Grumbles from the Grave (8 page)

Read Grumbles from the Grave Online

Authors: Robert A. Heinlein,Virginia Heinlein

Tags: #Authors; American - 20th century - Correspondence, #Correspondence, #Literary Collections, #Letters, #Heinlein; Robert A - Correspondence, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #20th century, #Authors; American, #General, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Science Fiction, #American, #Literary Criticism, #Science fiction - Authorship, #Biography & Autobiography, #Authorship

Bear in mind that my advice to you is based on a law, specifically intended by the Congress under the Constitution to restrict the freedom of speech of civilians in wartime in their relations with the military. If you don't like the law, write to your congressman about it. If you feel you must express yourself, write it down and save it until the war is over—but

don't

tell a member of the armed forces that his superiors are stupid and incompetent. Don't write to Ron [L. Ron Hubbard] in such a vein. He has not my indoctrination and he

is

in the battlefield. If you feel that the high command is incompetent, take it up with your congressman and your senators. Those of us in the service must work under the officers that are placed over us—it doesn't help to try to shake our confidence in them.

* * *

. . . I've dug down into my personal funds many times to entertain visiting congressmen, visiting notables, etc. There are no funds appropriated for such things; the commissioned officers pay for them themselves. Naval officers act as scout masters for sea scouts. They are always available to speak before any body of persons willing to listen—travel to and from at his own expense, or charged to ship's service (a

private

fund) by his CO. We always have had public relations officers and we always have done everything we knew how to do to foster goodwill for the navy. In addition to that, the naval affairs committees of both houses are kept constantly informed in detail of the needs of the navy and the strategic reasons therefor.

Our efforts were pitifully inadequate. How could they be adequate? In the first place, we aren't advertising men and we don't know how. In the second place, even if we knew how, we had no appropriations to work with. All we could do was to talk, and that got us damned little newspaper space and no billboards. Of course, we could get an occasional scholarly article published—much good that did!

. . . You may consider my reaction as a type form professional reaction; it derives from my orientation and indoctrination. It is quite evident from the suggestion you made and your answer to my reaction that you have not the slightest understanding of the psychology of a professional military man. I don't know quite how to explain this. It is a heavily emotional matter and goes back to some basic evaluations. Let me put it this way: Take a young boy, before he has been out in the business world. Put him into the naval academy. Tell him year after year that his most valuable possession and practically his only one is his personal honor. Let him see classmates cashiered for telling a small and casual lie. Let him see another classmate cashiered for stealing a pair of white silk socks. Tell him that he will never be rich but that he stands a chance of having his name inscribed in Memorial Hall. Entrust him with secrets. Indoctrinate him so that he will consider himself locked up and unable to move simply because his sword has been taken away from him. Feed him on tales of heroism. Line the corridors of his recitation halls with captured flags. Shucks, why go on with it—I think you must see what I am driving at. That will produce a naval officer, a man you can depend on to be utterly courageous in the face of personal danger regardless of the sick feeling in his stomach, but it won't produce an advertising man.

Naval officers, as a group, are no more temperamentally capable of producing the kind of sensational publicity you suggest they produce than they are of sprouting wings and flying.

Furthermore, if they were, they would be no damn good as naval officers. A naval officer is much more than a man with a certain body of technical information. He is a man trained to respond in a certain behavior pattern in which "honor" and "service" have been substituted for economic motivation. I don't know whether I have convinced you or not, but I can assure you that it would be almost impossible to find an officer who has spent his entire adult life in the fleet who could put over the sensationalism you suggest. It is about like asking a priest to desecrate the sacrament.

* * *

Certainly the navy has specific secrets. In peacetime they are limited to such things as the details of weapons (and occasionally the existence of a weapon), codes and ciphers, the numerical details of gunnery scores, the insides of certain instruments, and similar details in which we are

trying

to keep a little ahead of the next. You spoke of "official spies" being shown things which are kept from the public. Who handed you that piece of guff? I know what you mean—foreign officers. Unless they are allies, they don't see anything that newsreel men don't see. I remember once being ordered to chaperone a British naval officer. I was admonished never to let him out of my sight and was given a list of things he must

not

see. I even went into the head with him. . . .

Of course, in wartime practically everything is secret—and a damned good thing! But the essential matters on which a civilian could make up his mind whether or not we need a big navy aren't secret, never have been secret, and by their nature can't be secret. Geographical strategy, for example, and the relative strengths of the fleets of various nations.

Jane's Fighting Ships

is not a particularly reticent book, and I know you have seen it. Navy yards aren't hard to get into. In normal times, naval vessels run boats for any visitor who wants to come aboard—and the ship's police has a weekly headache to make sure none get into the fire-control stations and similar places.

I am completely bewildered as to what you mean by the "hush hush" attitude of the navy. I would certainly appreciate some facts.

Lots of civilians are necessarily entrusted with certain naval secrets. I've sailed with many a G.E., Westinghouse, and AT&T engineer. The gadget of mine that was taken over by the fleet was developed by one of your father's engineers. I doubt if he personally had any occasion to know about it, but don't ask him about it and don't try to conjecture what it might be. Don't mention it to anyone, lest they do a little guessing. By mentioning the

class

of engineer that developed it I have shown greater confidence in you than I have in any other civilian. Let it stand that it is a proper military secret and that we hope that we are the only navy using it.

