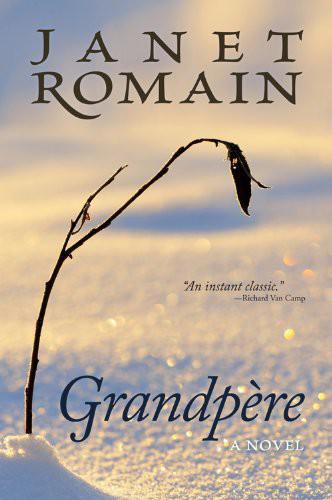

Grandpère

Authors: Janet Romain

Tags: #Fiction, #Families, #Carrier Indians, #Granddaughters, #Literary, #Grandfathers, #British Columbia; Northern

Grandpère

Janet Romain

Caitlin Press

Copyright © 2011 Janet Romain

First print edition © 2011 by Caitlin Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior

permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic

copying, a licence from Access Copyright, the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency,

www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777,

Caitlin Press Inc.

8100 Alderwood Road,

Halfmoon Bay, BC V0N 1Y1

www.caitlin-press.com

This story is fiction, and any resemblance to real people, places or

events is coincidental. Real places and events are used fictitiously.

Text design by Vici Johnstone.

Cover design by Michelle Winegar and Vici Johnstone.

Edited by Susan Mayse.

Cover photo Erkki Makkonen.

Epub by Kathleen Fraser.

Printed in Canada

Caitlin Press Inc. acknowledges financial support from the Government

of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the

Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Arts Council and the Book

Publisher’s Tax Credit.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Romain, Janet

Grandpère / Janet Romain.

ISBN 978-1-894759-69-4

I. Title.

PS8635.O4468G73 2011 C813’.6 C2011-900472-0

I dedicate this book to the ancestors, who sometimes whisper wisdom in my ears.

Chapter One

I have my pen and pad on my lap, ready. I smile at my Grandpère. He is so old and smaller than me now, his once brawny muscles shrunken away, but his wits are about him as clear as day. His dark eyes still twinkle. He sits in his favourite chair framed by sunlight streaming in through the window. His ever-present cane, which he always calls a walking stick, leans on the side of the chair. It’s covered with carvings of every animal in the bush. He is dressed in denim jeans held up by a flat-braided rope with its ends tasselled and beaded. His plaid bush jacket is tattered on the cuffs and looks as though it has seen better days, but he hasn’t worn the new one I bought for him and says this one is still good enough for now. It’s just like him, getting a little frayed on the edges.

I have promised to write some things down for him.

“Tell them,” he says. “Tell them, Anzel. Start with the people.” He pauses for a long time, closes his eyes and continues. “My childhood name was SiMon Wakim. It means Little Salt Brother. In English they named me Simon Walker. I still have that name.” He opens his eyes, smiles and nods.

“My people were a family of three brothers living in a village with their wives and children. We had four elders, three of them women and one man. The old people were still strong, but we all looked after them, making sure they had wood in the winter and food. We were happy.”

Grandpère is in storytelling mode, sitting up straight-backed in the chair, swaying gently back and forth with that look of detachment that tells me he is reaching somewhere for his words. His sentences are not coming out with the usual smooth flow that characterizes most of his stories. He loves to tell the old stories.

“We were living in the land of plenty,” he goes on. “Sometimes we were hungry but we never starved, and we always trusted a higher power would end our hunger. When it did, we always gave thanks, and the skinny times taught us to rejoice in the fat times.

“The people were safer then. There were no jails, but there was justice. There were no drunks. There was rarely any sickness. Everybody was good at something, and everyone fit in.

“At our gatherings we had speeches and dancing. It all was important.

“The families and the tribes knew their place in the world, but things changed very fast when white people and their God came into our land. Contact with white men made us grow up fast. Do or die. Many died. No one survived unchanged.

“My life has been witness to many changes. Some are good, some are bad.

“There are so many things to tell, Granddaughter.” He looks at me with faraway eyes. “I have to think for a while.” He smiles and closes his eyes. He was out with me early this morning in the garden and will probably sleep in the summer sun for a couple of hours, till lunch at least. I have such love for this old man. He looms through my life in all its seasons, his presence always so much larger than his frame, now that it’s shrunken in his late nineties, and very much still alive.

I leave him stretched out in his recliner in the breeze through the screen door, his hand on his walking stick, and go outside. The weeds in the garden are growing as fast as the young vegetables, and for the last two days I’ve been pulling them. There’s only one end of a row left to do, and I decide to finish it. The soil is warm, and the weeds come out easily. It is enjoyable to be out in the sun, and weeding feels more like play than work.

