Grantville Gazette, Volume 40 (16 page)

Read Grantville Gazette, Volume 40 Online

Authors: edited by Paula Goodlett,Paula Goodlett

Alicia interrupted. "A lot of people think there will be a war with Saxony next year. Won't claiming Saxon jurisdiction be seen as disloyal?"

"It's the Saxon church that's claiming ecclesiastical jurisdiction, not the Saxon government claiming legal jurisdiction," Markus explained. "There

is

a difference, even though in Saxony, the Lutheran church is the state church."

Horst shifted in his seat. "As much as I don't like Pankratz Holz, it wouldn't be fair to accuse him of being disloyal to the USE just because his theological allies are in Saxony. We Catholics get accused of disloyalty because the pope is in Italy, and a lot of people see the wars as primarily a conflict between Catholics and Protestants. Usually by people like Holz, so it just kills me to defend him on this."

"Well said," Joseph told him.

"I want to expand on what Markus said," Johannes Musaeus declared. "

Holz

is claiming that Tilesius' consistory has issued this proclamation as binding on all Lutherans under their jurisdiction, but we're pretty sure that's not the case. There's a lot of 'Lutherans ought not to associate with' in this document, and not nearly as much 'and we'll throw you out if you do' as Holz claims there is. We think that this is actually Tilesius's starting position for the next colloquy, the one we'll have to have after the war with Saxony. So this proclamation isn't the Lutheran church speaking, and it's not going to be recognized as binding by anyone outside Holz's congregation. Probably even Tilesius intends it as points for debate rather than orders.

"That leads to the other central point. Since there is no consistory above Holz, he can do what he wants. If he wants to insist that no one in his congregation do business with non-Lutherans and enough of the congregation goes along with it, he can probably kick you out."

"Just like Deacon Underwood caused the general Anabaptists to leave First Baptist Church," Joseph said. "It's abuse of authority but it's an internal matter. Part of not being in a state church means that the government doesn't get involved in internal church matters. To West Virginia County and the State of Thuringia-Franconia, it's no different than if the Elks and the Moose decided that their members couldn't do business with members of the other organization."

Katharina nodded to herself. The Engelsbergs had left First Baptist with the other general Anabaptists—those who believed that Christ died for the sins of everyone. The particular Anabaptists had stayed because they actually agreed with Deacon Underwood that Christ died specifically for the sins of the elect. Dr. Green had put forward the proposition that Christ's death was sufficient for all but efficient only for the elect and had taken heat from both sides for his trouble. It was too bad that Joseph and Marta didn't go to the same church she did anymore. At least they were getting some good teaching from Joe Jenkins, even though he had turned over as much teaching and preaching as possible to the Anabaptist elders. But Johannes was saying something important.

". . . the other hand, since Holz isn't under a consistory, none of the Lutheran churches in Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt or Jena are going to pay attention to his proclamation. His congregation is effectively an independent Lutheran church. Ecclesiastically, it's no different than First Baptist or First Methodist. It is a church of one congregation. Holz has effectively done what Herr Lambert advised the Flacians to do back at the Rudolstadt Colloquy. What that means for you, Herr Neustatter, is that you and your employees can attend any other Lutheran church. St. Martin's in the Fields is the closest. Pastor Kastenmayer is a Philippist but there are a number of Flacians who attend. They're waiting for St. Thomas's to open."

"Ah, St. Thomas the Apostle Lutheran Church," Guenther said.

"You sound skeptical," Neustatter observed.

"Well, there is a reason it is already called Doubting Thomas Lutheran Church," Markus admitted. "But Johannes is right. And next Sunday there will be one more family of Flacians at St. Martin's. Mine." He looked around the table.

"Thank you," Neustatter said. "I think that's probably where we will be, also. Wolfram and Stefan's families will probably find that most comfortable under the circumstances."

"Herr Neustatter," Johannes said. "I feel bound to point out that your excommunication of Pastor Holz isn't ecclesiastically valid. You're not actually allowed to do that."

Neustatter smiled. "But I already did. And as you've pointed out, Holz's congregation is an independent church. Schwarzburg and Jena have no jurisdiction to tell me whether I can excommunicate the pastor or not."

Katharina struggled to keep from smiling. Johannes clearly hadn't thought of that.

"I'm pretty sure Martin Luther wasn't technically supposed to excommunicate the pope, either," Neustatter continued. "But he did."

A few members of the

Bibelgesellschaft

squirmed in their seats. But none of them said anything. The bell rang.

"Astrid tells me she hired you as a credit against the next time you need security specialists," Neustatter said. "If that is still acceptable?"

The students exchanged glances. Mattheus Beimler, the BGS treasurer, answered. "That'll be fine."

Neustatter nodded. "We may need to consult with you again in a week or two."

They shook hands all around. After Neustatter and Astrid had left, Katharina's brother Georg observed, "A lot can happen in one day in Grantville. Even a cold day like yesterday."

****

Catrin's Calling

Written by Kerryn Offord

July 4, 1634, on the Saale River near Saalfeld

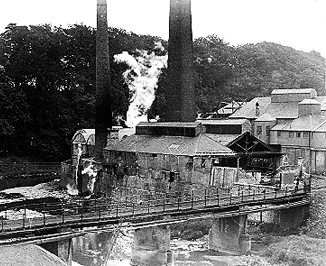

The Spengler paper mill was lit up like a Christmas tree, making it very easy for Catrin Schmoller to find her way as the evening twilight turned to night. Her knock on the door was greeted by the last person she wanted to see her arrive at the party on her own.

"Hello, beautiful. Better late than never. You do realize the party started at eight, not nine." Friedrich Stisser looked beyond Catrin as if he was expecting to see someone else. "What have you done with Andreas?"

