Hieroglyphs (16 page)

Authors: Penelope Wilson

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #Ancient, #Social Science, #Archaeology, #Art, #Ancient & Classical

Looking at a hieratic text, it is sometimes easy to see the pictorial hieroglyphs from which the signs derive. Whereas the sign for the seated man would involve carving the hieroglyphs in several stages, the hieratic reduces the number of times the reed brush needs to come to the surface of the papyrus or writing board or ostrakon.

A seated-man hieroglyph requires his head, body, arms, and legs to be drawn out carefully, while the hieratic version is a backwards S-shape with a vertical line drawn through it, completed in 72

Sign 1

: From a Dynasty 6 letter. The owl retains its ears and is still more a linear sign.

Sign 2

: From the Dynasty 18 Book of the Dead of Nakht.

This is a true linear hieroglyph.

Sign 3

: From the Dynasty 19 Papyrus Chester Beatty I,

‘Struggle Between Horus and Seth’. The sign is

now made in one movement and retains the

sense of the head and body, but the distinctive

ears and talons have gone.

Scribes an

d e

veryda

Sign 4

: From the beginning of the New Kingdom,

y writin

Papyrus Edwin Smith. A smoother, more

elegant version of the hieratic

m

.

g

14. Examples of the owl sign in various types or dates of hieratic

writing, all reading from right to left.

two or three quick, flowing strokes. An owl hieroglyph could have incredibly detailed feathering in its hieroglyphic form, yet in hieratic it is reduced to one flowing movement and looks like a 3.

Certain groups of signs were put together in ligatures, so that they could be written in one or two strokes rather than several separate movements.

While it is true that hieroglyphic styles can be differentiated, they are always going to be the product of teamwork and so the hand of an individual craftsman often cannot be identified except after 73

careful study of hand-painted hieroglyphs. Documents written in hieratic must always be the work of an individual and they preserve all kinds of handwriting. Depending on the type of document, there are some beautiful examples of what might be called a ‘book hand’, such as the Ramesside Papyrus Harris I, which is complete with painted vignettes. There are also some examples of student texts, or simply texts written by a bad scribe, and there is a whole range of material in between. At least these are truly holograph versions of these documents, whoever may have written them. The study of the handwriting (palaeography) is useful in dating texts as there are noticeable differences in styles over time. This is true for any handwritten document, but in Egypt it is particularly useful for documents without a provenance or which have been reused later.

The style of dated documents is studied and the characteristics of the handwriting can be applied to documents of unknown date.

Through this type of study individuals can be recognized and this in turn can have implications for following individual careers and

phs

sometimes state affairs.

ogly

Hier

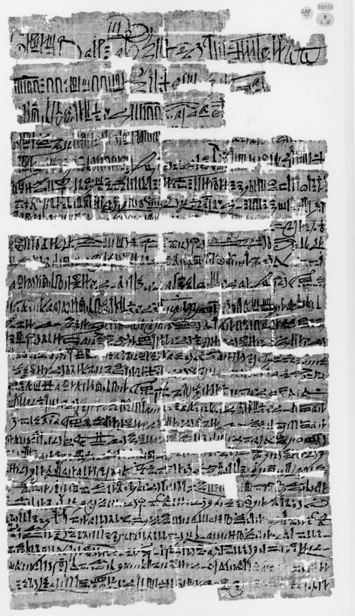

An archive of letters written by the scribe of the tomb Djehutymose and his son Butehamun provides valuable information about the state of affairs in Thebes during the reign of Ramesses XI in the uncertain times at the end of the New Kingdom. As a trusted aide of the generals in charge of Upper Egypt Djehutymose had to travel to Nubia and places within Egypt to report on events there while Butehamun kept management of affairs at Thebes. The letter below from Year 10 of the Renaissance Period opens with wishes for the blessings of the Theban gods on the General Piankh. There is a report on the receipt and reading of the general’s last letter, then a report on the fact that the Theban contigent was too slow in sending some clothes for Piankh and that his wife suggested Djehutymose deliver them in person to Piankh in Nubia. This domestic-sounding detail actually reveals that Piankh was extremely busy with threatening events in Nubia. The letter concludes with some difficulties over a building commission and the progress of the search for an ancient tomb in the necropolis. The standard greeting 74

15. Hieratic letter of the scribe Butehamun, written from right to left

(P. British Museum, EA 10375). The signs are relatively large for the

greeting at the beginning, then become smaller so that they fit on this

sheet of papyrus.

formulae, such as ‘may Amun bring you back safe and you fill your embrace with Ne (Thebes) and we fill our eyes with the sight of you when you have returned alive, prospering and healthy’, are combined with evocative descriptions such as that of Djehutymose just missing Piankh: ‘He just about died when we reached Ne and he was told you had gone before we had reached our mistress!’

