Hieroglyphs (10 page)

Authors: Penelope Wilson

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #Ancient, #Social Science, #Archaeology, #Art, #Ancient & Classical

Hieroglyp

This is also the case with three-dimensional statuary. A statue of

hs an

a man and his wife shows them seated but they are identified by

d ar

texts, either at the base of the statue or written just behind them.

t

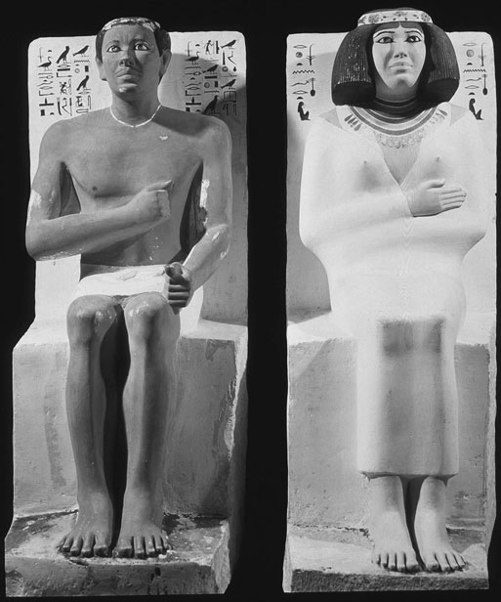

The famous statue of Rahotep and Nofret, for example, has the husband and wife identified by their names written behind them on a back slab. In the case of Nofret, ‘The Beautiful Woman’, her image is identified by her name, with a female seated woman determining sign. The three-dimensional sculpture, however, itself acts as a huge determinative for the tiny piece of text. In the case of Rahotep, the relationship between sculpture and image is even more explicit. His titles and name are also written behind his head but his name does not have the accompanying seated male determinative. In this case, the compact text leads on to the statue itself acting as a Rahotep determinative, personified in stone as an ideal image of a man with his status. His spirit could easily have recognized its home, the image of its earthly body, reading the text, reading the statue, and taking up its residence from where it receives sustenance and revitalizes Rahotep in his next life.

41

phs

ogly

Hier

7. Statue of Rahotep and Nofret, from Medum, Dynasty 4.

Text and image are complementary and although the natural way for Egyptian to be written is from right to left, the pictorial qualities of hieroglyphs mean that the writing has much more flexible, architectural uses. One of the key elements in Egyptian design is the desire for symmetry, and the only way that this can be achieved with texts is by using hieroglyphs. The west wall of the tomb chapel of Werirenptah is now in the British Museum and comes originally from Saqqara, dating to Dynasty 5. It is dominated by two ‘false’

doors which were intended to be the access points to the living 42

world for the

kas

of Werirenptah and his wife, Khentkaues.

Doorways are the entrances into important monuments such as tombs and temples, which are really entrances to different worlds, and so it was important for them to provide the right environment and a clear, pure entrance. The door jambs of the entrance are symmetrical, with the hieroglyphs facing one another on either side of the door. They help to focus attention on the actual door itself and complement the standing figures facing inward. In other entrances, especially in temples, the texts over the doorways were written symmetrically so that they would start in the centre of the door lintel. They read away from one another to the end of the lintel and then continue down the door jambs, still facing each other. This arrangement is aesthetically pleasing and provides a harmonized funnel focused towards the inside of the building or the room.

Hieroglyp

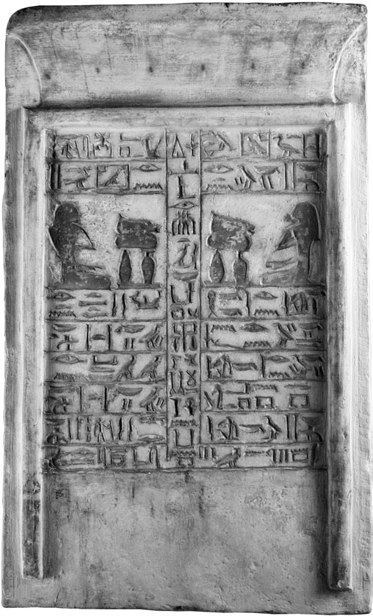

This architectural view and use of hieroglyphs is echoed in the zones and layout of funerary stelae. The limestone stela of the

hs an

Guardian of the Chamber of Kheperka, Seru son of Sat-Hathor, is

d ar

one of many hundreds of thousands made in Ancient Egypt, yet it

t

speaks for all of them. It is rectangular and has a cavetto corniche –

an architectural framing element found at the tops of doors and walls. The stela is divided in two by a vertical line of hieroglyphs containing the offering formula and reading in the normal direction from right to left. Both sides of the text are two symmetrical scenes.

