Greece, the Hidden Centuries: Turkish Rule From the Fall of Constantinople to Greek Independence (23 page)

Authors: David Brewer

Tags: #History / Ancient

11

Venetian Crete

V

enice held Crete for four and a half centuries, much longer than any of its other possessions among the islands of the Mediterranean or on the mainland of Greece. In the division of territories in 1204 after the fall of Constantinople to the Fourth Crusade, Crete had gone to Boniface of Montferrat, ruler of Thessalonika, who sold it to Venice for 1,000 marks. But Genoa too coveted Crete, and in 1206 Genoese raiders seized the unfortified town of Iráklion and other Cretan territory, their leader Enrico Pescatore styling himself ‘Dominus Creti’. After several unsuccessful attempts Venice finally ejected the Genoese in 1211, the start of continuous Venetian rule of Crete.

In the first two centuries of Venetian rule barely a decade passed without a Cretan revolt of some kind. Some Greek historians tend to lump these together, seeing them all as struggles for an unspecified freedom, and as expressions of national consciousness, a concept that acquired meaning only in the eighteenth century. Their argument can even become circular: the leaders of revolts had nationalist sentiments, therefore the revolts must have been inspired by nationalism, therefore the leaders must have had nationalist sentiments.

In fact there were many causes for these revolts. Some were simply low-level conflicts that led to widespread violence, and were sparked by the Venetians seizing land, horses or other livestock, or by an alleged Venetian insult to a Cretan girl. Some were inspired or supported by Crete’s previous rulers the Byzantines, especially after the return of the Byzantine rulers to Constantinople in 1261, whose aim, never achieved, was to reunite Crete with the Byzantine Empire. A major revolt of 1363 had yet other origins: it was an attempt by the Venetians in Crete to break away from Venice and to form an independent Venetian Crete. The revolt was known as the rebellion of Áyios Títos, a tribute both to its Venetian leader Titus Venier and to the island’s patron saint, who had supposedly been charged by St Paul with bringing Christianity to Crete. But within a year a Venetian fleet had restored the authority of the metropolis.

None of these revolts achieved any lasting result, and they were sometimes followed by savage Venetian reprisals. Many, however, ended with Venetian grants of privileges to the Cretans, or confirmation of existing

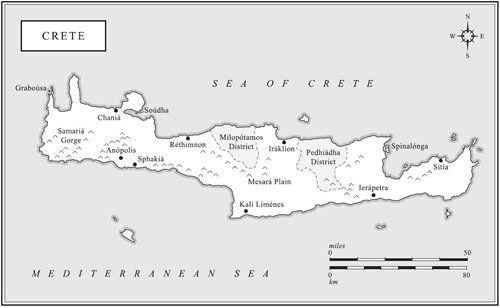

privileges. A significant such grant came at the end of the long revolt of 1282–99, led by the wealthy landowner Aléxios Kalléryis. The revolt was centred on the district of Milopótamos between Réthimnon and Iráklion, but spread to most of western Crete. In previous risings Kalléryis had sometimes supported rebels against the Venetians, sometimes Venetians against rebels, and his aim now was not to expel the Venetians – they were preferable as rulers, he believed, to Genoese or Catalans – but to carve out a semi-independent principality for himself under Venetian rule.

The Kalléryis revolt dragged on inconclusively until 1296 when a Genoese fleet attacked western Crete, captured Chaniá, and invited Kalléryis to join them. Kalléryis refused and this paved the way for the agreement of 1299, known as the Pax Alexii Callergi, which ended the revolt. Kalléryis himself did well out of the peace: estates he had lost were returned to him and new ones granted. There were some benefits too for the people of Crete. The different classes – nobles, their children and so on down the scale – were recognised and made permanent, so that nobody could be deprived of his status. It was promised that a Greek Orthodox bishop would be appointed for the first time, the choice to be agreed between Kalléryis and the Catholic archbishop. But though the agreement of 1299 is sometimes presented as a great advance for the people of Crete, the main beneficiary was undoubtedly Kalléryis himself. He was later referred to as the ruler (

avthéntis

) of Crete, and his

name was inscribed in the Libro d’Oro of Venetian nobility, a unique privilege for a Cretan.

