Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (18 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

I was intrigued even then by the wild diversity of language on display, the different styles reflecting a wide variety of personalities and geographic origins, as well as differences between the sexes. The men tended to sign more aggressively, more assertively than the women. The outgoing personalities signed expansively, while the shy tended to make smaller, more guarded signs. Some were so reserved that they made only the most tentative gestures in the air, constipated strings of small, stunted signs. Some signed with abandon, even boisterously, while others signed demurely. Some signed loudly, some softly. Some signed with comic exaggeration, while the signing of others was more controlled, more thoughtful. A couple who had moved to the Bronx from a small town in Georgia signed with an accent I didn’t recognize. My father told me they signed with a drawl, and it was true that their signs did seem to flow from their hands like syrup, thick and slow.

Strangely, there was one deaf lady who had suffered a stroke many years before who seemed to stutter when she signed. It was as though her signs stuck to her hands. Impatiently, she shook them off her fingers in an attempt to be understood.

One man’s signs seemed halting, primitive, even childish. My father caught me staring, with what must have been a puzzled look on my face, and explained.

“When he was a boy, he lived on a farm. He grew up deaf on that farm. He had a big hearing family, but his family had no sign. His family was poor. It was a hard life. His father needed the boy to help with the farm work. Finally the boy went to deaf school when he was fourteen years old. There he learned sign. But it was too late. He never learned good. He is still a little deaf boy in his own mind. Now all the time he talks like a child. Simple. He never gets better. Sad.”

My father’s signs tended to be quick, impatient, insistent—typical of the signs of the deaf who live in a big city.

Many years later I looked back on that panorama of word-pictures painted in the air above the sand of Coney Island and saw that it was as complex and as colorful in its own way as the ceiling above the Sistine Chapel.

“Where is Sally?” one set of hands asked. (Sally was the nickname by which my mother had been known ever since her teenage days at the Lexington School for the Deaf.) Those hands belonged to Ben from Coney Island. He had been one of my mother’s many boyfriends when she was a young girl.

“She’s home. My wife, Sarah, has a cold,” my father answered, carefully spelling out the name

Sarah

and emphasizing the word

wife.

My father hated Ben and had never gotten over my mother’s long-ago interest in him.

“Sure, he’s a good-looking guy,” I observed him say one day to Mort, a close friend he’d first met at Fanwood, the deaf school they’d both been sent to as children.

“Sure, he still has all his hair, but I bet it’s dyed. And he fools around on his wife, Mary,” he added, his hands whispering in small guarded signs so no one else could see what he was signing.

“Ah, Lou, let it go, will you?” Mort signed. “That was fifteen years ago. Who cares? You are a union man, and he’s a bum!”

“Easy for you to say,” my father answered him.

“My

wife,

Sarah, says hi,” he added to Ben, while his grim face belied the pleasant greeting.

Just then four more deaf couples arrived, lugging beach chairs and picnic baskets and beach umbrellas, their kids hanging on for dear life lest they be lost in the commotion.

The circle readjusted to accommodate the newcomers. Down went the beach chairs and up went the hands, fluttering wildly like the wings of a flock of geese taking flight at the sound of a shotgun blast. They had not seen one another since last weekend, and there was much news to tell.

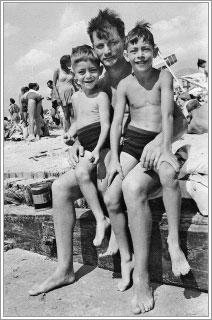

Irwin and I with our father at Coney Island

We kids sat on beach towels in the middle of the ever-expanding circle, like small animals in a human cage made up of our parents, beach chairs, and beach umbrellas, our protection against the possibility of getting lost. To be lost in Coney Island on a Sunday in August was a scary experience for any kid, but especially for a kid whose parents were deaf. When lost (an ever-present danger, since the beach was so crowded), the child would invariably be accosted by an adult sympathetic to the sight of a child crying his heart out, who would take him to the nearest lifeguard station. I say “him” because girls rarely wandered off and got lost in those days. There the lifeguard would ask the kid his name. Armed with that essential information, the lifeguard would dangle the kid over the railing of his elevated perch, while blowing his whistle in a series of ear-splitting screeches. In our case, of course, the whistle was useless, as the sound fell on what were literally deaf ears. We could only hope that our parents would eventually notice we were missing and maybe, just maybe, stop talking to their friends long enough to come looking for us.

By late afternoon, when the last of the arrivals had finally made it, having traveled by ferry and subway all the way from Staten Island, there were well over one hundred beach chairs in a perfect circle. A deaf man or woman occupied each chair. And each man or woman was signing frantically to another man or woman in the circle, sometimes to one clear across the circle, far away.

There were few secrets in the deaf community at Coney Island.

“What do the waves sound like?” my father asked me out of the blue. “I see them crashing onto the shore. They must make a sound.”

