Heinrich Himmler : A Life (27 page)

Read Heinrich Himmler : A Life Online

Authors: Peter Longerich

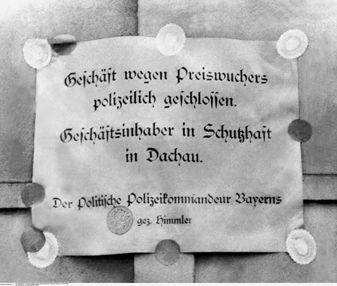

Ill. 8.

Himmler’s election to the Reichstag in September 1930 gave him financial security and immunity from prosecution. However, as a parliamentarian he was almost invisible. After giving up the Reich Propaganda department to Goebbels, Himmler concentrated on his leadership of the SS. Re-elected in July 1932, he along with the other Nazi deputies, swore an oath of personal loyalty to Hitler on 29 August in the Hotel Kaiserhof in Berlin.

From this point onwards the NSDAP came under increasing pressure. For years its supporters had been asked to make great sacrifices and been promised power in return, but now it appeared that, despite enormous electoral successes, the prospect of their taking over the government had receded into the far distance. The party leadership’s ‘tactic of legality’ appeared to have failed. When, in the middle of September, the Reichstag was dissolved and the party once again found itself facing the rigours of an election, its supporters became disappointed and apathetic. This was particularly true of the SA, but also affected the otherwise so reliable and disciplined SS, which in any case during the second half of the year had seen, by comparison with the rapid growth of the preceding months, only a modest increase in membership.

84

In September 1932 a number of internal reports on the mood in the SS reflect the mixed reactions within the organization. Thus Abschnitt IV (Brunswick) reported to headquarters that the ‘dissolution of the Reichstag and the resultant delay in the seizure of power initially caused the SS to be somewhat depressed’. But ‘belief in our final victory is unbroken [. . .] the troops are filled with a revolutionary spirit faithful to the National Socialist programme’,

85

a sentence which implies a pointed criticism of the ‘legal’ tactics of the party leadership, which were precisely not ‘revolutionary’.

The leader of SS-Gruppe East reported: ‘the mood of the SS in my Group area is good and has by no means given way to depression.’ However, the reporter then immediately qualified this statement by commenting: ‘It is only economic worries that make it more difficult for individuals to perform the duties they have taken on; it is only their financial concerns that make them vulnerable to depression.’

86

According to Gruppe South, the mood within the south German SS was ‘normal’. However, ‘our movement’s failure to take power [. . .] has produced a certain amount of depression and insecurity’.

87

Gruppe South-East (Silesia) reported that in general the mood was ‘good’; however, in some formations ‘there is discontent because the political situation is uncertain’.

88

Gruppe West reported: ‘the mood among the SS in Group West is very good, the SS’s fighting spirit is revolutionary, belief in victory and in the Führer is unshakeable’,

89

and, similarly, Abschnitt VII (Danzig) noted that ‘the mood’ was ‘calm and confident’.

90

The discontent in the SS hinted at here manifested itself among other things in increased tension with the SA, whose situation—they felt themselves cheated of their reward after years of ‘commitment’ to the movement—was almost desperate.

91

In the middle of December 1932 Röhm noted, in a confidential circular to the highest-ranking SA leaders and the Reichsführer-SS, that there had been an increase, ‘recently to an alarming extent’, in the number of ‘complaints about a deterioration in the relationship between the SA and SS’. He, therefore, requested his Inspector-General, Curt von Ulrich, to call a meeting of the highest-ranking SA leaders with a delegation of SS led by Himmler. The date was fixed for 10 January 1933.

92

However, by then the general political situation had long since changed. In the election of 6 November the Nazi Party suffered losses for the first time; it could secure only 33.1 per cent of the vote. Right-wing conservatives saw this result as a caesura: the NSDAP appeared to have passed the high-point of its success; now it ought to be possible to keep it under control within a coalition government.

At the beginning of December 1932 General von Schleicher succeeded in asserting his authority in a confrontation with von Papen. He made it clear to the cabinet that the Reichswehr would not be in a position to control the opposition forces of both Left and Right simultaneously. Thus, another way out of the crisis had to be found. When Hindenburg appointed him as von Papen’s successor in a cabinet that was otherwise hardly altered, von Schleicher was convinced that he could come up with another solution. Claiming the need to give priority to a work-creation programme, the new Chancellor endeavoured to form a ‘cross-party front’ made up of trades unions, professional organizations, Reichswehr, and Nazis, calculating that he could split off the ‘left’ wing of the NSDAP around Gregor Strasser from the rest of the party.

Strasser did indeed enter discussions with von Schleicher on the matter, but in the process isolated himself from the rest of the Nazi leadership, finally resigning from all his party offices on 8 December. Although Strasser had thereby become

persona non grata

in the NSDAP, Himmler still maintained contact with him. Even as late as April 1933 he employed Strasser, who was now working as an estate agent, to sell his property in Waldtrudering.

