Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (26 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

Coney Island Hospital seemed the stuff of nightmares to us kids. We’d heard about people going there, but they never seemed to come out. We were sure it was the place where you went to die. Once my father and I arrived, its appearance more than lived up to my worst fears: dark, dank hallways, cheerless gray rooms filled wall to wall with beds inhabited by ghastly looking sick people.

The elevator took us to the top floor, where we exited onto a dark hallway. At the far end was a single large room, blindingly illuminated by numerous hanging lights. In the room were row upon row of iron lungs, lined up in neat columns. Protruding from the end of each one was a solitary head resting on a pillow. Above each head was a tilted mirror. By looking at this mirror, each patient could see what lay immediately behind him.

Looking in his mirror, Barry saw me. And looking in the same mirror, I saw Barry’s upside-down face—and watched him smile at me.

Only Barry’s head was visible. The rest of him lay hidden in the iron lung.

Barry and I had a good visit. I told him about all the happenings on the block since he had gotten sick. (I didn’t once mention the word

polio.

) Some of my stories made him laugh.

He told me I could ride his bike until he came home and could use it himself.

Soon a nurse came by and ushered us out, telling us, “This boy needs his rest.”

We said our goodbyes, and as I was leaving, he said, “You know, I have polio.”

On the way home in the subway car, my father signed to me his sadness. “Poor, poor boy.”

But then he signed something surprising. “Now I know why I never heard of a deaf person getting polio.” He paused, thinking. “God wouldn’t do that to a deaf person. How would a deaf person talk, if his hands were hidden in an iron lung? How would a deaf person sign his fears with hidden hands?” My father did not sign an additional thought all the way home.

That fall it rained almost every day. Barry’s bike sat on his porch, exactly where he had left it after his last ride, a mute reminder of my friend. It was never taken in when it rained, and by the beginning of winter it was covered in rust. With winter’s first snowfall, it disappeared completely under a layer of snow, which meant that now when I looked over at his silent white porch as I left my apartment building each morning, the image of Barry in his iron lung, unable to ride his bike, no longer leaped unbidden into my mind.

For my father, however, the thought of polio was much on his mind all that winter, as was his God, the god who would inflict polio on a young boy.

I had no interest in God as represented by the dilapidated wooden synagogue around the corner from us, with its smelly, impossibly foreign-looking men dressed in the same drab black clothing year round. This mysterious exclusive gathering was the world of my father’s father, not mine. My world was the

moment,

as represented by my Brooklyn block, not a history five thousand years old.

But I was never clear how my father felt about this subject. Our family did not observe the Sabbath. We did not keep any Jewish holidays, as many—though not all—of my Jewish friends did. Although my father had had a bar mitzvah—an experience, he told me, that was totally incomprehensible to him—he knew no prayers. He did not attend weekly services at our neighborhood synagogue, or even High Holy Day services. What would have been the point? He could not sing the hymns, nor read the words. God did not speak to him, and if He did, my father could not hear Him. There were no signs known to the deaf for the ancient Hebrew words, so how could he speak to God, in God’s language?

My father talked to me about everything, but not his God. One day, however, my father came home early from work. There was a snowstorm, and he had been given a half-day off with pay, as the paper supply had been exhausted, and fresh newsprint inventory was stuck on trucks stranded in snowdrifts north of the city. As usual, he had the day’s paper folded under his arm, but there was not much to it since there was no sports news (thanks to the snowstorm), no reports of murders the night before in Brooklyn (probably for the same reason), and very little in the way of war news (fortunately). Lacking any news to discuss with me, and being in an unaccountably thoughtful mood, my father began, that afternoon, a halting monologue about the role God had played in his life.

