Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (58 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

But now the Bhangi colony and its environs had been swamped by refugees, many of them disposed to blame Gandhi for their fate, so it was considered only prudent for him to be reinstalled in Birla House, the industrialist’s spacious, high-ceilinged mansion on one of New

Delhi’s broad new boulevards, with its deep, carefully tended garden. He was no stranger to the challenge of maintaining his regime of austerity in surroundings of luxury. Birla House had been his Delhi base for most of the two decades before he was inspired to move in with the Bhangis. On September 16, a week after he arrived in Delhi, he returned to the neighborhood of the Bhangi colony for a meeting with a right-wing extremist group that drilled on the banks of the Jamuna nearby. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, or RSS, had been blamed for much of the violence; it later would be banned in the crackdown on Hindu extremists following Gandhi’s assassination. But instead of condemning them on this last encounter, the Mahatma tried to find common ground as one Indian patriot speaking to others in the cause of civil peace. His session that day with the RSS—which has taken in recent decades to mentioning his name in its daily roll call of Hindu heroes—was supposed to be followed by a prayer meeting.

But rowdy Hindu hecklers made prayers impossible. “

Gandhi murdabad!

”—“Death to Gandhi!”—they

cried, after an attempt was made to read verses from the Koran, a standard part of his ecumenical ritual. Thereafter, for the next four and a half months, his prayer meetings were held in the presumed security of Mr. Birla’s walled garden, where finite crowds could be infiltrated and closely watched by plainclothesmen. Today mansion and garden are preserved as the Gandhi Smriti, the scene of the Mahatma’s martyrdom.

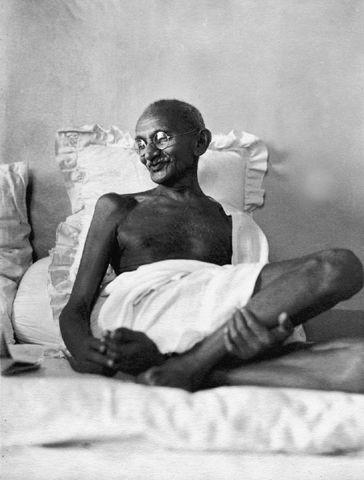

At ease on a frilly Birla House pillow, 1942

(photo credit i12.1)

The Bhangi colony also has its Gandhi shrine today. Bhangis don’t go by that disparaged name anymore. They prefer to call themselves Balmikis (sometimes, in Roman letters, spelled Valmikis) after an ancient saint, Rishi Balmiki (or Valmiki), the mythical author of the

Ramayana

, the Hindu epic, whom they claim as an ancestor and now semideify; or so the figure of the holy man in the small temple hard by the reconstructed Gandhi house seems to suggest. To approach the temple, visitors must remove any footwear. To enter the Gandhi house—or, for that matter, approach the point in the Birla garden where he fell—they must do the same. Perhaps, despite his clearly expressed wishes, his status as something more than a human may still be evolving. Birla House is a major tourist stop. The former Bhangi colony is seldom visited, except at election time when Congress politicians call. But Gandhi’s portrait is freshly garlanded there on a regular basis as it is in few other Dalit quarters, if any, across the subcontinent today. Meanwhile, the Balmikis live in four-story cream and maroon concrete apartment houses put up by the state, with cute little balconies attached to each apartment.

When Gandhi stayed there, the quarter was isolated; now its residents have ready access to one of the stations of Delhi’s new metro. Mostly, they’re still sweepers, drawing something better than starvation wages from the New Delhi Municipal Corporation. But only former Balmikis, the renamed Bhangis, seem to live in these unofficially segregated quarters. The best that can be said is that while their circumstances have obviously improved, their status seems to be evolving in an Indian way with glacial slowness, more than six decades after Gandhi lived among them.

