Grumbles from the Grave (39 page)

Read Grumbles from the Grave Online

Authors: Robert A. Heinlein,Virginia Heinlein

Tags: #Authors; American - 20th century - Correspondence, #Correspondence, #Literary Collections, #Letters, #Heinlein; Robert A - Correspondence, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #20th century, #Authors; American, #General, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Science Fiction, #American, #Literary Criticism, #Science fiction - Authorship, #Biography & Autobiography, #Authorship

Stranger.

It is a work of fiction in parable form. It is not a "put-on" unless you choose to classify every work of fiction as such. Who are these persons who allege this? I would like an opportunity to face up to one or more of them . . . as this allegation has come back to me often enough to cause me to think that someone has been spreading it systematically and possibly with malice. But the allegation always reaches me at least secondhand and never with the name of the person. Will you tell me where

you

got this allegation? I would like to track down this "Scarlet Pimpernel" and get him to hold still long enough to ask him what he is up to and why.

Now, for some background on

Stranger

and my stories in general: I write for the following reasons—

1. To support myself and my family;

2. To entertain my readers;

3. And, if possible, to cause my readers to

think.

The first two of these reasons are indispensable, and constitute, together, a commonplace market transaction. I have always had to work for a living, for myself and now for my dependents, and I come from a poor, country family—root, hog, or die. I have worked at many things, but I discovered, somewhat by accident, that I could produce a salable commodity—entertainment in the form of fiction. I don't know why I have this talent; no other member of my family or relatives seems to have it. But I got into it for a reason that many writers have—it was what I could do at the time, i.e., I have been ill for long periods throughout my life, and writing is something a person can do when he is not physically able to take a 9-to-5 job. (Someday I would like to find time to do an essay on this. The cases range from blind Homer to consumptive R. L. Stevenson and are

much

more numerous than English professors seem to be aware of.)

But if a writer does not entertain his readers, all he is producing is paper dirty on one side. I must always bear in mind that my prospective reader could spend his recreation money on beer rather than on my stories; I have to be aware every minute that I am competing for beer money—and that the customer does not have to buy. If I produced, let us say, potatoes or beef, I could be sure that my product had some value in the market. But a story that the customers do not enjoy reading is worth

nothing.

So, when anyone asks me why I write, if it is a quick answer, standing up, I simply say, "For money." Any other short answer is dishonest—and any writer who forgets that his prime purpose is to wangle, say 95 cents out of a customer who

need not buy at all

simply does not get published. He is not a writer; he just thinks he is.

(Oh, surely, one hears a lot of crap about "art" and "self-expression," and "duty to mankind"—but when it comes down to the crunch, there your book is, on the newsstands, along with hundreds of others with just as pretty covers—and the customer does not have to buy. If a writer fails to entertain, he fails to put food on the table—and there is no unemployment insurance for free-lance writers.)

(Even a wealthy writer has this necessity to be entertaining. Oh, he could indulge in vanity publication at his own expense—but who reads a vanity publication? One's mother, maybe.)

That covers the first two reasons: I write for money because I have a household to support and in order to earn that money I must entertain the reader.

The third reason is more complex. A writer can afford to indulge in it

only

if he clears the first two hurdles. I have written almost every sort of thing—filler paragraphs, motion picture and TV scripts, poetry, technical reports, popular journalistic nonfiction, detective stories, love stories, adventure stories, etc.—and I have been paid for 99% of what I have written.

But most of the categories above bored me. I had enough skill to make them pay but I really did not enjoy the work. I found that what I did enjoy and did best was speculative fiction. I do not think that this is just a happy coincidence; I suspect that, with most people, the work they do best is the work they enjoy.

By the time I wrote

Stranger

I had enough skill in how to entertain a reader and a solid enough commercial market to risk taking a flyer, a fantasy speculation a bit farther out than I had usually done in the past. My agent was not sure of it, neither was my wife, nor my publisher, but I felt sure that I would sell at least well enough that the publisher would not lose money on it—would "make his nut."

I was right; it did catch hold. Its entertainment values were sufficient to carry the parable, even if it was read strictly for entertainment.

But I thought that the parables in it would take hold, too, at least for some readers. They did. Some readers (many, I would say) have told me that they have read this fantasy three, four, five or more times—in which case, it can't be the story line; there is no element of surprise left in the story line in a work of fiction read over and over again; it has to be something more.

Well, what was I trying to

say

in it?

I was asking questions.

I was

not

giving answers. I was trying to shake the reader loose from some preconceptions and induce him to think for himself, along new and fresh lines. In consequence, each reader gets something different out of that book

because he himself supplies the answers.

If I managed to shake him loose from some prejudice, preconception, or unexamined assumption, that was all I intended to do. A rational human being does not need answers, spoon-fed to him on "faith"; he needs questions to worry over—serious ones. The quality of the answers then depends on

him

. . . and he may revise those answers several times in the course of a long life, (hopefully) getting a little closer to the truth each time. But I would never undertake to be a "Prophet," handing out neatly packaged answers to lazy minds.

(For some of the more important unanswered questions in

Stranger

see chapter 33, especially page 344 of the hardcover, the paragraph starting: "All names belong in the hat, Ben.")

Starship Troopers

is loaded with unanswered questions, too. Many people rejected that book with a cliché—"fascist," or "militaristic." They can't read or won't read; it is neither. It is a dead serious (but incomplete) inquiry into

why

men fight. Since men

do

fight, it is a question well worth asking.