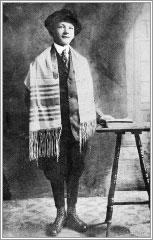

My father’s bar mitzvah, 1915

“My father was a deeply religious man from the old country,” he signed to me. “And in the old country his father was a cantor. I was told as a boy that my father had a sweet voice. I have some memory of this, but I can never pin it down in my mind. I remember him covering himself every morning with his shawl, and then wrapping his arm and forehead with his tefillin, which he kept in a burgundy velvet bag embroidered in heavy gold thread with Hebrew words.” My father’s sign for

Hebrew

was clear: his two hands descended downward from his chin repeatedly, opening and closing as if stroking a long imaginary beard. “Then my father would bend up and down repeatedly, and talk to someone; someone I couldn’t see, but who was in the room with us. I knew he was talking, because I saw his lips moving, moving, moving.

“But as observant a Jew as my father was, when I was a boy he never involved me in his daily rituals. And how could he? We never talked. We had no real language.

“So I never knew who God was. It was a mystery all my life. Still is. Like everything else for us deaf, life is a puzzle, and we have only ourselves to solve the thousands of pieces of the puzzle.” While he was telling me this, his fingers revolved around each other, as if they were manipulating pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, a giant ever-changing puzzle that only he could see. Then my father looked at me for the longest time. “Sometimes I

hate

God. He made me deaf, but not my sisters or my brother. Why was that? I was only a little boy. What did I do wrong? I never understood. And now look at your friend Barry. Such a sweet boy. He always smiles at me and tries to sign

hello

to me. Now he will never ride his bike again. Why would God do such a thing?

“And what kind of god would cause your brother, a sweet beautiful boy who never hurt anyone, to be an epileptic? Why did God strike him so? Does God see him when he falls down? Does God care when he bites his tongue and his blood flies everywhere?”

My father expected no answer from me. He sat there at the kitchen table, deeply troubled. I could read it on his face and in the slump of his shoulders. For the longest time my father continued to stare into space, lost in the maze of unanswerable questions, until I saw him slowly begin to refocus. He was looking at me with a strange expression on his face, and his hands began to move.

“But just when I curse God, I think of Mother Sarah. I think of you and your brother. And I think this puzzle will never be answered.”

Memorabilia

The End of the Presidency

O

n April 12, 1945, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt died unexpectedly in Warm Springs, Georgia. He had looked increasingly old, weary, and sad as the war dragged on. But as he was the only president I had ever known, his death was shocking news to me. That night, as always, my father brought home the newspaper. After supper he signed the front-page headline: “FDR DEAD.” His sign was as bold and black as was the bold, black-printed headline. My father’s hands were sad and mournful. “He was a cripple. He had polio as a young man. Until then he was just like any other young man.” Then he stopped. “I was just like any other boy, until I got sick. Then I was crippled in my ears, just like the president was crippled in his legs. But look what FDR could do. He won the war.”

Then my father cried. I had never seen my father cry before. He did not make a newspaper hat from the front page that night.

18

A Boy Becomes a Man

O

n August 6, 1945, a lone American plane dropped a single bomb on the city of Hiroshima, signaling the end of World War II.

One month earlier, the day after I turned twelve, my father had dropped a bomb on me. He informed me that I would have my bar mitzvah when I was thirteen, a year later. That news was as shocking to me as the news of the atomic bomb. Bar mitzvah? Since when, I wondered, was my father interested in the traditions of the Jewish religion? Until the day he spoke to me about his sense of alienation from God, I’d never gotten the impression that religion occupied any space, positive or negative, in his thoughts.

Although born of Jewish parents, he had had no formal Jewish upbringing, unless you counted the mock bar mitzvah he had undergone. All he remembered of that event, he told me, was being unaccountably dressed in a suit and hat one Saturday upon turning thirteen, and accompanying his father to the local

shul,

the storefront house of worship. There he was pushed onto a wooden stage, where he stood with a prayer shawl draped around his shoulders and a man’s hat on his head. Then he watched carefully, but with a total lack of comprehension, while the gray-bearded rabbi faced him, his hair-shrouded lips moving, my father said, a mile a minute.