Heinrich Himmler : A Life (135 page)

Read Heinrich Himmler : A Life Online

Authors: Peter Longerich

93

. TB, 2 July 1922.

94

. TB, 4 June 1922.

95

. TB, 5 July 1922. Himmler had allowed himself to be recruited for an anti-Republican initiative, which, however, was unsuccessful in getting its proposal put to a referendum. There is a copy of the statutes of the League in Staatsarchiv Freiburg, A 40/1, no. 174.

96

. TB, 5 July 1922.

97

. TB, 19 June 1921.

98

. TB, 9 June 1922; see Smith,

Himmler

, 163.

99

. TB, 2 July 1922.

100

. TB, 13 November 1921.

101

. Gebhard completed his diploma in Mechanical Engineering in July 1923, Ernst completed his diploma in Electrical Engineering in 1928; see Himmler,

Brüder Himmler

, 95 and 131.

102

. TB, 9 June 1922. He was already complaining about the high lecture fees and the high prices of textbooks on 4 November 1921.

103

.

Zahlen zur Geldentwertung in Deutschland 1914 bis 1923

, bearb. im Statistischen Reichsamt (Berlin, 1925), 5. On the effects of hyperinflation on Munich see Martin H. Geyer,

Verkehrte Welt. Revolution, Inflation und Moderne, München 1914–1924

(Göttingen, 1998), 319 ff.

104

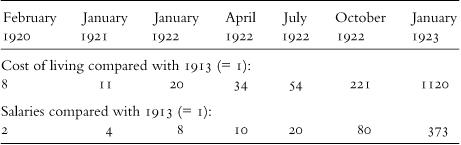

. This is shown by a comparison of the cost-of-living indices and the salaries of senior Reich officials (the incomes of senior Bavarian officials were similar):

105

. See Smith,

Himmler

, 162.

106

. BAK, NL 1126/1, copy of the diploma.

107

. BAK, NL 1126/17, letter from Prof. Hudezeck, 15 August 1922; see Smith,

Himmler

, 222.

108

. BAK, NL 1126/1, copy of the reference from Stickstoff-Land-GmbH Schleissheim, 30 August 1923.

109

. On the 1923 crisis and the prehistory of the Hitler putsch see Gerald D. Feldman,

The Great Disorder: Politics, Economics, and Society in the German Inflation

,

1914–1924

(New York and Oxford, 1993), 631 ff.; Fenske,

Konservativismus

, 188 ff.; Heinrich August Winkler,

Weimar 1918–1933. Die Geschichte der ersten deutschen Demokratie

(Munich, 1993), 186 ff.

110

. On the course of the Hitler putsch see Hanns Hubert Hofmann,

Der Hitlerputsch. Krisenjahre deutscher Geschichte, 1920–1924

(Munich, 1961); Harold J. Gordon,

Hitlerputsch 1923. Machtkampf in Bayern 1923–1924

(Frankfurt a. M., 1971); John Dornberg,

Hitlers Marsch zur Feldherrnhalle. München, 8. und 9. November 1923

(Munich, 1983).

111

. StA München, Pol. Dir. München 6712, interrogations of Seydel und Lembert.

1

. In his diary entry for 14 February 1924 Himmler expressed his frustration and disappointment at his unsuccessful attempts to find work. It is clear from a letter from an acquaintance, Maria Rauschmayer, dated 13 June 1924 (BAK, NL 1126/17), that, prompted by Himmler’s mother, she had been trying to ask around about a job in agriculture for him.

2

. TB, 11, 13, 14, and 15 February 1924; evidently he was awaiting mail which was supposed to be left in the Schützen or ‘Fasching’ pharmacy. (According to Karl Wolff, his fellow fraternity member, Fasching, worked in the Schützen pharmacy: StA München, 34865/9, interrogation of 16 February 1962.) On 11 February Himmler referred to arrests of putschists in his diary; on 15 February he noted more details about the role of one of those arrested.

3

. TB, 15 February 1924.

4

. In 1924 Gebhard Himmler was registered as living at Marsplatz 8 (II Floor), see

Adressbuch für München 1924

.

5

. BAB, BDC, Research Ordner 199, NSDAP headquarters to Himmler, 12 August 1925, with enclosure: National Socialist local branches in Lower Bavaria.

6

. On his work on the article for the

Langquaider Zeitung

see TB 11, 12, and 17 February 1924; on its publication in the

Rottenburger Anzeiger

see TB, 23 February 1924.

7

. TB, 24 February 1924.

8

. TB, 25 February 1924.

9

. TB, 24 February 1924.

10

. Lothar Gruchmann and Reinhard Weber, with the assistance of Otto Gritschneder (eds),

Der Hitler-Prozess 1924. Wortlaut der Hauptverhandlung vor dem

Volksgericht München

I, 4 vols. (Munich, 1997–9), here vol. 2 (Munich, 1998), 642. This shows that the defence offered to call Himmler as a witness to the aggressive behaviour of a Reichswehr officer who, on 9 November, was placed with his troops opposite to the Reichskriegsflagge in front of the War Ministry.

11

. BAK, NL 1126/7, letters from Hajim (?) Mazhar, 24 November 1923, 16 April 1924, and 15 March 1925; reference in TB, 14 February 1924.

12

. TB, 11, 14, and 15 February 1924.

13

. TB, 12 February 1924.

14

. BAK, NL 1126/17, Robert Kistler to Himmler, 17 June 1924.

15

. Ibid. letter of 5 November 1924.

