Heaven: A Prison Diary (37 page)

Read Heaven: A Prison Diary Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous

Devon is the

spur’s senior cleaner. He tells me with considerable pride that he is fortyone,

has five children by three different women and already has five grandchildren.

I tell him my needs. He smiles; the smile of a man who can deliver.

Within the

hour, I have a second pillow, a blanket, two bottles of water, a KitKat and a

copy of yesterday’s Times. By the way, like Del Boy, Devon is West Indian. As

Devon is on remand, he’s allowed far longer out of his cell than a convicted

prisoner. He’s been charged with attacking a rival drug dealer with a machete

(GBH). He cut off the man’s right arm, so he’s not all that optimistic about

the outcome of his forthcoming trial.

‘After all,’ he

says, flashing a smile, ‘they’ve still got his arm, haven’t

they.

’

He pauses. ‘I only wish it had been his head.’ I return to my cell, feeling

sick.

I find it

difficult to adjust to being banged up again for twenty-two hours a day, but

imagine my surprise when, during association – that forty-five-minute break

when you are allowed out of your cell I bump into Clive. Do you remember Clive?

He used to come to the hospital in the evening at North Sea Camp and play

backgammon with me, and he nearly always won. Well, he’s back on remand, this

time charged with money laundering. As we walk around the yard, he tells me

what’s been happening in his life since we last met.

It seems that

after being released from NSC, Clive formed a company that sold mobile phones

to the Arabs, who paid for them with cash. He then distributed the cash to

different banks right around the globe, while keeping 10 per cent for himself.

‘Why’s that

illegal?’ I ask.

‘There never

were any phones in the first place,’ he admits.

Clive seems

confident that they won’t be able to prove money laundering, but may get him

for failure to pay VAT.

38

During

association, I phone Mary. While she’s briefing me on Narey’s attempts on radio

and television to defend his decision to send me to Lincoln, another fight

breaks out.

I watch as two

more prisoners are dragged away. Mary goes on to tell me that Narey is

backtracking as fast as he can, and the Home Office is nowhere to be seen. The

commentators seem convinced that I will be transferred back to a D-cat fairly

quickly. It can’t be too soon, I tell her, this place is full of violent,

drug-addicted thugs. I can only admire the way the officers keep the lid on

such

a boiling cauldron.39

While I roam

around association with Jason, he points at three Lithuanians who are standing

alone in the far corner.

‘They’re on

remand awaiting trial for murder,’ he tells me. ‘Even the officers are fearful

of them.’ Devon joins us, and adds that they are hit men for the Russian mafia

and were sent to England to carry out an execution. They have been charged with

killing three of their countrymen, chopping them up into little pieces, putting

them through a mincer and then feeding them to dogs.

11.00 am

The cell door

is opened and an officer escorts me to the chapel: anything to get out of my cell.

After all, the chapel is the largest room in the prison. The service is Holy

Communion with the added pleasure of singing by choristers from Lincoln

Cathedral. They number seventeen, the congregation thirteen.

I sit next to a

man who has been on

A

block for the past ten weeks.

He’s fifty-three years old, serving a two-year sentence. It’s his first

offence, and he has no history of drugs or violence.

The Home

Secretary can have no idea of the damage he’s causing to such people by forcing

them to mix in vile conditions with murderers, thugs and drug addicts. Such men

should be sent to a D-cat the day they are sentenced.

40

I go to the

library and select three books, the maximum allowed. I spend the next twenty

hours in my cell, reading.

I end the day

with Alfred Hitchcock’s

Stories

To Be Read With The

Doors Locked

.

Somewhat

ironic.

,

6.00 am

Over the past

few days I have been writing furiously, but I have just had my work confiscated

by the deputy governor – so much for freedom of speech. He made it clear that

his orders to prevent me from sending out any written material came from the

Home Office direct. I rewrite my day, and have this copy smuggled out – not too

difficult with nearly a hundred prisoners on remand who leave the prison to

attend court every day.

After

breakfast, I’m confined to my cell and the company of Jason for the next eight

hours.

