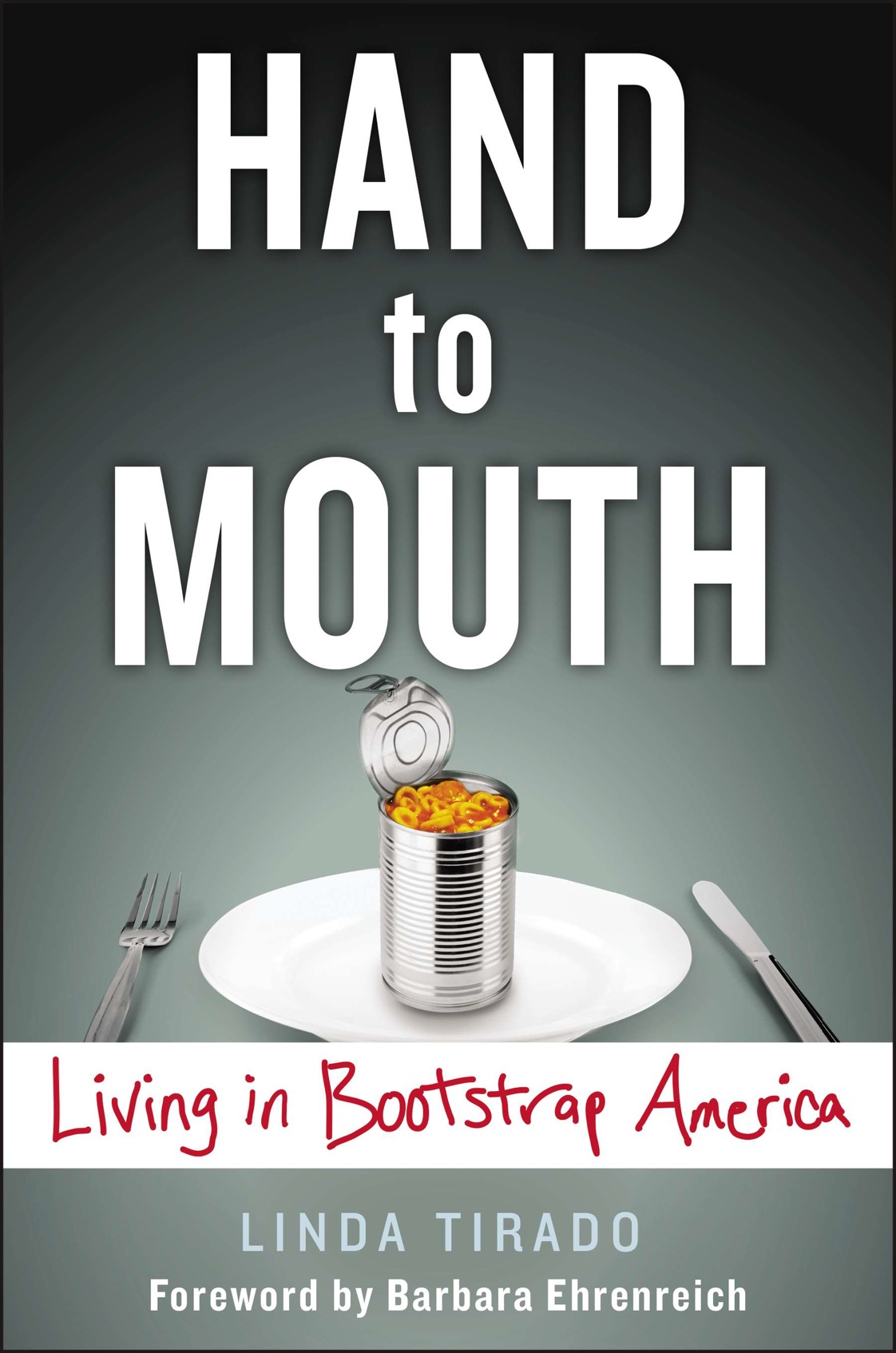

Hand to Mouth: Living in Bootstrap America

Read Hand to Mouth: Living in Bootstrap America Online

Authors: Linda Tirado

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness, #Social Classes

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Publishers Since 1838

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia • New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Linda Tirado

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

ISBN 978-0-698-17528-0

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone.