Despite his displacement from the Bhangi colony, Gandhi continued to preach against untouchability in the final four months of his life, a theme second only in his discourse in this time to his harping on the need for Hindus to give up their retaliation against Muslims. “

Anger is short madness,” he told them, imploring them “to stay their hands.” A tour of

Hindu and Muslim refugee camps in which no latrines had been dug and the stench of human excrement was unavoidable instantly reignited the revulsion he’d felt in Calcutta in 1901, in Hardwar in 1915, only this was now 1947 and India was supposed to be free. “

Why do [the authorities] tolerate such stink and stench?” he demanded to know. They should insist that the refugees clean up after themselves. “We must tell them that we would give them food and water but not sweepers,” he said. “I am a very hard-hearted man.”

His prayer meetings, broadcast nightly on the radio for fifteen minutes, became a diurnal part of life in the still-seething capital. A whole lifetime later, it’s not easy to gauge the impact of these broadcasts. They didn’t attract huge numbers to the prayer meetings in the Birla garden, where the actual crowds, usually in the hundreds, were small compared with the massive throngs of Hindus and Muslims that had turned out to hear him weeks earlier in Calcutta.

Jawaharlal Nehru, installed as India’s first prime minister, came to sit with him every evening in the relatively small chamber Gandhi occupied on the ground floor, just off a stone patio where he sunned himself after his baths, wearing a broad-brimmed straw peasant’s hat that had been given to him in

Noakhali. The routine of Nehru’s visits left an impression that the old man was being consulted on urgent problems. Left unclear was how much guidance he offered, how likely it was to be heeded.

“

They are all mine and also not mine,” he said of his old colleagues, now in power, who were sending troops to

Kashmir, a measure he couldn’t approve but wouldn’t deplore. A

spinning wheel, a small writing desk, and a thin mattress that folded up during the day were his only possessions of any size in that room. An exhibit case now displays smaller items he kept there, which were notable for their paltriness: wire-frame eyeglasses and their case, a metal fork and spoon, a wood fork and spoon, a knife, a pocket watch, and his walking stick.

He stuck to his causes—discoursing on peace and the desirability of Hindustani as a national language, even the best way to handle compost—and stuck to his daily schedule, rising hours before daybreak for prayers, his walk, meal, bath, enema, and massage. As always, that was the time for him to start in on his correspondence before receiving visitors, Muslim and Hindu, who brought him their sense of Delhi’s mood, how near to the surface violence still lurked. What he heard was seldom encouraging. Muslims were still fleeing, and few Hindus were willing to lift a finger, despite his pleas, to make them feel wanted, let alone safe. His own mood reverted to the intermittent uncertainty darkening

to despair that had weighed on him in Srirampur. “

These days, who listens to me?” he said in his third week back in Delhi. “Mine is a lone voice … I have come here and am doing something but I feel I have become useless now.”

On October 2, 1947, the last birthday of his life, turning seventy-eight, he said he didn’t look forward to another one. “

Ever since I came to India,” he said, “I have made it my profession to work for communal harmony … Today we seem to have become enemies. We assert that there can never be an honest Muslim. A Muslim always remains a worthless fellow. In such a situation, what place do I have in India and what is the point of my being here?” He doesn’t know whether to blame himself or the Hindus of Delhi. At one moment he says the citizens of Delhi must have gone mad; at another he wonders aloud, “

What sin must I have committed that [God] kept me alive to witness all these horrors?”

As the weeks wear on, his mood, if anything, becomes steadily more lugubrious, even though the level of outright violence, in Delhi at least, falls off. “

On the surface things are sufficiently nice,” he writes to Rajagopalachari in Calcutta, “but the under-current leaves little hope.” Two weeks later he informs a prayer meeting that 137 mosques have been grievously damaged or destroyed in Delhi alone, some of them turned into Hindu temples. This is sheer irreligion, he scolds, not in the least excused by the fact that Hindu temples have been converted into mosques in Pakistan. Three weeks after that, he’s still on a tear. “

Misdeeds of the Hindus in [India] have to be proclaimed by the Hindus from the roof-tops,” he says, “if those of the Muslims in Pakistan are to be arrested or stopped.” The dispossessed Hindu refugees and Hindu chauvinists show little sign of being shamed by this fierce Jeremiah in their midst. On the contrary, some of them are easily roused against him, as Gandhi has seen.

