Hell (15 page)

After

thirty-seven years of marriage I know Mary so well that I can hear the strain

of the last few weeks in her voice. I recall

Ms

Roberts’ words the first time we met: ‘It can be just as traumatic for your

immediate family on the outside, as it is for you on the inside.’ My two-pound

BT

phonecard

is about to run out, but not before I

tell her that she’s a veritable Portia and I am no Brutus.

The moment I

put the phone down, I find another lifer, Colin (GBH), standing by my side. He

wants to have a word about his application to do an external degree at Ruskin

College, Oxford. I have already had several chats with Colin, and he makes an

interesting case study. In his youth (he’s now

thirtyfive

)

,

he was a complete wastrel and

tearaway

,

which included a period of being a professional football hooligan. In fact, he

has written a fascinating piece on the subject, in which he now admits that he

is ashamed of what he got up to. Colin has been in and out of jail for most of

his adult life, and even when he’s inside, he feels it is nothing less than his

duty to take the occasional swing at a prison officer. This always ends with a

spell in segregation and time being added to his sentence. On one occasion he

even lost a couple of teeth, which you can’t miss whenever he grins.

‘That’s

history,’ he tells me, because he now has a purpose. He wants to leave prison

with a degree, and qualifications that will ensure he gets a real job. There is

no doubt about his ability. Colin is articulate and bright, and having read his

essays and literary criticism, I have no doubt that if he wants to sit for a

degree,

it’s

well within his grasp.

And this is a

man who couldn’t read or write before he entered prison. I have a real go at

him, assuring him that he’s clever enough to take a degree and to get on with

it. I start

pummelling

him on the chest as if he was

a punch bag. He beams over to the duty officer seated behind the desk at the

far end of the room.

‘

Mr

King, this prisoner is bullying me,’ says Colin, in a

plaintive voice.

The officer smiles.

‘What have you been saying to him,

Archer?’

I repeat the

conversation word for word.

‘Quite agree

with you, Archer,’ he says, and returns to reading the

Sun

Supper.

Vegetarian fingers, overcooked and

greasy, peas that are glued together, and a plastic mug of Highland Spring

(49p).

I’ve just

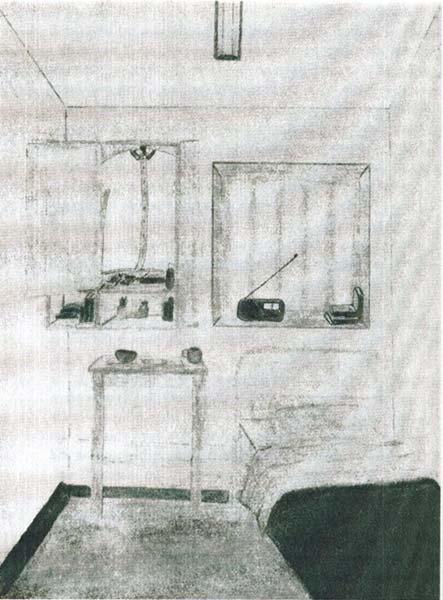

finished checking over my script for the day when my cell door is opened by an

officer. Fletch is standing in the doorway and asks if he can join me for a moment,

which I welcome. He takes a seat on the end of the bed, and I offer him a mug

of blackcurrant juice. Fletch reminds me that he’s a Listener, and adds that

he’s there if I need him.

The Listeners

Who are they?

How do I

contact them?

How do I know I

can trust them?

Listeners are

inmates, just as you are, who have been trained by the

Samaritans

in both suicide awareness and befriending skills.

You can talk to

a Listener about anything in complete confidence, just as you would a

Samaritan.

Everything you say is treated

with confidentiality.

Listeners are

rarely shocked and

you don’t have to be

suicidal

to talk to one. If you have any worries or concerns, however great

or small,

they are there for you.

If

you have concerns about a friend or cellmate and feel unable to approach a

member of the spur staff or healthcare team, then please tell a Listener in

confidence.