Version_1

For Tom, who can’t say I didn’t warn him

Foreword by Barbara Ehrenreich

3

You Can’t Pay a Doctor in Chickens Anymore

4

I’m Not Angry So Much as I’m Really Tired

5

I’ve Got Way Bigger Problems Than a Spinach Salad Can Solve

7

We Do Not Have Babies for Welfare Money

9

Being Poor Isn’t a Crime—It Just Feels Like It

10

An Open Letter to Rich People

By Barbara Ehrenreich

I

’ve been waiting for this book for a long time. Well, not this book, because I never imagined that the book I was waiting for would be so devastatingly smart and funny, so consistently entertaining and unflinchingly on target. In fact, I would like to have written it myself—if, that is, I had lived Linda Tirado’s life and extracted all the hard lessons she has learned. I am the author of

Nickel and Dimed

, which tells the story of my own brief attempt, as a semi-undercover journalist, to survive on low-wage retail and service jobs. Tirado is the real thing.

After my book came out in 2001, I spent over ten years on the road talking about it at union conferences, church gatherings, and mostly on college campuses. I did this partly for the money because I had lost my best-paying journalistic job in 1997, and then a few years later the media decided that writers no longer needed to be paid at all, as if writing involves no caloric expenditure whatsoever.

But I also did it because I was on a mission. People often asked how my work for

Nickel

and Dimed

changed me, and I think they meant how did it make me, as a middle-class person, more aware of the poor. Well, I didn’t need that much more awareness since I was born into the lower rung of the working class and managed to re-land in it by becoming a single mother and then marrying a warehouse worker when I was in my thirties. So my stint as a low-wage worker/journalist had only one major effect on me: It moved me from concern about the exploitation of low-wage workers—to something more like rage.

I had expected to experience material deprivation in my life at $7 an hour (the equivalent of about $9 today), and I certainly did. The fact that I had some built-in privileges like a working car (I got a Rent-A-Wreck in each of the cities where I worked so I wouldn’t end up writing a book about waiting for buses) only made the deprivation part more shocking. Here I was—in good health, with no small children in my care—working full-time, sometimes more than one job at time, sometimes to the point where my legs felt like rubber, and I was living in a dump and dining at convenience stores or Wendy’s.

What I had not expected was the daily humiliation, the insults and what seemed like mean-spirited tricks. To be poor is to be treated like a criminal, under constant suspicion of drug use and theft. It means having no privacy, since the boss has the legal right to search your belongings for stolen items. It involves being jerked around unaccountably, like the time Wal-Mart suddenly changed my schedule, obliterating the second job I had lined up. It means being ordered to “work through” injuries and illness, like the debilitating rash I once acquired from industrial-strength cleaning fluids.

And what was most amazing to me: Being a low-wage worker means being robbed by the very employer who is monitoring

you

so insistently for theft. You can be forced to work overtime without pay or made to start working forty-five minutes before the time clock starts ticking. If you do the math, you may find that a few more hours have been shaved off your paycheck each week by the corporation’s computers.

But when I made my way from campus to campus, telling my stories about work and urging students to take an interest in all the low-wage workers who were making their education possible every day—the food service workers, janitors, clerical workers, and adjunct faculty—I was invariably asked the question that boils down to: What’s wrong with these people? Meaning the workers, not their bosses.

Typically, the questioner would be a frat boy who had taken Econ 101, a course which exists, as far as I can see, for the sole purpose of convincing young people that the existing class structure is just, fair, and unchangeable anyway. If there’s nothing wrong with our economic arrangements, then the only remaining question is: Why do “these people” have children, lack savings, fail to go to college, eat junk food, smoke cigarettes, or whatever else is imagined to be holding them back?