India has now been free and independent for about four months. And the leading shaper of that independence remains unsettled and despairing. In the early days of 1948 he broods on the thought that since he’d obviously failed to meet the first half of his injunction to himself to “do or die” in Delhi, it’s time for him to test the second.

No single catastrophe served as catalyst for his decision to start his

seventeenth and final fast on January 13. In the days running up to the fast, he’d been forcefully struck by several indications that matters were on a downward slide. First he received a detailed account of rampant corruption at all levels of the newly empowered Congress movement in the Andhra region of southeastern India. Then some nationalist Muslims asked him

to help them emigrate from India to Britain now that it had become clear that they could find no secure place in either India or Pakistan. What a destination for nationalists at the end of their struggle, Gandhi remarks. Finally, Shaheed Suhrawardy, who’d been attempting informal mediation with Jinnah in consultation with Gandhi and who, until that point, had left the Mahatma with the impression that he still considered himself an Indian, now told him that he didn’t feel safe moving around Delhi, even by car.

Suhrawardy, who’d been told by Jinnah that he was turning into Gandhi’s stooge, returned from Karachi with a request on Pakistan’s behalf. He asked Gandhi to intercede to unfreeze Pakistan’s share of British India’s assets that the new Indian government was bound by treaty to pay, a considerable sum by the standards of the time (500 million rupees, about $145 million at prevailing exchange rates). Gandhi’s increasingly disgruntled follower Patel—who was least inclined to follow him on issues touching Muslims—had convinced the cabinet that the money should be withheld pending a settlement on questions such as

Kashmir; otherwise, he argued, the assets might be used to buy arms and ammunition.

Mountbatten, now the governor-general, had also brought the issue to Gandhi’s attention, thereby infuriating Patel, who said the Englishman had no right to lobby against a cabinet decision. Neither the former viceroy nor the former chief minister had any way of imagining that Gandhi’s interest in the issue of the assets, which they had stoked, could prove fatal.

Announcing the fast at his prayer meeting on January 12, the Mahatma mentioned the insecurity of Muslims and the Congress’s corruption but not the blocked payment to Pakistan. “

For some time my helplessness has been eating into my vitals,” he said. “It will end as soon as I start a fast … I will end the fast when I am convinced that the various communities have resumed their friendly relations, not because of pressure from outside but of their own free will.” But on the second day of the fast, the cabinet convened at Birla House, beside a string bed on which the old man was lying, for reconsideration of the frozen assets issue. An aggrieved Patel, momentarily convinced that he was the target of his leader’s fast, complained bitterly to Gandhi, then left for Bombay on the fast’s third day, though the Mahatma by then had visibly weakened. “

Gandhiji is not prepared to listen to me,” he’s reported to have said. “He seems determined to blacken the names of the Hindus before the whole world.”

Confronted with the charge that his fast was on behalf of Muslims and

against Hindus, Gandhi readily conceded that it was basically true. “

All his life he had stood, as everyone should stand, for minorities and those in need,” he said, according to the transcript of his talk that he authorized following the prayer meeting on the first evening of the fast.

The timetable here is vital, for it meshes fatefully and finally locks into the crude cogs of a Hindu extremist plot being pursued with amateurish zeal in the city of Poona, near which the British had imprisoned Gandhi three times for a total of six years. Now with the departure of the British, he could be caricatured there as an enemy of Hindustan.

By his assassin’s own testimony, it was Gandhi’s announcement of his fast on the twelfth that had lit the fuse on the plot he and his main accomplice hatched starting that night; and it was the declaration three days later that the cabinet had reversed itself and decided to transfer the blocked reserves to Pakistan, explaining that it was moved by a desire “to help in every way open to them in the object which Gandhiji has in heart,” that had clinched the secret verdict of the conspirators condemning him to death.

Patel’s absence from Delhi, meanwhile, would ensure that the

Home Ministry was without firm leadership. “Every condition given by [Gandhi] for giving up the fast is in favor of Muslims and against the Hindus,”

Nathuram Godse would later testify at the trial where he was finally sentenced to hang for what he represented as a patriotic imperative. Among Gandhi’s conditions had been the return to Muslim custody of the mosques that had been attacked, desecrated, and turned into Hindu temples.