Henry IV (16 page)

Authors: Chris Given-Wilson

Map 2

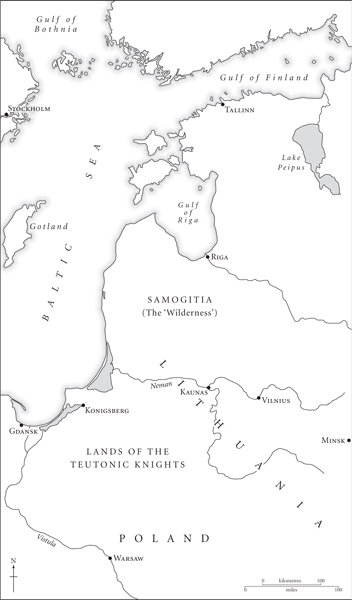

Crusading in the Baltic

Henry now faced the prospect of two to three months of inactivity before the frost made the boggy Wilderness tracks passable once more after the autumn rains.

27

He certainly hoped to campaign again, and on 27 January Richard II wrote at his request to Wladyslaw Jogailo asking for permission for Henry to travel more widely, but what his plan was is not clear,

28

and in the event there was no winter

reyse

, so Henry and his retinue remained at Königsberg until 9 February 1391. It was not a time of hardship. There was plenty of good food, wine and beer to be had; there was regular jousting, hunting and hawking; beaver and marten fur cloaks were bought against the cold; Henry's silver dishes were painted with shields of

his arms, and large amounts of fine cloth were purchased, some of it from an English merchant called John Squirrel resident at Königsberg; minstrels, tumblers and dicing provided entertainment. There were also reasons for celebration, for in November news arrived from England of the safe delivery of Henry's fourth son, Humphrey.

29

Naturally it was also important for Henry to advertise his Christianity, which he did by distributing alms to paupers, prisoners and friars, and by capturing or purchasing a number of Lithuanian women and children who were taken back to Königsberg to be converted.

30

The letter describing Henry's exploits which reached England was careful to emphasize this, stating that 11,500 Lithuanian prisoners had been taken back to Prussia or Livonia ‘to be made into Christians’.

31

This was, after all, the object of the exercise.

In early February Henry and his household left for Gdansk, where they spent the next six weeks enjoying the amenities and provisions on offer in this vibrant Hanseatic port, the largest and wealthiest town in the eastern Baltic, and preparing for the return journey.

32

As before, two ships were required, both skippered by Germans; three dozen chickens were taken aboard to be fed to the falcons which Henry had recently been given by Conrad von Wallenrod, the Grand-Master of the Teutonic Order in Prussia (he had also been given three young bears and perhaps even an elk).

33

The return journey took a month, reaching Kingston-upon-Hull on 30 April 1391. The first thing Henry did was to make a pilgrimage to the

tomb of John de Thwing, prior of Bridlington (d. 1379), whose canonization he would later support, while his baggage was taken to Bolingbroke where he arrived on 13 May to be reunited with his family.

34

Seventeen years later, in conversation with the Hanseatic envoy Arndt von Dassel, Henry recalled fondly his time in Prussia – his ‘gadling days’ – when he had led three hundred men (a pardonable exaggeration) as far as the ‘sacred city’ of Vilnius before the onset of winter drove them back to Königsberg, where the Grand-Master's own physician had tended him through a serious illness. He was, he declared, a child of Prussia, and there was no land apart from England that he would rather serve.

35

Diplomatic niceties apart, he might well have felt nostalgic: for a young man who had barely been out of England before, he had created a fine impression on the international stage. English chroniclers declared that ‘his pre-eminent success brought joy to all Christians’ and that he had ‘fought with the enemies of Christ's Cross in such a way as to suggest that nothing meant more to him than to avenge the dishonour of the Crucifix’, so that ‘his name was on everyone's lips’.

36

If this was John of Gaunt seeking to carve out his son's place in history, he seems to have succeeded.

37

Yet it was not just the English who lauded Henry's deeds. The Prussian chronicler John von Posilge also praised Henry's performance at the siege of Vilnius, claiming that he fought most manfully (

gar menlich

) and that it was his perseverance which led to the outlying fort being taken.

38

Few qualities were admired more than manliness, but Richard II had difficulty in persuading contemporaries that he possessed it, however hard he tried.