I was building a sand castle. The thick sand walls were water-dampened and-hardened. Three tall mud-dripped turrets stood atop a fantastic-looking structure adorned with battlements and scooped window openings. A bridge crossed a moat. And I was now sculpting small sand soldiers to guard the whole affair. I had no time to tell my father what things sounded like. I pretended I didn’t see his hands.

He shook me, not too gently. “What do the waves sound like?” he repeated.

It was no use.

Here we go again,

I thought. “Loud,” I answered him without thinking. “Loud they must be,” he signed patiently, “but many things are loud. I feel loudness through the soles of my feet. But every loud thing must be loud in its own way.” He had me there.

“Well,” I sighed while signing, my shoulders lifting to signal that I was thinking, my features arranging themselves in an expression suggesting that I was not sure of my answer but would do the best I could.

“They sound

wet

when they crash down on the sand.”

As soon as I said that, I knew my father would ask what

wet

sounded like. No sooner had my fingers touched my lips, and then opened and closed against my thumbs as they made the sign for

wet,

than my father demanded, “What kind of wet? Wet like a wild river? Wet like soft rain? Wet like sad tears?”

I was stumped. “Wet like waves!” was all I could come up with at first. I finally signed, “Waves sound like a billion wet drops breaking apart when they smack down on the hard sand, all the tiny sounds joining to make one great sound. A

wet

falling ocean sound,” I added desperately.

My father took me into his arms and held me. Letting go, he got down on his knees in the sand and signed, “That’s better. I understand now.”

Just then Mort shook my father’s shoulders. “Lou! Lou! Look! Here comes Sally.”

Sure enough, my mother had entered the deaf circle, holding my brother’s hand. She was in her blue two-piece knitted-wool bathing suit. She wore a white rubber bathing cap with tiny yellow rubber flowers attached, covering her close-cropped black hair. She always wore her hair short in the summer. She looked beautiful. Before my mother even set down her beach chair, Ben was in her face, signing wildly like a windmill in a windstorm.

I could swear I saw my father mutter to himself in sign, “I’ll murder that guy.”

My mother signed a greeting to Ben, then held his arms to his sides, silencing him, and turned to my father with a smile from ear to ear.

If my father had been an Eskimo Pie, he would have melted in the warmth of that smile.

12

The Triangle and the Chihuahua

L

ong ago, children in Brooklyn public schools were exposed to more than academic and “practical” subjects. In addition to art appreciation, there was music appreciation. But this form of appreciation found me as wanting as art appreciation did, since I was virtually tone deaf.

In my very first music class our teacher had us sing “God Bless America,” while she tinkled away on her slightly off-key piano. As early fall sunlight streamed through the tall grimy windows of the music appreciation room, slanting dusty bars of golden light illuminated our efforts to mouth the lyrics. Unfortunately for me, one of those revealing bars of light illuminated my lips, which had remained closed throughout the duration of the song. My failure to participate did not go unnoticed.

“Myron,” the teacher inquired, “has the cat got your tongue?”

“No, ma’am,” I managed to get out.

“Let’s do it over,” she said to the class, “so Myron can join in.”

I tried, I surely did, but after only a few bars the piano died, and with it my public school singing career.

“Myron,” the teacher said ever so gently, “from now on you will be in charge of the most important element in the overall success of our chorus.”

And with that she placed in my hands a piece of metal in the shape of a triangle.

“What’s this?” I asked. “It looks like a triangle.”

“

Exactly,

” she exclaimed. “How clever of you to understand so quickly.”

From that moment on I was never to sing a single note. Instead I stood at the rear of the chorus, holding my triangle by a string grasped in one hand while striking it gently, pretty much as the mood struck me, with a slim metal wand held in the other. Of course, the occasional slight tinkles of sound were drowned out by the robust voices of my classmates.

“Practice,” my teacher instructed me after presenting me with the triangle. “Practice makes perfect,” she added, and sent me home with the triangle without another word.

To do what?

I wondered.

To practice,

I surmised.

And so it was that I proudly climbed the three flights of stairs that afternoon, triangle held carefully under my arm, steel wand safely in my pocket. Greeting my mother and brother at the door to our apartment, I waved the triangle at them, very full of myself.

“I’m a musician,” I signed to her, while also announcing it out loud to my brother. “My teacher said I’m the most important part of our chorus.”

“That’s nice,” my mother, a daughter of the Great Depression, signed right back. “Sit. You look hungry. I’ll make you both some matzoh brei.”

“But I have to practice. My teacher said so.”

“Eat first—you’ll have more strength to practice,” she signed emphatically, her hands moving away from her chest, turning into fists.

My mother always said that her theory about life was that any problem could be faced, and overcome, with nothing more than a full stomach.

That evening, as usual, my father came home with the day’s newspaper under his arm.

“There is much to talk about,” he signed dramatically to my brother and me. “The news today is exciting.”