Mr Marsh, a

senior officer, who has a rare gift for keeping things under control, opens the

cell door and tells me I have a meeting with the area manager.

41

I am

escorted to a private room, and introduced to Mr Spurr and Ms Stamp. Mr Spurr

explains that he has been given the responsibility of investigating my case. As

I have received some 600 letters during the past four days (every one of them

retained), every one of them expressing outrage at the director-general’s

judgment, this doesn’t come as a great surprise.

Mr Spurr’s

intelligent questions lead me to believe that he is genuinely interested in

putting right an injustice. I tell him and Ms Stamp exactly what happened.

On Friday 27

September, the Prison Service announced that ‘further serious allegations’ had

been made against me. It turned out these related to a lunch I had attended on

Wednesday 25 September in Zucchini’s Restaurant, Lincoln (which is near the

Theatre Royal) with Mr Paul Hocking, then a Senior Security Officer at North

Sea Camp, and PC Karen Brooks of the Lincolnshire Constabulary.

I explained to

Mr Spurr that the sole purpose of the lunch as far as I was concerned was so

that I could describe what I had seen of the drug culture permeating British

prisons to PC Brooks, who had by then returned to work with the Lincolnshire

Police Drug Squad. After all, I’d had several meetings with Hocking and or

Brooks in the past on the subject of drugs. I did not know that prison officers

are not supposed to eat meals with prisoners, nor is there any reason I should

have known this. Moreover, when a senior officer asks a prisoner to attend a

meeting, even in a social context, a wise prisoner does not query the officer’s

right to do so.

As for SO

Hocking, I have been distressed to learn that he was summarily forced to resign

from the Prison Service on 27 September under the threat of losing his pension

if he did not do

so42.

PC Karen Brooks was more fortunate in her

employers. Her role was investigated comprehensively by Chief Inspector Gossage

and Sergeant Kent of the Lincolnshire Police, and she remains with the force.

Chief Inspector Gossage and Sergeant Kent interviewed me during their later

investigation of the same lunch, and made it very clear that they thought the

Prison Service had acted hastily and disproportionately in transferring me to

HMP Lincoln.

As Mr Spurr

leaves, he assures me that he will complete his report as quickly as possible,

although he still has several other people to interview. He repeats that he is

interested in seeing justice being done for any prisoner who has been unfairly

treated.

It was some

time later that the

Daily Mail

reported

that the Home Secretary had bullied Mr Narey into the decision to have me moved

to HMP Lincoln.

The

sequence of events, so far as I am able to establish them, are

as follows. The

Sun

newspaper

telephoned Martin Narey’s office on the evening of Wednesday 25 September and

the following day published a highly coloured account of the Gillian Shephard

lunch.

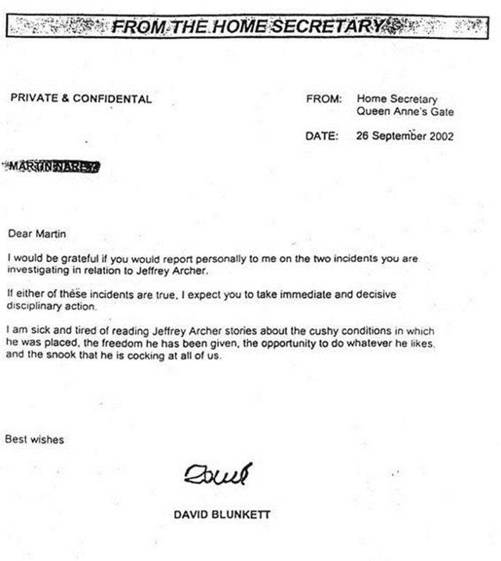

This provoked

the Home Secretary to send an extraordinary fax (see overleaf) to Martin Narey

demanding that the latter take ‘immediate and decisive disciplinary action’

against me. Narey, who had previously stood up against the press’s attempts to

portray my treatment as privileged, buckled and instructed Mr Beaumont to

transfer me forthwith to Lincoln. Narey also went on a number of TV and radio

programmes to criticize me in highly personal terms in what the

Independent on Sunday

described as ‘an

unprecedented attack on an individual prisoner’, especially in the light of

later pious assertions that the Prison Service is ‘unable to discuss individual

prisoners in detail with third parties’.