Though the Kalléryis revolt was centred on the prosperous northern region of Milopótamos, the most persistent cause of trouble to the Venetians was the rugged mountainous region round the port of Sphakiá, to which today’s visitors, with aching knees, are returned by boat after descending the Samariá gorge. The men of Sphakiá were formidable fighters, and remained so, showing the same qualities outstandingly against the Germans in the 1940s. The Venetians held them in high regard, and in 1602 the Venetian provveditor-general wrote of them: ‘They surpass all the other inhabitants of these parts. This is not only because they are manly in appearance, competent and agile with muscular bodies, robust, proud, daring and courteous in manner. What most distinguishes them is their keenness of spirit, their greatness of soul, and their unrivalled ability to handle arms, whether bow or musket, in which they are exceptional. That ultimately is why they are without doubt the most daring, the most virile and the noblest of the men on this island.’

1

The Venetian officials administering Crete were, from the beginning, essentially the same as those that Venice later established in Cyprus, and reflected the system in Venice itself. The head of the administration was a Venetian noble based in Iráklion with the title of Duke of Crete, assisted by two counsellors. Subordinate to them were the captains of each of Crete’s regions, initially six and later reduced to four. Military command was exercised by the captain-general, and each of Crete’s fortresses had its own commander. Superior to all of these, including the Duke of Crete, was the provveditor-general, at first appointed only intermittently in times of crisis but from 1569, when the Turkish threat to Cyprus had become obvious, the office was made permanent.

Both the provveditor-general and the Duke of Crete were appointed in Venice and sent out to Crete for only two years. Venice persisted with this policy in both Crete and Cyprus in spite of its obvious drawbacks. Probably this was in part because Venice was afraid that long-standing colonial administrators would build themselves a threatening power base, partly because candidates would not want to neglect for too long their political careers in Venice – and several provveditors-general later became Doge. The system has been a boon to historians because departing officials were required to leave on record a report on the island and recommendations for improvements. But the inevitable short-termism of the arrangement is clear from the protest of the citizens of Iráklion in 1629 against a proposed new water supply. Besides claiming that it was impractical and unaffordable, they objected that the time left for

the current provveditor was too short to finish the scheme, and that no provveditor ever completed his predecessor’s projects but preferred to start his own.

Venice had secured possession of Crete in 1211, and in the following years established control of the island through granting military fiefs to Venetians. These fief-holders were granted land that had been taken from local landowners or the Church, and in return had to provide troops, cavalry if the fief-holder was of a noble Venetian family and infantry if not. This was the near-universal system of both Christian and Ottoman rule in the period before standing armies became established. In the first century of Venetian rule an estimated 10,000 Venetians were settled in Crete.

From about 1500 this system began to break down. Cretans were displacing Venetians by buying fiefs or subdivisions of them, and they began to occupy posts in the island’s administration. By 1600 only 164 of the 964 fiefs in the Iráklion region were held by Venetians, the remaining four fifths by Cretans. In 1575 the reforming provveditor-general Giacomo Foscarini reported that most of these supposed providers of cavalry neither owned a horse nor knew how to ride, and when required to show their military credentials would simply borrow horses and put villagers on them. People gathered to watch this ridiculous display and threw rotten fruit and stones at the riders. Thus of the two aims of the fief system – to provide Venetian dominance of the island and the means to defend it – neither was any longer being achieved.

