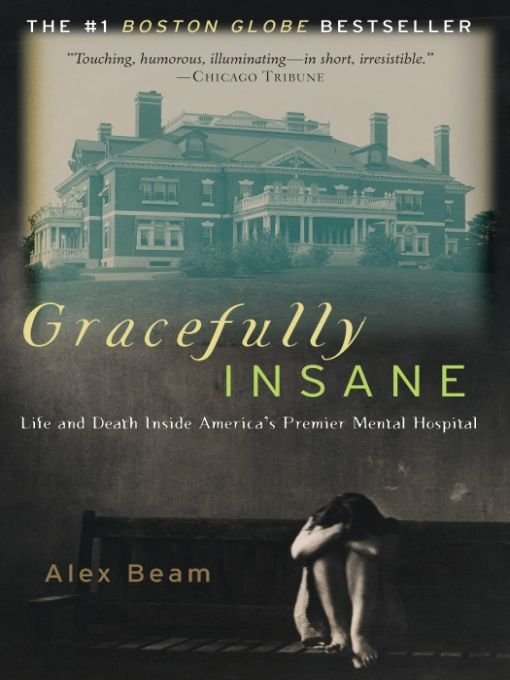

Gracefully Insane

Authors: Alex Beam

Table of Contents

PRAISE FOR

Gracefully Insane

:

Gracefully Insane

:

“[Beam] elicits fascinating stories from both residents and staff ... [and] ... has nicely traced the history of this institution and its inhabitants.”

Entertainment Weekly

“Beam tells good stories and with an appropriate tone—intrigued and respectful, but not pious.”

Washington Post

“A brilliant blend of substance, story, and commentary,

Gracefully Insane

is at once an academic exploration of an institution and an insightful glimpse inside troubled lives.”

Gracefully Insane

is at once an academic exploration of an institution and an insightful glimpse inside troubled lives.”

Boston Magazine

“A lucid, compelling social and cultural history of a segment of American life that is worthy of both James brothers: Henry’s storytelling gifts and his discerning eye for class and its psychological consequences, and William’s knowing medical awareness.... A major narrative achievement.”

Robert Coles

“[A] fascinating, gossipy social history ... More than a history of a psychiatric institution, the book offers an unusual glimpse of a celebrated American estate: the Boston aristocracy ...”

Publishers Weekly

“An engaging history of the psychiatric treatment of the American socioeconomic elite since the early 19th century.”

Barron’s Financial Review

“Alex Beam packs the whole history of psychiatry into the biography of a single institution that for nearly 200 years has offered refuge to some of America’s most talented thinkers and artists.... A gracious, gossipy, well-informed, page-turner of a book, a pleasure to read.”

Diane Middlebrook

“An admirable institutional history, and more so, a captivating social history, for what makes McLean distinctive, its style and sensibility, is part and parcel of what Boston, as a cultural instance, represents.”

Kirkus Reviews

“Often fascinating ..., the book weaves together the compelling history of McLean and those who came seeking its refuge.”

Book Magazine

“Combines the history of McLean Hospital with reflections on the history of psychiatry. The result is a wonderful book for psychologists, psychiatrists, and history buffs—and for anyone interested in mental health.”

Steven Pinker

“An oddly entertaining narrative that reads easily and supplies fascinating details about business, pop music, and literary figures.”

Library Journal

ALSO BY ALEX BEAM

Fellow Travelers

The Americans Are Coming!

The Americans Are Coming!

To my mother and father

... (This is the house for the “mentally ill.”)

What use is my sense of humor?

I grin at Stanley, now sunk in his sixties,

once a Harvard all-American fullback

(if such were possible!)

still hoarding the build of a boy in his twenties,

as he soaks, a ramrod

with the muscle of a seal

in his long tub,

vaguely urinous from the Victorian plumbing,

A kingly granite profile in a crimson golf-cap,

worn all day, all night,

he thinks only of his figure

of slimming on sherbet and ginger ale—

more cut off from words than a seal.

I grin at Stanley, now sunk in his sixties,

once a Harvard all-American fullback

(if such were possible!)

still hoarding the build of a boy in his twenties,

as he soaks, a ramrod

with the muscle of a seal

in his long tub,

vaguely urinous from the Victorian plumbing,

A kingly granite profile in a crimson golf-cap,

worn all day, all night,

he thinks only of his figure

of slimming on sherbet and ginger ale—

more cut off from words than a seal.

This is the way day breaks in Bowditch Hall at McLean’s;

the hooded night lights bring out “Bobbie,”

Porcellian ’29

a replica of Louis XVI

without the wig—

redolent and roly-poly as a sperm whale,

as he swashbuckles about in his birthday suit

and horses at chairs.

the hooded night lights bring out “Bobbie,”

Porcellian ’29

a replica of Louis XVI

without the wig—

redolent and roly-poly as a sperm whale,

as he swashbuckles about in his birthday suit

and horses at chairs.

These victorious figures of bravado ossified young.

In between the limits of day,

hours and hours go by under the crew haircuts

and slightly too little nonsensical bachelor twinkle

of the Roman Catholic attendants.

(There are no Mayflower

screwballs in the Catholic Church.)

In between the limits of day,

hours and hours go by under the crew haircuts

and slightly too little nonsensical bachelor twinkle

of the Roman Catholic attendants.

(There are no Mayflower

screwballs in the Catholic Church.)