This was exactly why Catrin would have preferred someone else had answered the door. Anyone else might have inquired politely after Andreas, but not Friedrich. As a friend of Catrin's, he didn't seem to think he had to be polite to her. "He is at his home snuggled up to his radio transceiver, trying to make contact with a Radio League member in Amsterdam."

"And you wanting to attend Gottfried's thirtieth birthday celebration . . ."

"Yes!" The fact Andreas would rather miss her best friend's husband's birthday party than miss an evening with his radio waves had been the final nail in the coffin of a relationship that hadn't been progressing as Catrin would have preferred. "Andreas Rottenberger is history."

Friedrich put out a hand and condescendingly patted Catrin on the top of her head. "There, there, girl. Never mind, there are plenty more fish in the sea. You'll soon hook another."

She shot a hand up to stop Friedrich mussing her hair. "Your sympathy is overwhelming." She smiled as a suitable revenge occurred. "Maybe I should reward it by telling your betrothed the truth about you."

"Do your worst, little girl," Friedrich said with the smuggest of smug looks on his face.

"Oh, I will. You're forgetting that Gottfried tells Veronika

everything

." She waited for Friedrich to realize the import of that statement. "You still want me to do my worst?"

No longer looking quite so smug, Friedrich tugged Catrin toward a table where drinks were laid out. "There's no need to be nasty. Besides, you're well rid of Andreas. Didn't I hear that you claimed to know more about radio than he did?"

"I might have," she admitted. "Why is it guys think they understand how something works just because they're male? Can't they see the advantages of learning from someone else's mistakes?"

"So Andreas is another who doesn't read the instruction manual?"

"Yes he is, and I'm going to make sure my next boyfriend is one of those rare males who have no trouble with reading the manual before things go wrong. I've had it with guys who treat instruction manuals as a port of last resort."

"I wish you luck," Friedrich muttered as he guided Catrin towards their hostess.

Grantville-Kamsdorf railroad, Late July, 1634

Mikkel Agmundson was bored. He'd been dragooned into accompanying his father and some of his business associates to the up-timer city of Grantville. That should have been interesting, but he'd been spending most of his time translating for the members of the party who didn't speak the local dialect. Right now he was staring out the window of the train traveling from Grantville to Saalfeld. That was another thing that should have been interesting, but he'd made the return trip from Grantville to the steel mills of Kamsdorf the other day and quickly learned that the train was just another boring means of transport. It was faster than a horse or a carriage, but that was all it had going for it. Now traveling in a car; that had been interesting. It was a great pity that they couldn't afford to take one back to Arendal with them.

He sort of perceived the structure—no doubt a mill of some kind—as the train took the gentle curve south, toward Saalfeld. That the mill was the only building on the river edge for the last half-mile had something to do with it attracting his roving eye, but not as much as the way the wind was playing with the skirt of the female watching men working around a pond by the mill. The closer the train got to the mill, the more Mikkel was able to absorb. It was definitely a young female, and quite a shapely one at that.

He sort of perceived the structure—no doubt a mill of some kind—as the train took the gentle curve south, toward Saalfeld. That the mill was the only building on the river edge for the last half-mile had something to do with it attracting his roving eye, but not as much as the way the wind was playing with the skirt of the female watching men working around a pond by the mill. The closer the train got to the mill, the more Mikkel was able to absorb. It was definitely a young female, and quite a shapely one at that.

"What on earth are they doing with those timbers?" Magnus Kristjanson asked from the seat opposite.

Mikkel didn't have to ask what timbers, because the woman was directing a couple of men hauling lengths of coppice timber from the pond. "I've no idea. Do you want to get off the train and ask?" Magnus shook his head, but Mikkel noted the way he continued to stare at the mill. "We can probably ask about the mill in Saalfeld," he suggested.

Magnus didn't answer, but Mikkel noticed that he didn't take his eyes off the mill until they crossed the River Saale and entered Saalfeld.

Council Office, Saalfeld

The sound of unfamiliar footsteps approaching the reception counter had Catrin pausing in her work to look up. Instantly she was entranced by the vision at the counter.

God, he was so cute

. She hurried over to the counter. "Can I help you?" she asked, fluttering her eye-lashes at the handsome hunk.

The older man beside the hunk seemed taken aback by Catrin's fluttering eyelashes, but the hunk seemed impervious. She sighed—situation normal. Just what was wrong with her that no normal cute guy seemed interested? Actually, she had a good idea what the problem was. One just had to look at Friedrich's betrothed. Barbara Rohrbacher was so well-endowed that she made the term grossly inadequate as a descriptor, while Catrin was, well, very much less well-endowed.

"We were wondering if you could tell us anything about the sawmill we passed on the train from Grantville," Mikkel asked after introducing himself and his companion.

That was the mill her best friend ran with her husband. A smile filled Catrin's face as she thought about that happy couple. "Spengler's isn't a sawmill. It's a paper mill."

"But paper is made from rag. We saw them carrying coppice logs into the mill," Mikkel protested.

"You can make paper from just about any plant fiber. It's just a matter of being able to reduce it to a suitable pulp. Gottfried Spengler uses ground wood for his paper. Although he'd much rather use chemically pulped wood, but he couldn't get enough wood to make it economic."

The younger man translated her comment to the elder, and then there was an intense conversation between them before the hunk turned back to Catrin.

"You seem to know a lot about this paper mill."

Catrin had learned a lot about making paper in the last year, and she wasn't afraid to demonstrate her knowledge, especially if it might impress a cute guy. "My best friend is married to Gottfried Spengler and I spend a lot of time over at the mill."