Henry IV (5 page)

Authors: Chris Given-Wilson

Nowhere did the aspiration of fifteenth-century rulers to act as ‘emperors in their own kingdoms’ come closer to being realized than in England. This was a functioning state, a vehicle for powerful, potentially predatory, kingship. On the other hand, its dependence on active and cooperative kingship and the power which it invested in the person of the monarch was also its Achilles heel, for it relied disproportionately on the aptitude of each king to make it function in a way that was acceptable to the polity, and aptitude was not something that the lottery of heredity could guarantee.

1

La Chronique d'Enguerran de Monstrelet 1400–1444

, ed. L. Douët-d'Arcq (SHF, 6 vols, Paris, 1858), ii.338–9.

2

Below (Epilogue), pp. 535–41.

3

SAC II

, 618–19;

Usk

, 242–3; BL Add. Ms 35,295, fo. 262r; C. Kingsford,

English Historical Literature in the Fifteenth Century

(Oxford, 1913), 277;

Monstrelet

, ii.337.

4

J. Clark, ‘Thomas Walsingham Reconsidered: Books and Learning at Late Medieval St Albans’,

Speculum

77 (2002), 832–60, questions Walsingham's authorship of the whole of the St Albans chronicle.

5

The phrase was coined by Edward Hall,

The Union of the two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancastre and York

(1542).

6

Below (Epilogue), pp. 538–9.

7

A. Brown,

The Governance of Late Medieval England 1272–1461

(London, 1989), 52.

8

The Hanseatic and Lombard leagues and the Swiss confederation are the most striking examples; leagues of towns were especially effective in the Empire.

9

See, for example, R. Davies,

Lords and Lordship in the British Isles, passim

; C. Given-Wilson, ‘The King and the Gentry in Fourteenth-Century England’,

TRHS

37 (1987), 87–102. For an analysis of this theme in a Europe-wide context, see J. Watts,

The Making of Polities: Europe 1300–1500

(Cambridge, 2009); for England, see G. Harriss, ‘Political Society and the Growth of Government in Late Medieval England’,

Past and Present

138 (1993), 28–57, and G. Harriss,

Shaping the Nation: England 1360–1461

(Oxford, 2005).

Part One

THE GREAT DUCHY 1267–1399

Chapter 1

THE HOUSE OF LANCASTER AND THE CROWN (1267–1367)

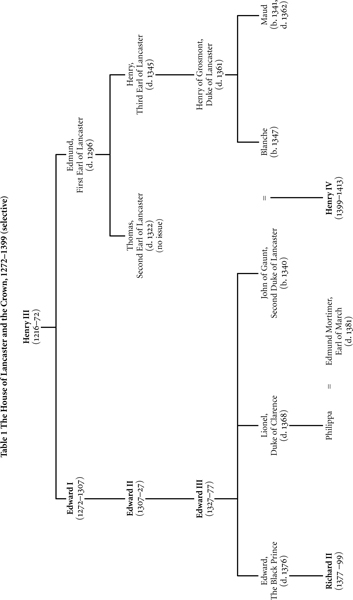

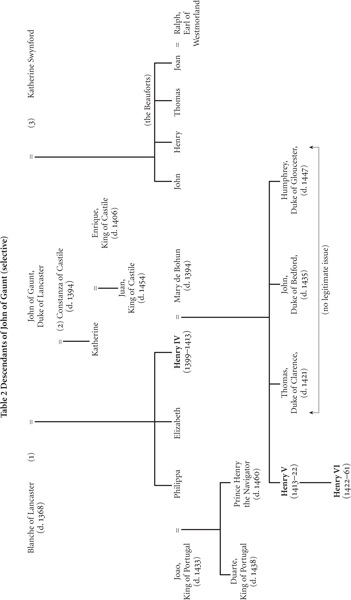

The future King Henry IV of England was born on or around 15 April 1367 at Bolingbroke castle, fifteen miles north of Boston on the southern edge of the Lincolnshire wolds, the fifth-born child of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, fourth son of King Edward III, and Blanche, only surviving daughter of Henry of Grosmont, first duke of Lancaster (d. 1361). However, since his older brothers John and Edward had died as infants and his remaining siblings were both girls, he was, from the moment of his birth, his parents' sole and undisputed heir, and the patrimony which he stood to inherit was the greatest in England bar the crown.