It is not grassing and it

may save a life.

Listeners are easy to contact. Their names

are displayed on orange cards on their cell doors and on most notice boards

throughout the House-Blocks or ask any member of the spur staff.

Listeners are

all bound by a code of

confidentiality

that

doesn’t only run from House...

Block to

House-Block but also through a great number of Prisons throughout the country.

Any breach of that confidentiality would cause irreparable damage to the

benefits achieved, and because of this code Listeners are now as firmly

established as your cell door.

He then begins

to explain the role of Listeners and how they came into existence after a

fifteen-year-old boy hanged

himself

in a Cardiff jail

some ten years ago. He passes me a single sheet of paper that explains their

guidelines

.

Among

Fletch’s

responsibilities is to spot potential

bullies and – perhaps more important – potential victims, as most victims are

too frightened to give you a name because they fear revenge at a later date,

either inside or outside of prison I ask him to share some examples with me.

He tells me

that there are two heroin addicts on the spur and although he won’t name them,

it’s hard not to notice that a couple of the younger lifers on the ground floor

have needle tracks up and down their arms. One of them is only nineteen and has

tried to take his own life twice, first with an overdose, and then later when

he attempted to cut his wrist with a razor.

‘We got there

just in time,’ says Fletch.

‘After that,

the boy was billeted with me for five weeks.’

Fletch feels

it’s also vitally important to have a good working relationship with the prison

staff – he doesn’t call them screws or kangaroos – otherwise the system just

can’t work. He admits there will always be an impenetrable barrier, which he

describes as the iron door, but he has done his best to break this down by

forming a prison committee of three inmates and three officers who meet once a

month to discuss each other’s problems. He says with some considerable pride

that there hasn’t been a serious incident on

his

spur for the past eight months.

He then tells

me a story about an occasion when he was released from prison some years ago

for a previous offence. He decided to call into his bank and cash a

cheque

. He climbed the steps, stood outside the bank and

waited for someone to open the door for him. He looks up from the end of the

bed at the closed cell door. ‘You see, it doesn’t have a handle on our side, so

you always have to wait for someone to open it.

After so long

in prison, I’d simply forgotten how to open a door.’

Fletch goes on

to tell me that being a Listener gives him a reason for getting up each day.

But like all of us, he has his own problems. He’s thirty-seven, and will be my

age, sixty-one, when he is eventually released.

‘The truth is

that I’ll never see the outside world again.’ He pauses. ‘I’ll die in prison.’

He pauses

again. ‘I just haven’t decided when.’

Fletch has

unwittingly made me his Listener.

6.27 am

Sundays are not

a good day in prison because you spend so much time locked up in your cell.

When you ask why, the officers simply say, ‘It’s because we’re short-staffed.’

I can at least

use six of those hours writing.

Many of the

lifers have long-term projects, some of which I have already mentioned.

One is writing

a book, another taking a degree, a third is a dedicated Listener. In fact,

although I may have to spend most of today locked up in my cell, Fletch, Billy,

Tony, Paul, Andy and Del Boy all have responsible jobs which allow them to roam

around the block virtually unrestricted. This makes sense, because if a

prisoner has a long sentence, they may feel they have nothing to lose by

causing trouble, but once you’ve given

them

privileges

– and not being locked up all day is unquestionably a privilege – they’re

unlikely to want to give up that freedom easily.

I shave using a

Bic

razor supplied by HMP.

They give you a

new razor every day, and it is a punishable offence to be found with two of

them in your cell, so every evening, just before lock-up, you trade in your old

one for a new one.

As soon as the

cell door is opened, I make a dash for the shower, but four young West Indians

get there before me. One of them, Dennis (GBH), has the largest bag of

toiletries I have ever seen. It’s filled with several types of deodorant and

aftershave lotions.

He is a tall,

well-built, good-looking guy who rarely misses a gym session. When I tease him

about the contents of his bag, Dennis simply replies, ‘You’ve got to be locked

up for a long time, Jeff, before you can build up such a collection on

twelve-fifty a week.’