This movement, from initial Venetian dominance to later fusion of Venetian and Cretan interests, also happened in the relations between the Venetians and the Orthodox Church. At the start Venice abolished the Orthodox bishoprics, and the bishopric promised in 1299 after the Kalléryis revolt seems to have been short lived, if it was established at all. This meant that Orthodox priests had to go abroad to be ordained, either to the Venetian possessions in the Ionian islands where, curiously, Orthodox bishops were permitted, or to Ottoman territory. Some Orthodox priests were thought to practise without being ordained at all. But there was no ban on Orthodox churches, and by the seventeenth century there were 113 Orthodox churches on Crete and only 17 Catholic ones. In 1602 the provveditor-general Benedetto Moro wrote that Catholics and Orthodox often went to each other’s churches, and that Venetian officials should make a point of attending Orthodox services to show solidarity with the Cretans. He also ruled that Catholic priests must not preach against Orthodoxy. In many ways the island had become – to borrow the title of one of the best books on Venetian and Ottoman Crete – a shared world.

A remarkable expression of these shared values was the so-called Veneto-Cretan renaissance of the last century of Venetian rule. In literature the most famous figure was Vitséntzos Kornáros, author of the

Erotókritos

, a romance in verse of nearly 10,000 lines from an Italian source but with the action transferred to ancient Athens. Anachronistically the poem contains a fight between a Cretan and a Turk, perhaps a reference to the battle of Lepanto. Of the Cretan artists of the period even the more prominent are little known outside Greece, with one exception: Dhoménikos Theotokópoulos, known as El Greco.

El Greco was born in 1541 in Iráklion, where he served his artistic apprenticeship. One of his earliest known works, perhaps an examination piece for joining the guild of painters, is of St Luke, the patron saint of artists, painting an icon of the Virgin and Child. The icon is in the traditional Byzantine style while the depiction of St Luke and his studio are Italianate. El Greco was already blending the Byzantine past with the west European present.

El Greco was well established as an artist when at the age of 26 he left Crete for Venice. There he was strongly influenced by Titian and Tintoretto, and his ‘The Purification of the Temple’ painted while in Venice is wholly Italian in style. Three years later he moved to Rome, where he added Michelangelo to his list of exemplars. But his stay in Rome was a mere eighteen months, and in 1572 he moved to Spain.

He went first to Madrid, where he produced among other works ‘The Adoration of the Name of Jesus’, an allegory of the battle of Lepanto, commissioned by Philip II. The name of Jesus, IHS for Jesus Hominum Salvator, is blazoned in the sky. Kneeling in adoration on the left are Philip II dressed in black, the Pope and the Doge of Venice, the trio representing the victorious Holy League. On the right the damned – the infidel Turks – are in torment at the mouth of Hell.

2

However, El Greco soon lost favour with the King, and by 1577 he was in Toledo, where he spent the last decades of his life. Some of his works were realist, such as the portrait of which the sitter said that his soul was at a loss to choose between his real body and his painted semblance. But it was in Toledo that El Greco developed the unique personal style of brilliant colours combined with the ‘purposeful distortion and pulling of planes’.

3

El Greco died in Toledo in 1614, in relative poverty after many disputes over payment for his work. He was virtually forgotten until well into the nineteenth century, when he came to be recognised as a forerunner of the Impressionists and their successors: ‘Cézanne and El Greco are spiritual brothers,’ wrote the artist Franz Marc.

4

Picasso borrowed from El Greco for his ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’. Perhaps the

best summary of El Greco’s work was by an early appreciator of it, the critic Théophile Gautier, who wrote in 1845: ‘There are abuses of light and dark, of violent contrasts, of singular colours, extravagant attitudes, draperies are shattered and crumpled haphazardly; but in all that there presides a depraved energy, an unhealthy strength that betrays the great painter and the madness of Genius.’

5

Until the late flowering of the Veneto-Cretan renaissance, education in Venetian Crete had been patchy at best. In the early period of Venetian rule in the fourteenth century some schools existed, and popular verses from this time express the moans of schoolboys throughout the ages. One wanted vocational not academic training:

I didn’t learn a cobbler’s trade, a shipwright’s or a quilter’s,

At school I learnt – oh my poor head! – just Greek and Latin letters.