.

“After my arm first came back, I didn't know for sure I could blaze away until I got back into some games and really had to,” Paige said in his autobiography. “I could. That hummer of mine sang a sweet song going across the plate. It was the finest music I'd ever heard.”

Paige would later call his recovery “a miracle.” With his arm better than ever, he rejoined the Kansas City Monarchs for the 1939 season and finally got his chance to play in the major leagues nine years later.

Â

Â

T

he scar has long ago faded to just a thin white line, riding the inside of the elbow joint on Tommy John's famous left arm. After retiring as a player in 1989, with a 288â231 record and 3.34 ERA, John still found ways to stay in the game. He was a coach, a broadcaster, and, as the 2009 season began, in his third season as the manager of the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Bluefish in the Atlantic League. Over the years, he's had several players on his teams who've had the operation he made famous. In fact, one guy even had Tommy John surgery twice.

he scar has long ago faded to just a thin white line, riding the inside of the elbow joint on Tommy John's famous left arm. After retiring as a player in 1989, with a 288â231 record and 3.34 ERA, John still found ways to stay in the game. He was a coach, a broadcaster, and, as the 2009 season began, in his third season as the manager of the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Bluefish in the Atlantic League. Over the years, he's had several players on his teams who've had the operation he made famous. In fact, one guy even had Tommy John surgery twice.

Such notoriety hasn't brought him any closer to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, however. Before the 2009

season began, it was announced that John received only 31.7 percent of the votes from the baseball writers, well below the 75 percent required for induction. The bid was his last attempt. While John could someday gain entry through the Hall of Fame's Veterans Committee, he isn't counting on it.

season began, it was announced that John received only 31.7 percent of the votes from the baseball writers, well below the 75 percent required for induction. The bid was his last attempt. While John could someday gain entry through the Hall of Fame's Veterans Committee, he isn't counting on it.

“It is what it is,” he says as his Bluefish take batting practice. “It's not something I have any control over, so why worry about it? The guy who I'd really like to see make it to Cooperstown is Dr. Jobe.”

John tells how it was Dr. Jobe's idea to cut along the original incision made to remove the elbow chips in 1972. How it made sense to follow that “road map,” as the doctor told him, and leave the surrounding muscle areas undisturbed. Over the years, John has come to believe that it was such subtleties and attention to detail that made all the difference.

“I was lucky,” he says. “I happened to be on a team with the best doctor in the world to do such a thing. He rolled it all out for me, never kept me in the dark about what was going to happen. Now the surgery has become almost run of the millâyoung kids are even getting it. But it sure wasn't run of the mill back then. All of us were taking a huge chance.”

Someday John would love to coach at the big-league level. Yet he wonders at age 66 if he's perceived by baseball's powerbrokers as being too old, just another baseball lifer past his prime. The surgery, that stroke of genius when an unnecessary tendon from John's right wrist was used to reconstruct his left elbow, will be the headline on his obituary, and he knows it.

“And that's fine,” John says. “Maybe that's how it should be. In an ideal world, the procedure should really be named after Frank Jobe. He's the one who drew it up. I was just the guy who needed it.”

But then he smiles, adding, “That said, I wouldn't mind a hundred bucks for every one that's been done since I went under the knife. That would be OK with me.”

The Follow-Through

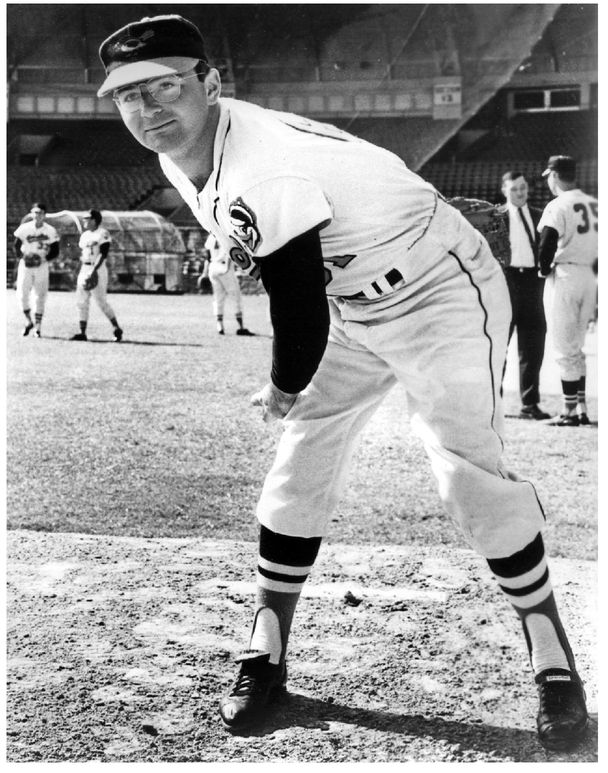

Steve Dalkowski

Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY

I am convinced that life is 10 percent what happens to me and 90 percent how I react to it.