93

In the meantime von Papen, who was still highly regarded by Hindenburg, was working behind the scenes to construct a new government

involving the Nazis. The notorious first meeting between him and Hitler took place on 4 January 1933 at the Cologne home of the banker Kurt Freiherr von Schroeder. Himmler was actively involved, and indeed played a significant role, in the ongoing negotiations. A few days later, on 10 January, Himmler, accompanied by Hitler’s economic adviser Wilhelm Keppler, visited the Berlin businessman Joachim von Ribbentrop and, in Hitler’s name, asked whether he could arrange another meeting. On 18 January the two met again in Ribbentrop’s villa, where Hitler, Röhm, and Himmler lunched with von Papen. According to Ribbentrop, Hitler used this opportunity once more to request that he be given the Chancellorship. Von Papen declined the request on the grounds that Hindenburg would not accept it. In fact, he said that he himself wanted to become Chancellor, with Hitler’s support. But Hitler was not interested.

94

A few days later—in the meantime, Franz Seldte, the leader of the veterans’ organization the Stahlhelm, had declared his support for Hitler—von Papen changed his mind and declared himself willing to let Hitler become Chancellor. It was largely under his influence that Hindenburg was also persuaded to change his mind. Hindenburg now informed von Schleicher that he was not prepared to protect him from the Reichstag majority by granting him another dissolution of parliament. This obliged von Schleicher to resign and paved the way for a Hitler–Papen government.

II

Inside The Third Reich

The Takeover of the Political Police

On 30 January 1933 Hitler became Chancellor of a coalition government. Six months later the Nazis had taken control of the whole of the state apparatus, emasculated the Constitution, and become the dominant political force in almost every sphere of life. In brief, this process occurred in the following stages: the emergency decree of 28 February 1933 in response to the Reichstag fire, which suspended the most important civil rights enshrined in the Constitution; the victory of the Nazi-led coalition in the Reichstag election of 5 March; the Enabling Law of 24 March, which neutralized parliament and transferred legislative power to the government; the ‘coordination’ of the federal states; the elimination of the trades unions as well as of all political parties apart from the NSDAP; finally, the establishment of effective control over all interest groups, social organizations, and clubs right down to local level. By July 1933 the Nazis were in total command of the situation.

This takeover of power in stages was carried out by a clever combination of measures ‘from above’ and quasi-revolutionary ‘actions’ by the party’s rank and file. But terror played a central role.

1

Its effects were devastating. Nevertheless, during this phase it was by no means organized in a uniform manner or carefully coordinated. It was only during the course of the so-called ‘seizure of power’ that the Nazis succeeded in constructing a terror apparatus, and it would take quite a time before they had created a uniform system covering the Reich as a whole. Himmler became the key figure in this process and, in the end, was able to establish his authority in the face of all his rivals and opponents.

Essentially, the Nazis used the following political mechanisms to combat and terrorize their political opponents, and it was only gradually that they integrated them into a coordinated system: the takeover of the political police, its detachment from the regular police organization, and its utilization in the interests of the new regime; the appointment of SA and SS men as auxiliary police; the use of so-called ‘protective custody’, in other words, the indefinite internment of persons without due process,

2

as well as the establishment of numerous detention camps, in which the actual or alleged opponents of the new regime were subjected to unrestrained and arbitrary treatment. The whole situation was complicated by the fact that a power struggle developed within the various German states between the SA, SS, and the party’s political organization over who was to control the various instruments of terror, a struggle that produced different results in each state.

Hermann Göring, the second-most powerful man in the Nazi Party, was appointed acting Minister of the Interior in Prussia, the largest German state. He used his position to take control of the police and, by removing the political police from the general police administration, he was able to create a ‘Secret State Police’ (

Geheime Staatspolizei

= Gestapo) for combating political opponents. On 22 February he began recruiting ‘auxiliary police’ from the ranks of the SA and SS. However, both organizations began at once to exploit the situation by assuming a quasi-police role independently of the police authorities and detaining tens of thousands of alleged or actual opponents. They held them in makeshift camps, which they operated either autonomously or acting for the state authorities, who had effectively transferred to the SA and SS responsibility for guarding these prisoners.

3

Bavaria, the second-largest state, was the last to fall victim to the Nazi seizure of power. On 9 March Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick appointed the retired Lieutenant-General Franz Ritter von Epp, who was one of the most prominent Nazis in the state, to be Reich Governor in Bavaria under the pretext that Heinrich Held’s conservative government was incapable of maintaining order. The ‘proof’ for this assertion was provided by SA and SS units, whose rowdy demonstrations in Munich guaranteed the requisite disorder.

4

On the same evening as his appointment von Epp assigned to the Nazi Gauleiter of Upper Bavaria, Adolf Wagner,

the post of acting Bavarian Interior Minister, and to Heinrich Himmler the post of acting Munich police chief. Department VI of police headquarters, which controlled the political police, and which during the Weimar Republic had been responsible for combating political extremism throughout Bavaria, was taken over by Heydrich, who immediately began to build it up as an effective base.

5

Ill. 9.

[The notice reads]:

Business closed by the police on account of profiteering.

Proprietor is in protective custody in Dachau

The Bavarian Political Police Commander

Signed: Himmler

With the SS camp at Dachau, Himmler, as chief of the political police in Bavaria, had created a model for the future system of Nazi concentration camps. Right from the start Himmler understood how to exploit the terror associated with Dachau with carefully targeted publicity. As early as spring 1933 there was no need to explain what was implied by a reference to Dachau.