It is quite possible that a request for a piece of information is turned down when the questioner can see no reason why it should not be told. To that I can say only that the officers refusing to part with the information are the only possible judges as to whether or not public welfare is involved. Being human, they can make errors of judgment,

hut no one can judge for them.

Obviously—if you hold a secret, I have no way of judging whether or not you should share it with me. Consequently, the responsibility for the decision rests entirely with you. A perfectly innocent request for information can be met with what appears to be an arbitrary refusal. How can the questioner know?

But, having been in the navy, and having held both confidential and secret information, I can assure you that it is not the policy of the navy to go out of its way to be mysterious. Decidedly not! On the contrary, it usually seemed to me that we were too frank, aboveboard, and open. It was too easy to get too close to really hush-hush stuff, to such an extent that it used to worry me.

* * *

Item: You excuse the somewhat wild remarks of yourself, [Fletcher] Pratt, and company, on the basis that you are sore as hell, especially so as you are navy fans and love ships. (Incidentally, you don't seem to want to be classed as part of the general public, yet seem to resent being advised to act like professionals in the matter.) If you think you're sore and upset, how do you think I feel? Pearl Harbor isn't a point on a floor game to me—I've been there. The old

Okie

isn't a little wooden model six inches long; she's a person to me. I've sketched her fuel lines down in her bilges. I was turret captain of her number two turret. I have been in her main battery fire control party when her big guns were talking. Damn it, man, I've

lived

in her. And the casualty lists at Oahu are not names in a newspaper to me; they are my friends, my classmates. The thing hit me with such utter sickening grief as I have not experienced before in my life and has left me with a feeling of loss of personal honor such as I never expected to experience. For one reason and one only—because I found myself sitting on a hilltop, in civilian clothes, with no battle station and unable to fight, when it happened.

* * *

Editor's Note: Robert wrote stories for John W. Campbell, Jr. for

Astounding

and

Unknown

for close to three years. When Pearl Harbor was attacked in 1941, Robert tried to persuade the Navy to take him back on active duty. Failing in that, he went to work in Philadelphia doing engineering at the Naval Air Experimental Station.

The war over, Robert looked around at the wider horizons for his writing career. Four short stories were sold to the

Saturday Evening Post

, then the most important and highest paying market, and he sold his first juvenile novel to Charles Scribner's Sons. The next market he tackled was motion pictures, and the successful

Destination Moon

resulted.

"Gulf" was the only story Robert wrote after World War II which was intended solely for the

Astounding

market. Occasionally his agent, Lurton Blassingame, would send a novel to John W. Campbell, Jr. Some of those were rejected for various reasons with lengthy letters of explanation from John Campbell to Robert. Those stories were never intended for that market, but Campbell would explain why the writing and stories were terrible— from his viewpoint. When Podkayne

[Podkayne of Mars]

was offered to him, he wrote Robert, asking what he knew about raising young girls in a few thousand carefully chosen words.

The friendship dwindled, and was eventually completely gone. It was just another casualty, probably, of World War II.

CHAPTER III

THE SLICKS AND THE SCRIBNER'S JUVENILES

TRY AT SLICKS

(38)

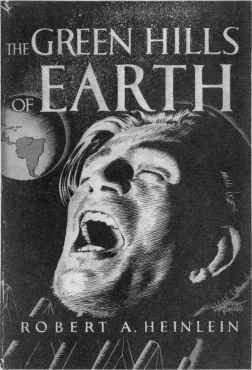

The Green Hills of Earth

book cover—a story first serialized in the

Saturday Evening Post,

February 8, 1947.

(39)

Heinlein choosing a magazine in Ojai (north of Ventura) around 1947.

October 25, 1946: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

The news that you sold "The Green Hills of Earth" to the

Saturday Evening Post

is very gratifying for more reasons than the size of the check. I am happy that we have cracked the top slick market; I am particularly happy that it was done with this story, as it is a favorite of mine which has been growing in my mind for five years.

Editor's Note: In the 1930s and 1940s and farther back, the

Saturday Evening Post

was the elite market of the short story writer. It paid the highest rates and carried the most prestige.

The

Post

was on every newsstand, and was widely read.

In addition to short stories, and serialized novels, it also ran many articles. To be well-informed, one read the

Post

. It was sold everywhere; the covers by Norman Rockwell were especially featured. Each issue contained some articles, short fiction, and usually a series of stories concerning much the same cast, and it was the ambition of every short story writer to have one of these series going. Bonus rates were paid for such series.

Selling the

Post

was a boy's job, and boys would go from door to door selling the Post, with two companion magazines,

The Ladies Home Journal

, and

Country Gentleman

. One of Robert's first jobs as a child was being a P-J-G boy.

The

Saturday Evening Post

carried a column about the authors who appeared in each issue. The column was called "Keeping Posted," and Robert was asked for material about himself and a picture. Because it was his first appearance in the

Post

with "The Green Hills of Earth" he was included in that column.

. . . sending you on Monday another interplanetary short, intended for slick (the

Post,

I hope)—the domestic troubles of a space pilot, titled either "For Men Must Work" or "Space Pilot" ["Space Jockey"]. It took me a week to write it and three weeks to cut it from 12,000 to 6,000 [words]—but I am beginning to understand the improvement in style that comes from economy in words. (I set it at 6,000 because a careful count of the stories in recent issues of the

Post

shows that the shorts average a little over 6,000 and are rarely as short as 5,000.)