Mr Beaumont

found himself in even more difficulty: he had not asked me about the Zucchini

lunch, so he could hardly make that the basis of an order to transfer me. In

the event, the Notice of Transfer which he signed stated simply: ‘Following

serious allegations reported in the media and confirmed by yourself that on 15

September 2002, you attended a dinner party rather than spend the day on a

Community Visit in Cambridge with your wife, it is not appropriate for you to

remain at HMP North Sea Camp any longer.’

My licence did

not

restrict me to my home in

Grantchester while on release. But, an e-847/907 mail was circulated within the

Home Office which stated:

‘The prison

[HMP

North Sea Camp]

had granted JA home leave

but his licence conditions stipulated that he should not go anywhere else but

home. In light of this, he has breached his licence conditions, and will face

adjudication.’

At that time, the copy of my master passbook (a record

retained by the prison which records all a prisoner’s releases on temporary

licence) contained no such stipulation, nor did I ever face adjudication in

respect of any breach of such a stipulation.

Mr Spurr later

said in a letter he was ‘unable to locate’ my master passbook when he conducted

his investigation into my transfer, a fact which he acknowledged as

‘regrettable’. One has to wonder why and how this passbook disappeared.

However, Mr Narey told me to stop writing to him on the subject as the matter

was closed.

6.00 am

A frequent

complaint among prison officers and inmates – with which I have some sympathy –

is that paedophiles and sex offenders are treated more leniently, and live in

far more palatable surroundings, than the rest of us.

On arriving at

Lincoln you are immediately placed on

A

wing,

described quite rightly by the tabloids as a Victorian hellhole.

But if you are

a convicted sex offender, you go straight to E wing, a modern accommodation

block of smart, single cells, each with its own television. E wing also has

table tennis and pool tables and a bowling green.

During the past

few days, I have been subjected to segregation, transferred to Lincoln, placed

in A block with murderers, violent criminals and drug dealers, in a cell any

selfrespecting rat would desert, offered food I am unable to eat and I have to

share my cell with a man who thrashed someone to within an inch of their life.

All this for having lunch with the Rt Hon Gillian Shephard in the

company of my wife when on my way back to NSC from Grantchester.

Sex offenders

can survive in an open prison because the other inmates are on ‘trust’ and

don’t want to risk being sent back to a B... cat or have their sentences

extended.

However, these rules

do not apply in a closed prison. An officer recently reported to me the worst

case he had come across during his thirty years in the Prison Service. If you

are at all squeamish, turn to the next page, because I confess I found this

very difficult to write.

The prisoner

concerned was charged and convicted of having sex with his five-year-old

daughter. During the trial, it was revealed that not only did the defendant

rape her, but in order for penetration to take place he had to cut his

daughter’s vagina with a razor blade.

I know I

couldn’t have killed the man, but I suspect I would have turned a blind eye

while someone else did.

I have a visit

from a Portuguese prisoner called Juan. He warns me that some inmates were seen

in my cell during association while I was on the phone. It seems that they were

hoping to get their hands on some personal memento to sell to the press.

English is

Juan’s second language, and I have not come across a prisoner with a better

command of our native tongue; and I doubt if there is another inmate on

A

block who has a neater hand – myself included. He is,

incidentally, quietly spoken and well mannered. He wrote me a thank you letter

for giving him a glass of blackcurrant juice. I must try and find out why he is

in prison.

An officer (Mr

Brighten) unlocks my door and tells me that he needs a form filled in so that I

can work in the kitchen. To begin with, I assume it’s a joke, and then become

painfully aware that he’s serious. Surely the staff can’t have missed that I’ve

hardly eaten a thing since the day I arrived, and now they want to put me where

the food is prepared? I tell him politely, but firmly, that I have no desire to

work in the kitchen.