My latest book,

I Will Fear No Evil

, is even more loaded with serious, unanswered questions—perhaps too laden; the story line sags a little. But the questions are dead serious—because, if they remain unanswered, we wind up dead. It does not affect me personally too much, at least not in this life, as I will probably be dead before the present trends converge in major catastroohe. Nevertheless, I worry about them. I think we are in a real bind . . . and that the answers are not to be found in simplistic "nature communes," nor in "Zero Population Growth," which does not embrace the entire globe. There may be no answers fully satisfactory . . . and even incomplete answers will be very difficult.

I find that I have written an essay to myself rather than a letter. Forgive me—perhaps I have reached the age at which one maunders. But I hope I have convinced you that

Stranger

is dead serious . . . as

questions.

Serious, nontrivial questions, on which a man might spend a lifetime. (And I almost have.)

But anyone who takes that book as

answers

is cheating himself. It is an invitation to think—not to believe. Anyone who takes it as a license to screw as he pleases is taking a risk; Mrs. Grundy is not dead. Or any other sharp affront to the contemporary culture done publicly—there are stern warnings in it about the dangers involved. Certainly "Do as thou wilt is the whole of the Law" is correct when looked at properly—in fact, it is a law of nature, not an injunction, nor a permission. But it is necessary to remember that it applies to everyone—including lynch mobs. The Universe is what it is, and it never forgives mistakes—not even ignorant ones . . .

AFTERWORD

Before the cut version of

I Will Fear No Evil

was ready for publication, Robert was taken ill. For two years he was laid up with various illnesses and operations. At last, in 1972, he was well enough and very eager to begin writing again. His next book was

Time Enough for Love.

In addition to changes in the times and customs, Robert now had a reputation that allowed him to do such books as he preferred to do. It is possible that, at least in part,

Stranger

had had some effects upon the sexual revolution of the sixties and seventies. It was in tune with the moods of the times. So his publishers did not object to the length of

Time Enough for Love

, and one thing I found curious—there was no objection at all to the incest scenes. Not even reviewers mentioned it.

The following two years were mostly taken up with study of advances in physical and biological sciences. How could one write science fiction without keeping up with what was being discovered in those fields? These studies were undertaken for two articles for the

Britannica Compton Yearbook:

"Dirac, Antimatter and You," and "Are you a 'Rare Blood.' "

Another serious illness occurred in 1978. Following his recuperation from that, Robert went to his computer and wrote

The Number of the Beast.

Aside from a very few flags on the copy-edited manuscript, he was asked to cut by 2,000 words (!) out of an estimated 200,000 words. That was, of course, an easy task.

Expanded Universe

followed, at the behest of James Baen. To our surprise, this book generated far more mail than any other book Robert had ever written. For two years, I was tied to the computer answering the fan mail which resulted from its publication.

In 1981, at seventy-four years of age, Robert decided that he would no longer do any of the special little tasks which being a well-known writer entails: no more speeches (even to librarians), no more appearances at conventions—his health would not permit the pressure. He would simply write the books he wanted to write.

So he wrote

Friday,

then

Job

,

The Cat Who Walks through Walls

, and his final book,

To Sail Beyond the Sunset

. Each of these books differed from anything he had previously done, and some displayed new techniques he had been inventing.

To Sail

was published on Robert's 80th birthday in 1987, by special arrangement with his publisher. The only further item Robert wrote was the foreword for Ted Sturgeon's novel

Godbody

. While contract negotiations for

To Sail

were still going on, Robert came down with what was to be his final illness. For almost two years, he hovered between illness and frail health, but finally succumbed on May 8, 1988.

(249)

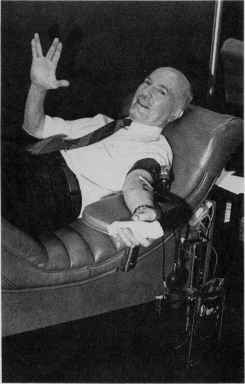

In 1977, Heinlein organized a major blood drive among science fiction fans.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A

CUTS IN

Red Planet

[Alice Dalgliesh, the editor at Scribner's, objected to anything that might be construed as having some sexual connotations and also to the use of guns by youngsters, as well as other matters. As a result, Heinlein was forced to make a number of cuts in his original manuscript. Some of these are shown here. Chapter and paragraph numbers refer to

Red Planet

as originally published.]

Between Chapter II, paragraph 13 and Chapter II, middle of paragraph 23:

The second generation trooped out. Phyllis said, "Take the charges out of your gun, Jimmy, and let me practice with it."

"You're too young for a gun."

"Pooh! I can outshoot you." This was very nearly true and not to be borne; Phyllis was two years younger than Jim and female besides.

"Girls are just target shooters. If you saw a water-seeker, you'd scream."

"I would, huh? We'll go hunting together and I'll bet you two credits that I score first."

"You haven't got two credits."

"I have, too."

"Then how was it you couldn't lend me a half credit yesterday?"

Phyllis changed the subject. Jim hung up his weapon in his cupboard and locked it. Presently they were back in the living room, to find that their father was home and dinner ready.

Phyllis waited for a lull in grown-up talk to say, "Daddy?"

"Yes, Puddin'? What is it?"

"Isn't it about time I had a pistol of my own?"

"Eh? Plenty of time for that later. You keep up your target practice."

"But, look, Daddy—Jim's going away and that means that Ollie can't ever go outside unless you or mother have time to take him. If I had a gun, I could help out."

Mr. Marlowe wrinkled his brow. "You've got a point. You've passed all your tests, haven't you?"

"You know I have!"

"What do you think, my dear? Shall we take Phyllis down to city hall and see if they will license her?"

Before Mrs. Marlowe could answer Doctor MacRae muttered something into his plate. The remark was forceful and probably not polite.

"Eh? What did you say, Doctor?"

"I said," answered MacRae, "that I was going to move to another planet. At least that's what I meant."