So when I came across Linda Tirado’s blog about six months ago, I felt an enormous wave of vindication. Even—or, perhaps, especially—her admission that she smokes cigarettes hit me like a gust of fresh air. She tells what it’s like to be a low-wage worker for the long term, with an erratically employed husband and two small children to raise and support. She makes all the points I have been trying to make in my years of campaigning for higher wages and workers’ rights: That poverty is not a “culture” or a character defect; it is a shortage of money. And that that shortage arises from grievously inadequate pay, aggravated by constant humiliation and stress, as well as outright predation by employers, credit companies, and even law enforcement agencies.

But let me get out of the way now. She can tell this so much better than I can.

I

n the fall of 2013, I was in my first semester of school in a decade. I had two jobs; my husband, Tom, was working full-time; and we were raising our two small girls. It was the first time in years that we felt like maybe things were looking like they’d be okay for a while.

After a particularly grueling shift at work, I was unwinding online when I saw a question from someone on a forum I frequented:

Why do poor people do things that seem so self-destructive?

I thought I could at least explain what I’d seen and how I’d reacted to the pressures of being poor. I wrote my answer to the question, hit post, and didn’t think more about it for at least a few days. This is what it said:

WHY I MAKE TERRIBLE DECISIONS, OR, POVERTY THOUGHTS

There’s no way to structure this coherently. They are random observations that might help explain the mental processes. But often, I think that we look at the academic problems of poverty and have no idea of the why. We know the what and the how, and we can see systemic problems, but it’s rare to have a poor person actually explain it on their own behalf. So this is me doing that, sort of.

Rest is a luxury for the rich. I get up at 6 a.m., go to school (I have a full course load, but I only have to go to two in-person classes), then work, then I get the kids, then I pick up my husband, then I have half an hour to change and go to Job 2. I get home from that at around 12:30 a.m., then I have the rest of my classes and work to tend to. I’m in bed by 3. This isn’t every day, I have two days off a week from each of my obligations. I use that time to clean the house and soothe Mr. Martini and see the kids for longer than an hour and catch up on schoolwork. Those nights I’m in bed by midnight, but if I go to bed too early I won’t be able to stay up the other nights because I’ll fuck my pattern up, and I drive an hour home from Job 2 so I can’t afford to be sleepy. I never get a day off from work unless I am fairly sick. It doesn’t leave you much room to think about what you are doing, only to attend to the next thing and the next. Planning isn’t in the mix.

When I was pregnant the first time, I was living in a weekly motel for some time. I had a minifridge with no freezer and a microwave. I was on WIC. I ate peanut butter from the jar and frozen burritos because they were 12/$2. Had I had a stove, I couldn’t have made beef burritos that cheaply. And I needed the meat, I was pregnant. I might not have had any prenatal care, but I am intelligent enough to eat protein and iron whilst knocked up.

I know how to cook. I had to take Home Ec to graduate high school. Most people on my level didn’t. Broccoli is intimidating. You have to have a working stove, and pots, and spices, and you’ll have to do the dishes no matter how tired you are or they’ll attract bugs. It is a huge new skill for a lot of people. That’s not great, but it’s true. And if you fuck it up, you could make your family sick. We have learned not to try too hard to be middle class. It never works out well and always makes you feel worse for having tried and failed yet again. Better not to try. It makes more sense to get food that you know will be palatable and cheap and that keeps well. Junk food is a pleasure that we are allowed to have; why would we give that up? We have very few of them.

The closest Planned Parenthood to me is three hours. That’s a lot of money in gas. Lots of women can’t afford that, and even if you live near one you probably don’t want to be seen coming in and out in a lot of areas. We’re aware that we are not “having kids,” we’re “breeding.” We have kids for much the same reasons that I imagine rich people do. Urge to propagate and all. Nobody likes poor people procreating, but they judge abortion even harder.

Convenience food is just that. And we are not allowed many conveniences. Especially since the Patriot Act passed, it’s hard to get a bank account. But without one, you spend a lot of time figuring out where to cash a check and get money orders to pay bills. Most motels now have a no-credit-card-no-room policy. I wandered around SF for five hours in the rain once with nearly a thousand dollars on me and could not rent a room even if I gave them a $500 cash deposit and surrendered my cell phone to the desk to hold as surety.