There are two horizontal lines of text on the right reading from left to right; on the left from right to left; then come two figures in silhouette facing each other inward, a man on the left (Seru) and a woman on the right (his mother, Sat-Hathor); then there are another six lines of text reading towards the edge of the stela. The two sides form the door leaves of a door designed to swing inwards.

The figures would then both be inside the tomb, inside the realm of the dead, and would occupy their proper position. The hieroglyphic text would direct the offerer or visitor towards them, but turns out to be something different from the funerary formula down the centre, for it is a list of family members. This is a family monument 43

8. Stela of Seru in the Oriental Museum, University of Durham. Dated to

Dynasty 12.

with as many people as possible mentioned on this one piece of stone so that they can have existence in the afterlife.

In looking at a wall covered in scenes and texts the most striking impression is that everything is well ordered in lines called registers. The scenes and texts are all written in straight lines. This may derive from the riverine nature of life in Egypt. The most common place to travel in Egypt would have been alongside or on the River Nile. From this perspective the whole world is ordered in horizontal registers: the river itself at the bottom, then a line of river bank, then a cultivated strip, then the trees, then the desert, and above the terrestrial sphere the sky. If this is viewed in the Egyptian way as a flat surface, then all of these elements are not arranged by perspective, one in front of the other, but in horizontal registers, one above the other. Within this context the lines of text fit well into scenes, interacting with the images depicted there or framing whole

Hieroglyp

scenes. Most figures in a scene are accompanied by a line of hieroglyphs, usually identifying the person shown and often

hs an

containing the words the figure is saying. The ‘speech-balloon’

d ar

always reads towards the face of the person speaking the words. In a

t

temple, the king ‘speaks’ the offering ritual to the god of the temple and the gods reply with the appropriate reward speech. Even if the orientation of the texts at this point in the temple is left to right (for example, entering a room), the speech can be turned against this direction (retrograde) in order to suit a figure of the king coming through the door and speaking.

1

In more informal scenes the hieroglyphs record the more everyday speeches of ordinary people going about their daily business and reflect the positions of people as they face each other. Busy agricultural scenes in the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep record the words of agricultural workers, with the hieroglyphs acting like speech balloons in a cartoon strip. They provide a script to ensure that everyone in the scenes performs their role correctly, so that the tomb owner is not deprived of anything in his next life. The scenes may be to provide all the agricultural produce from seed to processed foodstuff in case the real offerings fail in the years ahead. Anybody who is anybody is 45

phs

ogly

9. Catching fish in a trap, Tomb of Kagemni, Dynasty 5, Saqqara

Hier

Necropolis.

named so that they can carry out their function. The scenes and text provide a memory of this life too, however idealized, so that the status of the tomb owners is also maintained and assured.

In the Tomb of Kagemni a boatman puts his fish trap into the water, hoping to land one of the many fish in the shallow waters. His words,

snHw n pr-Dt

‘Fish-trapping for the House of Eternity’, leave no doubt as to the eventual destination of the fish. If all the hieroglyphs could be imagined as sound, the tombs would be full of noise, with the chatter of hundreds of people.

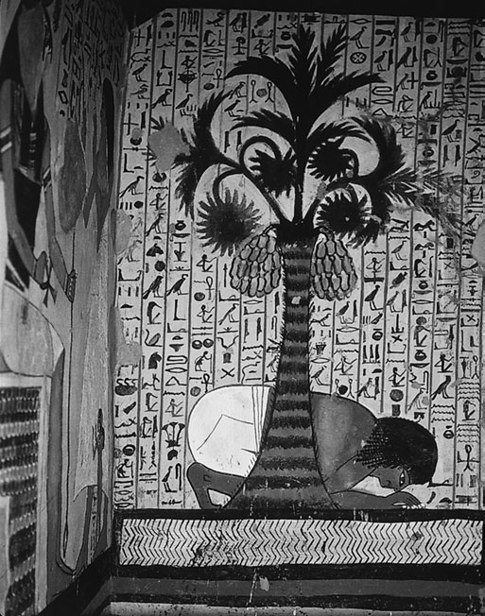

Perhaps in an even clearer illustration of words as pictures, the prayer for ‘Drinking Water’ in the afterlife is shown in the Tomb of Pashedu as hieroglyphic wall decoration, with the hieroglyphs of the prayer filling the air as his words float up into the air around him.

46

10. Pashedu in his tomb at Deir el Medina, Thebes, from Dynasty 19.

The words of his prayer float up into the air around him like a designer

wallpaper.