âCHARLES SWINDOLL

Â

Â

Show a little faith, there's magic in the night.âBRUCE SPRINGSTEEN

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

T

ornadoes were sighted in the Dallas suburbs last night, and now in the morning dark clouds ride the western horizon. The gusting winds cause the lights to flicker inside Nolan Ryan's executive office. The man they call “Big Tex” in these parts barely acknowledges the ongoing cracks of thunder and flashes of lightning. From his perch high above the playing field at Rangers Ballpark in Arlington, Texas, he wants nothing more than to get in tonight's game against the visiting Toronto Blue Jays. The previous night's contest was canceled. So much rain fell that not even the Rangers' high-tech field, capable of siphoning off up to 10 inches per hour, could keep up with the onslaught from Mother Nature.

ornadoes were sighted in the Dallas suburbs last night, and now in the morning dark clouds ride the western horizon. The gusting winds cause the lights to flicker inside Nolan Ryan's executive office. The man they call “Big Tex” in these parts barely acknowledges the ongoing cracks of thunder and flashes of lightning. From his perch high above the playing field at Rangers Ballpark in Arlington, Texas, he wants nothing more than to get in tonight's game against the visiting Toronto Blue Jays. The previous night's contest was canceled. So much rain fell that not even the Rangers' high-tech field, capable of siphoning off up to 10 inches per hour, could keep up with the onslaught from Mother Nature.

As the tempest rages outside, Ryan glances at the scouting reports for his ballclub's 2009 top picks. A few days ago, baseball's annual draft was held, with fireballer Stephen Strasburg going to the Washington Nationals as the first selection overall. As president of the Texas Rangers, Ryan has a major hand in his team's draft strategy. The old baseball assertion that you can never have enough pitching rings

as true today as it did a century ago. With that in mind, Texas selected a pair of pitchersâMatthew Purke and Tanner Scheppersâas its first two picks. Purke fits the desired profile (left-handed, fresh out of high school). In comparison, Scheppers was a roll of the dice. After starring at Fresno State, he suffered a shoulder injury prior to last year's draft. As a result, he fell to 48th overall. Instead of signing, Scheppers pitched for the St. Paul Saints in the independent American Association. That's where Don Welke, the scout who championed Jim Abbott, and who now works for the Rangers, became convinced Scheppers could play at the big-league level.

as true today as it did a century ago. With that in mind, Texas selected a pair of pitchersâMatthew Purke and Tanner Scheppersâas its first two picks. Purke fits the desired profile (left-handed, fresh out of high school). In comparison, Scheppers was a roll of the dice. After starring at Fresno State, he suffered a shoulder injury prior to last year's draft. As a result, he fell to 48th overall. Instead of signing, Scheppers pitched for the St. Paul Saints in the independent American Association. That's where Don Welke, the scout who championed Jim Abbott, and who now works for the Rangers, became convinced Scheppers could play at the big-league level.

“Don's definitely in his corner,” says Ryan, who is just the third Hall of Fame player to serve as president of a major-league team. John Montgomery Ward (1912) and Christy Mathewson (1923 and 1925) are the others. “If it wasn't for Don Welke, we probably wouldn't have taken Scheppers, at least not that high. But when a scout with a track record like Welke's makes the case for somebody, you have to listen.”

But even if the science and the majority of scouting reports stack the deck against such a move? Unlike other team presidents, Ryan admittedly has a soft spot for scouts who wear their hearts on their sleeves. They remind him of Red Murff, the scout who years ago believed in him when the rest of the Mets' scouting staff had wanted to draft just about anybody else.

Here, in the days following the annual amateur draft, Ryan knows as well as anybody that the real challenge for any organization has only just begun. “The biggest thing young pitchers have to learn is to believe in themselves,” he says. “They don't have to possess the most remarkable arm to succeed. But they need to realize, very quickly, how important it is to throw strikes, to trust their stuff.”

Other books

The Boy in the Suitcase by Lene Kaaberbol

Parthian Vengeance by Peter Darman

Dream Horse by Bonnie Bryant

My Animal Life by Maggie Gee

The Lady's Protector (Highland Bodyguards #1) by Emma Prince

Empire of Storms (Throne of Glass) by Sarah J. Maas

After the Event by T.A. Williams

Falling Behind (Falling Series) by Dee Avila

A Winter's Promise by Jeanette Gilge