1

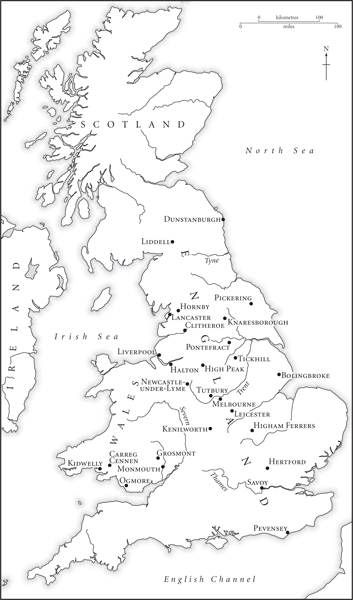

A century old in the year of Henry's birth, the Lancastrian inheritance had, like most noble estates, been assembled through a combination of aggressive acquisition, royal favour and the misfortunes of others. The prerequisite for its creation was the battle of Evesham in August 1265, at which the baronial coalition that had challenged Henry III's rule for the previous seven years was defeated and its leader Simon de Montfort, earl of Leicester, killed. Two months later the bulk of Montfort's lands, including the castle and honour of Leicester, were granted by the king to his younger son Edmund ‘Crouchback’, who in 1267 became earl of Leicester. Meanwhile Robert de Ferrers, earl of Derby, who had not been at Evesham but had previously opposed the king, rebelled once more and was defeated at Chesterfield in May 1266; his lands too were granted to Edmund, and in 1267 Henry III also granted his son the castle, honour and county of Lancaster, and the honour of Pickering in Yorkshire.

2

Two years on from Evesham, therefore,

the foundations of the future greatness of the house of Lancaster had been laid and the disposition of its principal holdings established. Leicester, Kenilworth in Warwickshire (also a former de Montfort castle), and Tutbury in Staffordshire (the Ferrers

caput

) for long remained the principal Lancastrian residences in the Midlands; Pickering marked the first stage of what would later become a dominant, if never unchallenged, interest in Yorkshire; while Lancaster provided Edmund and his descendants with a consolidated block of lands and rights which would one day lead to its elevation to the status of Duchy and County Palatine – as well, of course, as giving them the title by which they would almost invariably be designated. Why that was the case – why, that is, they came to be known as earls of Lancaster rather than of Leicester or Derby – was probably because their claims to the latter two earldoms were less secure, founded as they were upon civil war, disinheritance and legal chicanery. Those whom they supplanted, such as the Ferrers – still peers of parliament even if no longer earls – did not forget this, and continued to nurture their hopes and advance their claims.

3

The annual value of the lands which Edmund passed on to his son Thomas at his death in 1296 was in the region of £4,500, but more valuable still was Thomas's marriage, arranged by Edmund in 1294, to Alice, daughter and heiress of Henry de Lacy, earl of Lincoln, whose inheritance included the lands of the earldom of Salisbury and was worth a further £6,500 per annum. Thus, following de Lacy's death in 1311, Thomas became the holder of a landed estate the size and value of which – some £11,000 per annum – made him incomparably the richest and most powerful lord in England after the king.

4

Especially useful to Thomas was the fact that the geographical distribution of the Lacy lands tended to augment Lancastrian power in areas where it was already strong, as well as

to bring in new, often contiguous, centres of wealth and influence. The honours of Clitheroe and Halton were added to Thomas's sizeable possessions in Lancashire; the castle and rich honour of Pontefract significantly expanded his interests in Yorkshire, while the even richer honour of Bolingbroke in Lincolnshire extended his already dominant position in the Midlands towards the North Sea. The lordship of Denbigh in North Wales, also acquired from his father-in-law, was followed seven years later by further substantial lands in the Welsh Marches, for in 1318, following a dispute with John de Warenne, earl of Surrey (who had abducted Thomas's wife Alice the previous year), Warenne was forced to grant him all his lands in North Wales and Yorkshire, as well as some in East Anglia, in return for a number of considerably less valuable manors in Wiltshire, Somerset and Dorset which had come to him through the Lacy inheritance.