Nobody gives enough thought to depression. You have to understand that we know that we will never not feel tired. We will never feel hopeful. We will never get a vacation. Ever. We know that the very act of being poor guarantees that we will never not be poor. It doesn’t give us much reason to improve ourselves. We don’t apply for jobs because we know we can’t afford to look nice enough to hold them. I would make a super legal secretary, but I’ve been turned down more than once because I “don’t fit the image of the firm,” which is a nice way of saying “gtfo, pov.” I am good enough to cook the food, hidden away in the kitchen, but my boss won’t make me a server because I don’t “fit the corporate image.” I am not beautiful. I have missing teeth and skin that looks like it will when you live on B

12

and coffee and nicotine and no sleep. Beauty is a thing you get when you can afford it, and that’s how you get the job that you need in order to be beautiful. There isn’t much point trying.

Cooking attracts roaches. Nobody realizes that. I’ve spent a lot of hours impaling roach bodies and leaving them out on toothpick spikes to discourage others from entering. It doesn’t work, but is amusing.

“Free” only exists for rich people. It’s great that there’s a bowl of condoms at my school, but most poor people will never set foot on a college campus. We don’t belong there. There’s a clinic? Great! There’s still a copay. We’re not going. Besides, all they’ll tell you at the clinic is that you need to see a specialist, which, seriously? Might as well be located on Mars for how accessible it is. “Low-cost” and “sliding scale” sound like “money you have to spend” to me, and they can’t actually help you anyway.

I smoke. It’s expensive. It’s also the best option. You see, I am always, always exhausted. It’s a stimulant. When I am too tired to walk one more step, I can smoke and go for another hour. When I am enraged and beaten down and incapable of accomplishing one more thing, I can smoke and I feel a little better, just for a minute. It is the only relaxation I am allowed. It is not a good decision, but it is the only one that I have access to. It is the only thing I have found that keeps me from collapsing or exploding.

I make a lot of poor financial decisions. None of them matter, in the long term. I will never not be poor, so what does it matter if I don’t pay a thing and a half this week instead of just one thing? It’s not like the sacrifice will result in improved circumstances; the thing holding me back isn’t that I blow five bucks at Wendy’s. It’s that now that I have proven that I am a Poor Person that is all that I am or ever will be. It is not worth it to me to live a bleak life devoid of small pleasures so that one day I can make a single large purchase. I will never have large pleasures to hold on to. There’s a certain pull to live what bits of life you can while there’s money in your pocket, because no matter how responsible you are you will be broke in three days anyway. When you never have enough money it ceases to have meaning. I imagine having a lot of it is the same thing.

Poverty is bleak and cuts off your long-term brain. It’s why you see people with four different babydaddies instead of one. You grab a bit of connection wherever you can to survive. You have no idea how strong the pull to feel worthwhile is. It’s more basic than food. You go to these people who make you feel lovely for an hour that one time, and that’s all you get. You’re probably not compatible with them for anything long term, but right this minute they can make you feel powerful and valuable. It does not matter what will happen in a month. Whatever happens in a month is probably going to be just about as indifferent as whatever happened today or last week. None of it matters. We don’t plan long term because if we do we’ll just get our hearts broken. It’s best not to hope. You just take what you can get as you spot it.

I am not asking for sympathy. I am just trying to explain, on a human level, how it is that people make what look from the outside like awful decisions. This is what our lives are like, and here are our defense mechanisms, and here is why we think differently. It’s certainly self-defeating, but it’s safer. That’s all. I hope it helps make sense of it.

While I was thinking that maybe a couple of people would read my essay, lightning struck. A lot of people started to share it. Someone suggested that I submit it for posting on the main page of the website we hung out on. That wasn’t uncommon, so I did. The next thing I knew, the world had turned upside down. The Huffington Post ran my essay on its front page,

Forbes

ran it,

The Nation

ran it.

After the original piece went viral, I got a lot of emails from people who told me that they did not agree; they did not cope in the same ways. That’s fair, and true. Keep it in mind. What was neither fair nor true was the criticism I received inferring that I was the wrong sort of poor. A lot of this criticism seemed to center on the fact that I was not born into poverty, as though that were the only way someone might find herself unable to make rent. And yet we have a term for it: downward mobility. We have homeless PhDs and more than one recently middle-class person on food stamps. Poverty is a reality to more people than we’re willing to admit.