39

He could organize tournaments – as he did at Smithfield in October 1390, during Henry's absence – but unlike his father, his grandfather and his cousin, he was not a man who fought real battles.

40

Richard never acquired the chivalric reputation that Henry did, and it piqued him: Henry, after all, had

fewer responsibilities. Nor could he have set about the business of acquiring a reputation without his father's money behind him: the cost of his crusade was £4,360, of which £3,542 came from Gaunt, enabling Henry in turn to demonstrate the largesse to his hosts and companions that was expected of him.

41

Doubtless Gaunt considered it money well spent.

Backlit by this glow of chivalric ardour, Henry's fifteen months in England, from May 1391 to July 1392, were the apogee of his gilded youth. He jousted on at least four occasions: at Brambletye in early July 1391, at Waltham in early October, at Hertford around Christmas and at Kennington on some unspecified date. For each of the first two he bought eighteen new lances in addition to other weaponry, armour and harness, some of it from the famous metal workshops of Milan.

42

His taste for spectacle and desire to advertise his wealth and status were the equal of any noble of his time, as witness the £740 which he spent on drapery, mercery, embroidery, furs and jewels during this period.

43

New suits and mantles of silk, satin, velvet or brocade for almost every occasion were made up by his tailor John Dyndon, lined with miniver or ermine by his pelterer William Jakes, and embroidered by his broderer Peter Swan with intricate and costly fringes, sleeves and collars of lace, tissue, taffeta, spangles or gold thread. The livery devices adorning them grew ever more elaborate. One of Henry's velvet mantles had sleeves embroidered with a design of Saint John's wort and his motto ‘Soveyne Vous de Moy’ (forget me not). Chevrons, wheels, mulberries and flowers were worked into the designs. One of his belts had silver-gilt leaves and fronds hanging from it, weighing nine and half troy marks (just over six pounds). Another gown had sleeves into which were sewn 320 silver-gilt leaves, each one reading ‘Soveyne Vous de Moy’. A golden brooch engraved with ‘Sanz mal penser’ (think no evil) echoed the

‘Honi soit qui mal y pense’ of the Order of the Garter. A silver collar encrusted with eight roundels, each one enclosing a Lancastrian S and the figure of a swan (the livery badge of the Bohuns), cost £23; another, costing £17, had golden locks and keys hanging from it, while one of his brooches was made in the shape of a large letter H on each side of a balas ruby. Friends and followers were also encouraged to advertise his largesse and status: thirty silver-gilt collars of Henry's livery were lined with satin before being distributed to his retainers, while his jousting and crusading companions, Sir Robert Ferrers, Sir John Malet and the Bohemian Herr Hans, each received entire satin livery suits.

44

To his wife, Henry sent a garter with a clasp in the shape of a golden hart set in white enamel with a collar costing £9; Mary responded by sending him six yards of blue velvet. For the christening of their daughter Blanche at Peterborough in 1392, all four of their sons had new shirts of cloth from Champagne, and the elder boys, Henry and Thomas, received silver-gilt Lancastrian livery collars.

By the summer of 1392, however, Henry was ready to return to Prussia. Embarking on 24 July at Heacham in Norfolk, he landed just north of Gdansk on 10 August and reached Königsberg on 2 September, only to discover that Prince Vitold was in the process of making his peace with Jogailo and had dismissed all the Western crusaders.

45

Making a virtue of necessity, therefore, Henry arranged for most of the 150–200 retainers and servants who had accompanied him from England to return home, sent a messenger to his father asking for an exchange of money to be arranged for him at Venice and, accompanied by about fifty friends and servants, set out on 22 September for the medieval equivalent of what would later become known as the grand tour.

Henry's itinerary took him first to Frankfurt-am-Oder, then to Prague, where his party rested for eleven days (13–24 October) before moving on to Vienna for the nights of 4–7 November. Crossing the Julian Alps, he reached Venice at the beginning of December, hired a galley from the Venetian Senate, and on 23 December set sail for Jaffa with about forty servants.

