Heroes for My Son (10 page)

Authors: Brad Meltzer

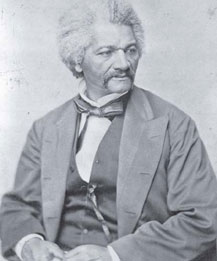

Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery at the age of twenty. In his speeches and books, he became one of America's foremost orators, teaching whites, blacks, and an entire nation about the injustice of slavery, while also fighting for equality for all people.

Â

Â

S

ome arm themselves with guns.

Some with knives.

Some with bombs.

Â

Born into slavery, Frederick Douglass armed himself with something far more dangerous.

Â

His masters whipped him for it.

They used a hickory stick to beat him over the head.

They starved him until he collapsed.

But none of those punishments stopped him from finding itâthe greatest, most powerful weapon ever created:

Â

The ability to read.

And the bravery to share his story.

Â

At sixteen, Frederick Douglass began teachingâillegally showing slaves how to read and write.

By twenty, he'd escaped to New York, where he found an even larger audience.

Â

In the end, the other side had power.

Frederick Douglass just had words.

Â

They didn't stand a chance.

*

If there is no struggle, there is no progress.

âFrederick Douglass

When the engines went dead, Captain Chesley Sullenberger kept his calm and saved 155 lives by gently landing US Airways Flight 1549 in the Hudson River.

Â

Â

I

t's one thing to have all the piloting experience, to know what to do when both engines on the airplane fail, to take an Airbus that's not designed for gliding and do exactly that because you're also a certified glider pilot.

Â

It's another thing to take all that experience and, as the plane is plummeting from the sky, still remain completely calm.

Â

And it's yet another thingâwhile the plane is sinking in the Hudson River and drifting with the currentâto walk the aisle of the cabin, making sure all the passengers get out before you do.

And then to walk that aisle again, just to be sure.

Â

But when it was all finished and every TV camera came to your front doorâto humbly shrug and say you were just doing your job?

Â

That wasn't just bravery.

That was honor.

*

Â

SULLENBERGER:

We're going to be in the Hudson.

Â

AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL:

I'm sorryâsay again, Captain?

One way of looking at this might be that for forty-two years I've been making small, regular deposits in this bank of experience: education and training. And on January 15 the balance was sufficient so that I could make a very large withdrawal.

âChesley Sullenberger

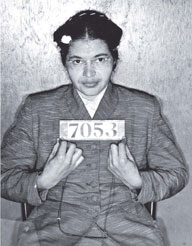

On a crowded bus in 1955, African American seamstress Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man. Her act of defiance ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which lasted 381 days. Then public busing segregation came to an end. And a movement began.

Â

Â

Y

es, she was tired.

Â

She had grown up with the KKK riding past her house, her grandfather standing guard with the shotgun.

Â

She had endured seeing her school burn downâtwice.

Â

She had faced this bus driver before, when he left her to walk five miles in the rain because she sat down in the white section to pick up her purse.

Â

She had lived with injustice her entire life.

Â

Yes, she was tired.

Â

But it wasn't the kind of

tired

that came from aching feet.

Â

“The only tired I was was tired of giving in.”

Â

So when the bus driver motioned to her to stand and give her seat away to a white person, the seamstress from Montgomery, Alabama, refused.

Â

“Well, I'm going to have you arrested,” the bus driver said.

Â

Rosa Parks calmly replied, “You may go on and do so.”

Â

For violating Chapter 6, Section 11, of the Montgomery City Code, Rosa Parks went to jail.

Â

For standing up for herselfâby sitting downâRosa Parks ignited a movement.

*

All I was doing was trying to get home from work.

âRosa Parks

Despite muscle spasms and broken bones, New York Yankee Lou Gehrig played in 2,130 consecutive games. In thirteen of those seasons, he scored 100 runs and hit 100 RBI. His batting average of .361 in seven World Series brought the Yankees six titles. It took a debilitating and fatal disease to take him off the field, and even then he wasn't beat.

Â

Â

F

or thirteen seasons, Lou Gehrig never missed a single game.

Think of it.

Think of what happens over thirteen years.

Â

He didn't miss a game when he was sick.

Or when he was tired, or bored, or not feeling right.

Â

Not when he was under the weather, or drained, or just wanted to take a day for himself.

Not when he broke his thumb.

Or his toe.

Or when he suffered the seventeen other “healed” fractures that they found in just his hand and that they never knew about because he never complained.

Â

For thirteen seasons, for more than two thousand games in a row,

Lou Gehrig showed up,

because he never wanted to let us down.

Â

The only thing that stopped him?

The fatal disease that once caused his back to spasm so badly, he had to be carried off the field.

Â

They called Lou Gehrig “the Iron Horse.”

But he wasn't made of iron.

Â

He was made like us.

Â

He just didn't let that stop him.

*

I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the Earth. And I might have been given a bad break, but I've got an awful lot to live for.

âLou Gehrig, farewell speech, July 4, 1939, Yankee Stadium

Â

Â

I

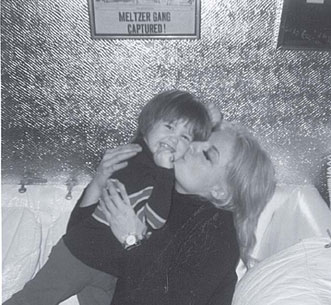

t was the worst day of my professional life.

Â

My publisher was shutting down, and we had no idea if another publisher would take over my contract.

Â

This was terrifying to me. I was wracked with fear, feeling like I was watching my career deteriorate.

Â

But as I shared my fears with my mother, her reaction was instantaneous: “I'd love you if you were a garbage man.”

Â

It wasn't anything she practiced. It was just her honest feelings at that moment.

Â

To this day,

every

day that I sit down to write, I say those words to myselfâ“I'd love you if you were a garbage man”âsoaking in the purity and selflessness of that love from my mother.

Â

Her name was Teri Meltzer. And, Theo, she's the woman you're named after.

H

Now you'll understand how I love you.

âTeri Meltzer, on the birth of each of my children

Not everyone is nice like that.

âThe receptionist in my mom's doctor's office, when she heard that my mom had died from breast cancer. Always remember: the truth is what people say behind your back.