Overall, though, the response was overwhelmingly one of solidarity. I got thousands of emails from people saying that they understood exactly what I was trying to describe, that they felt the same way. They told me their stories—the things that bothered them and how they were dealing with life. It’s not just me who feels this way, not by a long shot. Poor people talk about these things, but no one’s listening to us. We don’t usually get a chance to explain our own logic. The original piece that you just read, and this book, are simply that: explanations. I am doing what I can to walk you through what it is to be poor. To be sure, this is only one version. There are millions of us; our experiences and reactions to them are as varied as our personalities and backgrounds.

I haven’t had it worse than anyone else, and actually, that’s kind of the point. This is just what life is for roughly a third of the country. We all handle it in our own ways, but we all work in the same jobs, live in the same places, feel the same sense of never quite catching up. We’re not any happier about the exploding welfare rolls than anyone else is, believe me. It’s not like everyone grows up and dreams of working two essentially meaningless part-time jobs while collecting food stamps. It’s just that there aren’t many other options for a lot of people.

In fact, the Urban Institute found that half of Americans will experience poverty at some point before they’re sixty-five. Most will come out of it after a relatively short time, 75 percent in four years. But that still leaves 25 percent who don’t get out quickly, and the study also found that the longer you stay in poverty, the less likely it becomes that you will ever get out.

Most people who live near the bottom go through cycles of being in poverty and being just above it—sometimes they’re just okay and sometimes they’re underwater. It depends on the year, the job, how healthy you are. What I can say for sure is that downward mobility is like quicksand. Once it grabs you, it keeps constraining your options until it’s got you completely.

I slid to the bottom through a mix of my own decisions and some seriously bad luck. I think that’s true of most people. While it can seem like upward mobility is blocked by a lead ceiling, the layer between lower-middle class and poor is horrifyingly porous from above. A lot of us live in that spongy divide.

I got here in a pretty average way: I left home at sixteen for college, promptly behaved as well as you’d expect a teenager to, and was estranged from my family for over a decade. I quit college when it became clear that I was taking out loans to no good effect; I wasn’t ready for it yet. I chased a career simply because it was the first opportunity available rather than because it was sensible.

And I also had medical bills. I had bouts of unemployment, I had a drunken driver total my car. I had everything I owned destroyed in a flood.

So it’s not just one or the other: nature or nurture, poor or not poor. Poverty is a potential outcome for all of us.

This is a huge societal problem, and we’re just starting to come to grips with all the ways that a technological revolution and globalization have vastly increased inequality. You cannot blame your average citizen for those things. Nor can you blame individual companies—it is how we, collectively, have decided to do things.

We got here partially because of bad policy decisions and partially because of factors nobody could have foreseen. Telling an individual company to do better is a lot like telling an individual poor person to save more—true and helpful, but not so easy in practice. Most companies, like most people, aren’t the top 1 percent. They are following the market, not driving it. Besides which, any asshole with money can buy and run a company. They’re not all smart enough to figure out long-term investments in human capital.

I am not, for all my frustration, opposed to capitalism. Most Americans, poor ones included, aren’t. We like the idea that anyone can succeed. What I am opposed to is the sort of capitalism that sucks the life out of a whole bunch of the citizenry and then demands that they do better with whatever they have left. If we could just agree that poor people are doing the necessary grunt work and that there is dignity in that too, we’d be able to make it less onerous.

Put another way: I’m not saying that

someone

doesn’t have to scrub the toilets around here. All I’m saying is that maybe instead of being grossed out by the very idea of toilets, you could thank the people doing the cleaning, because if not for them, you’d have to do it your damn self.

In this book I have been careful to obscure identifying details about people. Most of the people I’ve worked for have long since turned over themselves and work elsewhere now. Just in case, however, I have changed places, personal details, and names as needed to protect people’s privacy. Nobody, myself included, thought that I’d be writing a book.