Another of them

eventually emerges from his shower stall and comments about my not having

flipflops

on my feet. ‘Quickest way to get

verrucas

,’ he warns me. ‘Make sure Mary sends you in a pair

as quickly as possible.’

Having

repeatedly to push the button with the palm of one hand while you soap yourself

with the other is a new skill I have nearly mastered. However, when it comes to

washing your hair, you suddenly need three hands. I wish I were an octopus.

When I’m

finally dry, my three small thin green prison towels are all soaking – I should

only have one, but thanks to Del Boy…I return to my cell, and because I’m so

clean, I’m made painfully aware of the prison smell. If you’ve ever travelled

on a train for twenty hours and then slept in a station waiting room for the

next eight, you’re halfway there. Once I’ve put back on yesterday’s clothes, I

pour myself another bowl of cornflakes. I think I can make the packet (£1.47)

last for seven helpings before I’ll need to order another one. I hear my name

being bellowed out by an officer on the ground floor, but decide to finish my

cornflakes before reporting to him – first signs of rebellion?

When I do

report,

Mr

Bentley tells me that there’s a parcel for

me in reception. This time no one escorts me on the journey, or bothers to

search me when I arrive. The parcel turns out to be a plastic bag full of

clothes sent in by Mary: two shirts, five T-shirts, seven pairs of pants, seven

pairs of socks, two pairs of gym shorts, a tracksuit, and two sweaters.

The precise allocation that prison regulations permit.

Once

back in my cell I discard my two-day-old pants and socks to put on a fresh set

of clothes, and now not only feel clean, but almost human.

I spend a

considerable time arranging the rest of my clothes in the little cupboard above

my bed and as it has no shelves this becomes something of a

challenge.*

Once

I’ve completed the exercise, I sit on the end of the bed and wait to be called

for church.

My name is

among several others bellowed out by the officer at the front desk on the

ground floor, followed by the single word ‘church’. All those wishing to attend

the service report to the middle landing and wait by the barred gate near the

bubble. Waiting in prison for your next activity is not unlike hanging around

for the next bus. It might come along in a few moments, or you may have to wait

for half an hour.

Usually the latter.

While I’m

standing there, Fletch joins me on the second-floor landing to warn me that

there’s an article in the

News of the

World

suggesting that I’m ‘lording it’ over the other prisoners. Apparently

I roam around in the unrestricted areas in a white shirt, watching TV, while

all the other prisoners are locked up. He says that although everyone on the

spur knows it’s a joke, the rest of the block (three other spurs) do not.

Fletch advises me to avoid the exercise yard today, as someone might want ‘to

make something of it’.

The more

attentive readers will recall that my white shirt was taken away from me last

week because I could be mistaken for an officer; my feeble attempt to watch

cricket on TV ended in having to follow the progress of the King George and

Queen Elizabeth Stakes; and by now all of you know how many hours I’ve been

locked in my cell. How the

News of the

World

can get every fact wrong surprises even me.

The heavy,

barred gate on the middle floor is eventually opened, and I join prisoners from

the other three spurs who wish to attend the morning service. Although everyone

is searched, they now hardly bother with me.

The process has

become not unlike going through a customs check at Heathrow. There are two

searchers on duty this morning, one male and one female officer. I notice the

queue to be searched by the woman is longer than the one for the man. One of

the lifers whispers, ‘They can’t add anything to your sentence for what you’re

thinking.’

When I enter

the chapel I return to my place in the second row. This time the congregation

is almost 80 per cent black, despite the population of the prison being around

fifty-

fifty.

The service is conducted by a white officer

from the Salvation Army, and his small

band of singers are

also all white.

When I next see

Mr

Powe

, I must remember to

tell him how many churches, not so far away from

Belmarsh

,

have magnificent black choirs and amazing preachers who encourage you to cry

Alleluia. Something else I learnt when I was candidate for Mayor.