Sailing via Zara, Corfu, Modon in the Morea and Rhodes, he arrived in the Holy Land in late January and remained there ten days, visiting the Holy Sepulchre and probably the Mount of Olives as well. By 6 February he was back in Jaffa, whence he sailed via Cyprus and Rhodes back to Venice, where he arrived on 20 March. He stayed in Venice for Easter, which fell on 6 April, and then a further two weeks at Treviso (12–28 April) preparing for the return journey to England. Moving at a leisurely pace through Padua, Vicenza and Verona, he spent three or four days in Milan (13–16 May), reached Turin on 21 May, and five days later passed over the summit of Mont Cenis – where, a dozen years later, the chronicler Adam Usk would describe being ‘almost frozen to death by the snow’, even in the middle of summer – and into Savoy.

46

From here Henry's route took him through Burgundy and Champagne to Paris, barely passing more than one night anywhere until he reached the French capital on 22 June.

47

He crossed from Calais to Dover on 29 June and reached London on 5 July 1393.

Henry travelled in great style. Whenever he moved on, heralds and harbingers were sent ahead to proclaim his imminence and requisition supplies and lodgings. Wherever he stayed more than a night or two, local artisans were hired to paint escutcheons of his arms at the door. Riding his favoured white courser, preceded by Thomas his trumpeter,

48

attended by two dozen knights and esquires on horseback with a baggage train bringing up the rear, his entourage generally covered between fifteen and twenty miles a day but could move faster if required: the 375 miles from Vienna to Treviso took just fourteen days, an average of twenty-seven miles a day, including crossing the Julian Alps by the Predil pass.

49

Local guides and porters were hired when necessary, and between Portogruaro and Venice nine men had to break the ice along the road to ease the convoy's passage.

50

Henry was also accompanied by a small but growing menagerie of curious and exotic beasts: he acquired an ostrich in Bohemia, a ‘popinjay’ (parrot) in Italy as a gift for his wife Mary, and a leopard, probably a present from the king of Cyprus. For the sea-journey from

Cyprus to Venice, the leopard had its own cabin and mat to lie on and ate a third of a sheep each day.

51

Of more lasting value were the contacts established by Henry with European princes, prelates and merchants. At Prague, he spent three days staying with the Holy Roman Emperor Wenzel at his country palace at Bettlern; at Vienna, he was the guest of Albert of Hapsburg, duke of Austria, and paid a visit to Sigismund, king of Hungary, whose palace was on the other side of the Danube.

52

When the Venetian Senate heard that Henry was on his way it voted 360 ducats of public money for his accommodation and put a state galley at his disposal, and on his return from the Holy Land the Grand Council allocated a further one hundred gold ducats for a reception in his honour.

53

At Rhodes Henry was hosted in the castle by the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller and at Cyprus by King James of Lusignan. He met the patriarch of Friuli and the archbishop of Milan; while at Milan he was also entertained by the mighty Gian Galeazzo Visconti, count of Vertus and lord (later duke) of Milan, who showed him the tombs of St Augustine, Boethius, and Henry's own uncle Lionel of Clarence.

54

In Paris he was shown around the city by the dukes of Berry and Burgundy. Henry also had regular dealings with some of Europe's foremost banking houses. Thanks to his father having deposited £1,333 at Leicester with Matteo, a partner in the Florentine Alberti bank, Henry was able to withdraw 8,888 Venetian ducats from the Alberti offices at Venice at the beginning of February 1393. Lucchese and Lombard bankers provided a further 4,095 ducats, again in return for Gaunt's deposits, in April and May. International religious orders could also double as banking houses: the Prior of the Hospitallers provided Henry with 1,700 ducats at Venice in exchange for an equivalent sum in sterling made over to the Order in England by Gaunt.

55

Having already availed himself of the

services of the Hanseatic merchants in Prussia, Henry's dealings with Italian financiers, who provided the motor for the southern European economy, gave him further connections which he would later find useful. With his reputation as a jouster and crusader preceding him, his

courtoisie

and largesse to recommend him,

56

and a pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulchre furnishing an impeccable pretext for his travels, Henry was feted wherever he went. Six years later, Gian Galeazzo's cousin Lucia would declare that if she could have married Henry, she would have waited ‘to the very end of her life, even if she knew that she would die three days after the marriage’. Lucia did come to England, though not to marry Henry. In January 1407 she married Edmund, earl of Kent, and although he was killed in the following year she remained in England until her death in 1424.

57