16

. TB, 7 November 1921 and 31 May 1922. On the ‘Paula affair’ see also Smith,

Himmler

, 198ff.

17

. TB, 12 November 1921 He had read the book in December 1920 and commented on it as follows: ‘A book that presents the ideal of a woman as pure feeling and shows us woman simply as a goddess, as she often appears as a goddess to a true man. It is a hymn of praise to woman and to a feeling that is beautiful and idealized.—If only it could come true in the world we live in and if only the goddess woman did not have so many flaws’ (Leseliste no. 72).

18

. This is suggested by Paula Stölze’s comment in her letter to Gebhard of 4 March 1924 that at the time she had considered Heinrich’s letter to be ‘not quite right’ (BAK, NL 1126/13).

19

. Ibid. Himmler to Paula Stölzle, italics in the original. It was a draft of 18 April 1923, which was sent in that or similar form as is clear from Paula’s response, in particular her unwillingness to be ‘lectured to’ by Heinrich.

20

. Ibid. 1 July 1923.

21

. Ibid.

22

. Ibid. 11 February 1924.

23

. The break-up is clear from various letters in BAK, NL 1126/19: Gebhard Himmler’s letter to the parents of his fiancée, 27 February 1924, as well as to Paula, 28 February 1924; Paula’s reply as well as that of her father, Max Stölzle, both dated 4 March 1924. Gebhard then replied on 10 March 1924.

24

. BAK, NL 1126/13, 4 March 1924.

25

. Ibid. letter from the private detective, Max Blüml, dated 14 March 1924, to Himmler, who had given him the job on 9 March 1924.

26

. Ibid. letter to Rössner, 12 March 1924, reply of 18 March 1924.

27

. TB, 18–22 February 1924. A reference to a further stay with these friends is contained in the Leseliste no. 202 (28 February–5 March 1924).

28

. BAK, NL 1126/17, 23 May 1924.

29

. Maria Rauschmayer, born on 29 May 1901 in Dillingen, began her study of German at Munich University in winter semester 1919. She submitted a dissertation on the Reformation in 1924, but did not complete the degree (information from the Munich University archive).

30

. TB, 2 June 1922.

31

. BAK, NL 1126/17, Maria Rauschmayer to Himmler, 13 June 1924, received on 17 June 1924, see also the letter from Maria Rauschmayer of 18 November 1923.

32

. Ibid. 2 August 1924.

33

. Leseliste no. 175, Friedrich Zur Bonsen,

Das zweite Gesicht

(Cologne, 1916), read 29 November–4 December 1923: ‘Intellectually serious and lucid study.’

34

. Geyer,

Verkehrte Welt

, 309 ff., points out that during the hyperinflation medical and religious cranks were popular and that ‘alternative’ doctrines like Theosophy, Occultism, Spiritualism, and Anthroposophy had a big impact. See also Ulrich Linse,

Barfüßige Propheten. Erlöser der Zwanziger Jahre

(Berlin, 1983).

35

. Leseliste no. 246, Heinrich Jürgens,

Pendelpraxis und Pendelmagie

(Pfullingen, 1925), read 25 August 1925.

36

. BAK, NL 1126/17; however, he was turned down because the astrologer did not have enough facts (letter from Studienrat C. Heilmaier to Himmler, 19 September 1925).

37

. Leseliste no. 148, Max Eyth,

Der Kampf um die Cheopspyramide

, 8th edn (Heidelberg, 1921), read 19–23 February 1923.

38

. Ibid. no. 148, Karl Du Prel,

Der Spiritismus

, new edn (Leipzig, 1922), read January and February 1923: ‘A serious little work with a philosophical basis which has really made me believe in Spiritualism and has really introduced me to it for the first time.’

39

. Ibid. no. 86, Matthias Fidler,

Die Toten leben! Wirkliche Tatsachen über das persönliche Fortleben nach dem Tode

(Leipzig, 1909), read 30 April and 2 May 1921.

40

. Ibid. no. 111, read December 1923.

41

. Ibid. no. 191, read 9 February 1924.

42

. Ibid. no. 167, Christian Heinrich Gilardone,

Eppes Kittisch!! Noch ä Beitraagk zu Israels Verkehr und Geist

(Speyer, 1843), read 8–14 October 1923.

43

. Ibid. no. 171, Theodor Fritsch,

Handbuch der Judenfrage

, 29th edn (Leipzig, 1923), read 25 September–21 November 1923.

44

. Ibid. no. 176, Theodor Fritsch,

Der falsche Gott. Beweismaterial gegen Jahwe

(Leipzig, 1920), read 1–5 December 1924.

45

. Ibid. no. 200, Erich Kühn,

Rasse? Ein Roman

(Munich, 1921), read 27 February 1924: ‘Naturally deals with the Aryan and Jewish racial problem. The seduction and incarceration of this German girl is handled particularly well’. Ibid. no. 201, Edward Stilgebauer,

Die Lügner des Lebens. Das Liebesnest

(Berlin, 1908), read 20–9 February 1924: ‘Jewish blood and Jewish sensuality depicted fairly well. The novel deals with inferior people with only a few exceptions.’

46

. Ibid. no. 216,

Eine unbewusste Blutschande. Der Untergang Deutschlands. Naturgesetze über die Rassenlehre

(Grossenhain i. S., 1921), read 17 September 1924: ‘A marvellous book. It’s a pioneering work. Particularly the last part on how it’s possible to improve the race again. It’s on a terrifically high moral level.’