I come in a bit late to make a lunch of fried eggs and toast; it’s just going to take a minute. Grandpère is up already, sitting at the table. He mustn’t have slept long, since it takes him a while to walk from the living room to the table. Once I offered to get him one of those motorized wheelchairs, but he answered me with a look of utter scorn and told me that if he couldn’t walk from the window to the table, he would just as soon be dead. No arguing with that logic. No even mentioning it again.

He eats well, although lately he seems to do everything so slowly that I have a hard time adjusting. By the time I’ve cleaned the frying pan and counter, he’s done with his plate. “Thank you,” he says. “That was very good.” It doesn’t matter what kind of crazy meal I serve, he always says that. It always makes me feel good.

I take the eggshells and bread crusts out to the chickens. They scramble to grab the scraps, running with their snatched beakfuls to some quiet corner where they can eat without competition. Grandpère always leaves his crusts now. He says old men and babies don’t need to eat crusts. I don’t care. The chickens have never eaten as well as they have since he came here to live.

I bring in the eggs, seven today from just eleven chickens. It pleases me that these old hens are laying well. They have the run of the place, and out here in the country they are welcome companions, protected from the wild by the two guard dogs. A lot of coyotes and foxes in the bush are fond of chicken dinner, so Duke and Blue make it their business to patrol the yard. Duke is old, a husky-collie cross, and may be the best dog we’ve ever lived with. Blue is only three years old, a Pyrenees-heeler cross, and is the most peculiar looking dog. His coat is almost blue, his expression is comical and his energy is boundless. Duke and Blue are good company. We’re friends, these two giant dogs and I.

Going back to the house by the long path, I pass the garden. It’s glorious in its summer array. Over the years we filled it with perennial flowers from around the world, all blooming here in the centre of BC. The vegetables now take up the open places: spinach and young salad greens, radishes and green onions, all ready for the evening meal. Picking enough for a salad for me and Grandpère doesn’t take long, but I see a few more weeds to pull and flowers for a bouquet, so when I get back to the house, I’ve been gone over an hour. I put the greens in cold water in the sink, set the flowers in a vase and go to visit with him.

He is back in the easy chair. He beckons me over and points at the notepad, smiling. “I am going to tell you the things I want you to write,” he says. I grab my notebook and pen, and he begins.

“When I was young, before I knew your grandmother, I didn’t know that life could be any different than it was. The older men went down to the Fort twice a year. They traded furs for coffee, flour, sugar, axes, knives, bacon, bullets and beads. Sometimes they brought back hard curled candy. I sure liked that candy. My mother went once, but she never wanted to go again. She never said why. She always wanted beads. Everything that passed through her hands got beaded. She told her stories with beads. The circles were us, and they had the right colours for the directions. She put a little bit of herself in every design, and her beadwork was treasured among the family and the tribe.

“The year I got to go to the Fort was the first and last time. I went with my two uncles and my father, and my older sister came too. She was two winters older than me, but I was taller and stronger. We helped with the packs. Two of our three horses had died in the winter of that year, so we needed more people to pack the trade goods. We had to trade for horses too that year, and Sister carried a pack full of baskets and beadwork to trade for blankets and beads. The women also wanted a steel pot. We were so excited to go that we planned for days.

“How can I tell you what I felt when I saw the Fort? It was huge. We came out on the bank of the Mighty Big Lake, beside the River that Brought the Pinks. Across the water was the biggest village I had ever seen. One of the buildings was huge. It would have taken all of us many summers to put up that building, and even then, none of us would probably have slept upstairs. My Uncle Tree, my father’s oldest brother, said it was the new trading post they’d finished two summers before, after the old one burned down.

“We made camp on the beach and made a fire in the circle there. It was sandy and hot. We took off our moccasins and leggings and swam in the lake. We had fresh fish and eggs, and Sister made a fish soup with things she’d gathered up on the way. I can still taste that soup. It was like nothing that people make today. It has the flavour of my youth.

“In the afternoon a trade boat came over and got us. It was the biggest boat I had ever seen, and I was very happy to get to ride in it. We each took a paddle, my two uncles, my father and I. Sister crouched in the bottom with our trade bundles between three pairs of paddlers and the steering man at the end. The boat handled better than a small canoe with all that manpower on the paddles. We crossed the lake in a big arc around the river outlet so we didn’t get pulled into the current. Sister and I stared about even though we knew it was rude. We couldn’t help it and we realized that neither could the grown-ups.

“The men who came to get us could speak our language, not well but well enough to get by. One of them was named David. He had visited our village with his wife Louisa, whose sister was married to my cousin, and their daughter Clementine. My sister and Clementine were friends.