5

Such an unequal exchange, the product of the political circumstances of the moment, might be enforceable in the short term but, like the disinheritance of Robert de Ferrers, was unlikely to remain uncontested. Edmund's accumulation of lands and titles had been his reward for consistent loyalty to the crown; so too had the favours shown to Thomas during his teens and twenties. However, from the winter of 1308–9 (when he was aged thirty), Thomas moved into opposition to the new king, Edward II, a stance which he maintained for the rest of his life, the mistrust and hatred between the two cousins growing ever deeper until, in the autumn of 1321, the civil war which had threatened periodically during the previous decade eventually erupted. The upshot was catastrophic: captured at the battle of Boroughbridge, Thomas was taken to his favourite castle of Pontefract – where, it was rumoured, he had planned to imprison the king had he prevailed – put on trial and, on 22 March 1322, led out to a hillock just below the castle walls and beheaded. Convicted of treason, he also forfeited all his lands and chattels. The Lancastrian inheritance was no more: decapitated and dismembered, it was parcelled out between the king and his supporters, chief among them Lancaster's bitterest enemies, the two Hugh Despensers, father and son.

The road to recovery was not as slow as it might have been, but it required both persistence and good fortune, especially since Thomas had left no son to work his way back into royal favour. His heir was his brother Henry, who had not taken part in the revolt of 1321–2. Yet, although he was restored to the earldom of Leicester in 1324, Henry had to wait until the overthrow of Edward II and the Despensers in 1326–7 before he could

embark with confidence on the process of claiming his brother's inheritance. Even then there were pitfalls to be negotiated: the regime which took power following Edward II's deposition, led by Queen Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer, proved little better than its predecessor, so that once more an earl of Lancaster (to which title Henry had been restored at the deposition) found himself in opposition to the crown, or at least to those who now governed on its behalf. However, once the eighteen-year-old Edward III asserted his personal authority, did away with Mortimer in November 1330, and forced his mother into political retirement, relations between the crown and the nobility improved markedly, so that for the next thirty years, first under Earl Henry and then, after his death in 1345, under his son Henry of Grosmont, the house of Lancaster reverted to what it had been during the first forty years of its existence: a political and military bloc, the power of which was not to be feared but rather to be augmented by the king, and one of the chief buttresses of the crown during the harmonious central years of Edward III's reign.

Map 1

Principle holdings of the duchy of Lancaster

This did not mean, however, that everything once held by Earl Thomas was regained. John de Warenne's lands in Yorkshire were returned to him in 1328, never again to pass into Lancastrian hands, while the manors in Wiltshire, Somerset and Dorset which Thomas had granted to Warenne in exchange became the subject of a prolonged dispute between the house of Lancaster and the Montague family, for whom the earldom of Salisbury was revived in 1337. The title and many of the lands of the earldom of Lincoln, along with Pontefract and Clitheroe, were not regained until after the childless death of Alice de Lacy in 1348. By now, the pace of Lancastrian recovery was quickening, lubricated by the close friendship between Henry of Grosmont and Edward III and his extensive diplomatic and military career in royal service.

6

In 1337, while his father was still alive (though by now largely incapacitated by blindness), Grosmont was created earl of Derby, the first member of the Lancastrian line to assume that title; by 1349, he could style himself earl of Lancaster, Derby, Leicester and Lincoln, as well as steward of England.

7

Yet more dazzling honours still awaited him: on 6 March 1351, as a sign of his pre-eminence among the English nobility, and in order to enhance his status as a diplomat on the European stage, he was elevated to the dukedom of Lancaster, only the second person ever to hold an English dukedom (the Black Prince, Edward III's eldest son and heir, having been created duke of Cornwall in 1337). In itself, the title

of duke was honorific, but Edward III simultaneously declared Lancashire to be a county palatine, in effect devolving the royal administration within the county into Henry's hands and creating an enclave in which for most practical purposes the duke could act as sovereign: a county, in contemporary parlance, in which the king's writ did not run. The honour done to Henry was, and was meant to be, exceptional. It also had financial implications: although the king retained the right to impose taxes in Lancashire as in the rest of the kingdom, the profits of justice and routine administration now went directly into the duke's coffers. Thus, whereas his father's landed income in the early 1330s had amounted to about £5,500 per annum – only about half of what Earl Thomas had enjoyed – by the time Duke Henry died in March 1361, his income from his lands in England and Wales was in the region of £8,380 per annum.

8

Recovery from the disaster of 1322 had not been complete, but it had been substantial. Once again, however, the future of the inheritance was under threat: not, on this occasion, because of political miscalculation, but because Henry went to his grave without having fathered a son.