1

Hieratic documents

The range of hieratic documents is enormous, covering every type of document that could be written, including administrative tax accounts, day books recording the workers in the Valley of the Kings and their days off, formal state court records and the attendant investigation reports, land leases, and wills. There are also literary works and stories, poems, hymns, and prayers, dream interpreters’

guides, magical spells, medical texts, and books of literary teachings and etiquette (inadequately called Wisdom Texts). There are temple

phs

inventories, records of the rituals to be carried out in the temple, the

ogly

books of knowledge of the temple, the

Book of That which is in the

Hier

Underworld

(guide book for the afterlife), and other books dealing with the next life. There are letters between individuals, letters to the dead, official letters asking for supplies to be sent to a royal work party, and more treasured letters. One letter written by King Pepi II to an individual called Harkhuf asked him to look after a pygmy he was bringing to the king as a gift. The letter was so valued that Harkhuf had a hieroglyphic version of it inscribed onto his tomb entrance at Aswan. There are surviving receipts and accounts by the million for everything from donkeys to lists of laundry. The modern propensity for the written word is not new. Consider a modern dustbin or recycling bin and its contents from letters to council circulars, shop receipts, written packaging, leaflets, magazines—

their ancient equivalent does exist, but in rarefied circumstances and in particular conditions.

Masses of these documents come from the village of the workmen who built the tombs of the kings at the Valley of the Kings in 76

Thebes. The inhabitants of the village of Deir el-Medina were very literate by Ancient Egyptian standards. As many of those who lived and worked there had the job of writing and carving hieroglyphs in the tombs and as many were scribes by profession, perhaps to cope with the administrative demands of such a rarefied place, there was an unusually large number of literate people in the village. Their receipts and notes ended up as infill for a huge pit excavated in the New Kingdom and to provide water. The discovery of this pit was like finding a landfill rubbish dump and sifting through the minutiae of a dustbin to piece together bits of individual lives.

The texts survive on flakes of limestone and on fragments of pottery called ostraka (singular ostrakon). Some of these are hand-sized notelets that would have been placed in the palm of the hand of the scribe, fitting there snugly as they were written out. A scribe called Qenherkhopshef is recognizable by his handwriting, great

Scribes an

sprawling hieratic signs, and by the fact that he bashed the edges of his ostraka so that they were blunted and splinters did not break off,

d e

taking part of an important note with them. He and his family also

veryda

had a library containing a varied collection of papyrus books of

y writin

many different kinds, presumably for their own amusement and perhaps to read out to other villagers. From this library came over

g

40 texts including a copy in Qenherkhopshef’s hand of the ‘Battle of Qadesh’, the ‘Story of Horus and Seth’ (a kind of mythological soap opera), ‘The Tale of the Blinding of Truth’, ‘Love Songs’, ‘Extracts from the Maxims of Any’, hymns, recipes against greying hair and baldness, a dream book, official and private letters, and the wills and testaments of Naunakhte.

2

Perhaps more than anything else, the material from the village hints at a vast oral and aural literary tradition of which only a tiny proportion has been preserved. Some of the stories from Egypt are only preserved in a single text such as the earlier Tales of Wonder in Papyrus Westcar, and this too seems to be a story cycle with various episodes which was committed to papyrus by a scribe at one time.

The Demotic cycle of ‘The Story of Petiese, son of Petetum and 70 Other Good and Bad Stories’ begins with the words, ‘The voice 77

which is before Pharaoh’, implying that the stories were intended to be read out before an audience.

3

The Letters of Hekanakht were written in the early years of Senwosret I in Dynasty 12 on behalf of the

ka

-priest Hekanakht.