“David was happy to see us and invited us to camp the night in his lodgings. We took our packs to his place. He had a shed beside the lodgings with two big dogs, very wild, tied up to the door. We could not go to the shed till he moved the dogs, which were very quiet and gentle with him. We put our trade bundles in the shed except for the one my sister carried, and he retied the dogs.

“Their home was not made like our lodgings. It had a metal stove with a chimney and wood on the floors. The floor was covered with the nicest furs, the softest and best quality furs you would find anywhere, and Louisa cooked things we had never tasted before. My sister, Clementine and Louisa talked and giggled and played games with the little ones till they were all sleeping. Then the women curled up in a corner with the pack of things my mother and aunties had made. They told Sister how much each thing was worth and said they would help her trade. They made sounds of pleasure at everything in the pack. There were gifts for each of them in there.

“The men and I had a drink of whisky. My first, but it was sure not my last. My uncles had warned me it was a custom of the white man, and it was rude to refuse. They said it was like drinking horse piss, but it did not feel so bad once it was down. They said to only take one drink, for it was strong medicine that did not agree so well with our tribe, it was white-man medicine. I was not prepared for the warmth it spread through my body, nor the feeling of joy and appreciation that accompanied it. I found a love for my kin and even for Louisa’s man that night, which seemed to surpass all that I had felt before. If my uncles and father had not been there, I am sure I would have tried much more than one drink.

“The men talked about the winter — they had been trapping all winter — and they told tales of the animals and where they found them. At that time the names of the lakes and rivers were all different than now. I liked to listen to the stories. The talk of the men was a living history of our people. When Uncle Tree said he had been to the place where the people came over the neck, we knew it was the neck of the giant who had fallen long ago in a quarrel with another of his kind. We could see in our minds’ eyes the calm lake, the birch forest with the gigantic mountain peak behind stretching to the sky, mirrored behind with peak after peak making the giant’s spine. There was snow on top of those peaks in the heat of the summer days, when old man sun stayed in the sky for most of the day and night. How I would love to see that place again!

“The next day we woke up early. One of the small kids had been crying in the night and was hot and cranky in the morning. Louisa made some medicine and gave it to the child, and pretty soon he was sleeping. We went off to the big store where the trading was done.

“There were so many things in that store that I did not know what they were for. I was looking at some of them when a big white person dressed in very smooth clothes reached out and touched me on the hand. He moved in sign to say not to touch with my hands. I nodded and didn’t touch anything else, but I looked at everything. I did touch one blanket, very gently with the back of my hand, just to feel its softness. I wanted it for my mother.

“The trader was happy with the furs. He said ‘plenty big’ and ‘plenty soft’ at nearly every skin. He tasted the pemmican and said, ‘Very fresh, very good.’ Our men were smiling a lot, and Louisa’s man was helping them by saying the words in our language. The trading took nearly all day, but everyone seemed pleased when we got back to the house. The little one was still very hot, and Louisa took him down to the lake and bathed him in the cool water, then gave him some more sleeping medicine.

“We were in a hurry to start back, so the same men took us and our goods back across the lake. We caught the horse and took the other one that the men had traded for from the herd. No one had used that horse yet, but he knew the rope and followed our old mare willingly enough. He was one year old and a stud horse. My father said in the spring next year we would have one more horse, and I was glad to have more horses again. We slept there that night and in the morning we broke camp and headed back.

“Our loads were light on the way home, and we were full of stories of the things we had seen at the Fort. We had a big metal pot for my mother, and in it was the soft blanket I had touched in the store, wrapped around many small packets of beads and even some seashells that had been traded in from the coast. The thought of my mother’s joy made us all happy.

“We had two cases of bullets for both guns. They would last us a long time. Our mare’s packs were bulging with flour, sugar, coffee, ten pounds of dried apples and two sides of bacon. The apples were so good that we ate them with dry fish on the trail and never cooked a meal till we were home.

“All the men had traded for steel knives with cases that slid onto our waist belts. I must have pulled my knife out a hundred times on the trail home. The handle was bone, and it was mounted on the blade with two bolts. The nuts were recessed into the handle on the other side. To tighten the handle there was a slot on the bolt to turn it. I was fascinated and proud that I had such a fine knife.

“The trail home took us six days. We had such a party when we got home. Our uncles and Father laid out everyone’s things one by one, and no one was left out or disappointed. My mother shared her beads with all the women there, and every little girl had a fancy comb for her hair, and every little boy had a fold-up knife. The women cooked bannock, and we all drank coffee.