After a hearty New England breakfast,

I weigh two hundred pounds

this morning. Cock of the walk,

I strut in my turtle-necked French sailor’s jersey

before the metal shaving mirrors,

and see the shaky future grow familiar

in the pinched, indigenous faces

of these thoroughbred mental cases,

twice my age and half my weight.

We are all old-timers,

each of us holds a locked razor.

I weigh two hundred pounds

this morning. Cock of the walk,

I strut in my turtle-necked French sailor’s jersey

before the metal shaving mirrors,

and see the shaky future grow familiar

in the pinched, indigenous faces

of these thoroughbred mental cases,

twice my age and half my weight.

We are all old-timers,

each of us holds a locked razor.

from “Waking in the Blue,” by Robert Lowell

1

A Visit to the Museum of the Cures

E

veryone makes the same comment: It doesn’t look like a mental

hospital. The carefully landscaped grounds, dotted with four- and five-story Tudor mansions and red brick dormitories, could belong to a prosperous New England prep school or perhaps a small, well-endowed college tucked away in the Boston suburbs. There are no fences, no guards, no locked gates. Over time, of course, you see the signs. Iron grilles surround the staircases inside the few remaining locked wards. On some halls, the nurses’ stations are enclosed in thick Plexiglas. The washroom mirrors are polished metal, not glass. But on first acquaintance, the only indication that you have entered one of America’s oldest and most prestigious mental hospitals is a large sign jutting into Mill Street: McLean Hospital.

veryone makes the same comment: It doesn’t look like a mental

hospital. The carefully landscaped grounds, dotted with four- and five-story Tudor mansions and red brick dormitories, could belong to a prosperous New England prep school or perhaps a small, well-endowed college tucked away in the Boston suburbs. There are no fences, no guards, no locked gates. Over time, of course, you see the signs. Iron grilles surround the staircases inside the few remaining locked wards. On some halls, the nurses’ stations are enclosed in thick Plexiglas. The washroom mirrors are polished metal, not glass. But on first acquaintance, the only indication that you have entered one of America’s oldest and most prestigious mental hospitals is a large sign jutting into Mill Street: McLean Hospital.

Although I had already interviewed several doctors in their offices, I took my first formal tour of the campus on a sunny, earlysummer

Saturday in 1998. McLean was hosting an orientation meeting for its neighbors in the well-to-do town of Belmont, Massachusetts. Our group of twenty could just as well have been bird watchers out for a jaunt. In fact, as we strode along the sculptured walkways cut through the scrubby New England forest, several men and women revealed themselves to be Audubon Society members, who instantly recognized the hospital’s dense stands of oak and elm forests as nesting grounds for red-tailed hawk and horned and screech owls. There were two “soccer moms” in our group, real soccer moms, it turns out—they

played

soccer. Everyone was wearing sensible clothing for our tour of what was once America’s premier insane asylum.

Saturday in 1998. McLean was hosting an orientation meeting for its neighbors in the well-to-do town of Belmont, Massachusetts. Our group of twenty could just as well have been bird watchers out for a jaunt. In fact, as we strode along the sculptured walkways cut through the scrubby New England forest, several men and women revealed themselves to be Audubon Society members, who instantly recognized the hospital’s dense stands of oak and elm forests as nesting grounds for red-tailed hawk and horned and screech owls. There were two “soccer moms” in our group, real soccer moms, it turns out—they

played

soccer. Everyone was wearing sensible clothing for our tour of what was once America’s premier insane asylum.

McLean was showing off its 240-acre campus to promote its new Hospital Re-Use Master Plan. Starting in the 1980s, neither private insurers nor government programs like Medicare and Medicaid were willing to finance the lengthy stays and staff-intensive therapy that had been McLean’s specialty for almost two centuries. Whereas once well-heeled patients had checked in for months’ if not years’ worth of expensive, residential therapy, the standard admission was now the “five-day”: time enough for a quick psychiatric diagnosis, stabilization on drugs, and release “into the community,” meaning to a halfway house or, in the most hopeful scenario, back to one’s family. By the early 1990s, McLean was losing millions of dollars a year. It came within a hair’s breadth of being closed down. The hospital was foundering like a luxury ocean liner competing in the age of jet travel.

To save McLean, the businessmen who sat on the board of trustees opted to “restructure” the hospital. McLean had already shrunk dramatically; in the late 1990s, staffers were preparing just 100 beds a night, compared with 340 during most of the twentieth century. Entire buildings had already been closed. “It occurred to us that we had about 250 acres and 800,000 square feet of building space, and given the profile of the way we were delivering the medicine, we probably needed only 50 acres and 300,000 square feet,” Charles Baker, a former chairman of the board, explained to

me. The eventual Master Plan called for selling off about half the asylum’s acreage and keeping an inner core of fifty acres for patient treatment and research labs. The rest would be given to the town as public open space. The idea was to raise $40 million, erase the hospital’s outstanding debt, and rescue McLean.

me. The eventual Master Plan called for selling off about half the asylum’s acreage and keeping an inner core of fifty acres for patient treatment and research labs. The rest would be given to the town as public open space. The idea was to raise $40 million, erase the hospital’s outstanding debt, and rescue McLean.

The tours eventually had the desired impact; after years of town-gown bickering, Belmont finally voted to allow McLean to de-accession its real estate treasures in 1999. McLean had signed a deal to turn twelve acres of scrub forest on its southern perimeter into a mirror-windowed, 300,000-square-foot biomedical research park of the kind to be seen on the outskirts of Princeton, Atlanta, Seattle, or pretty much any white-collar, city-suburb in America. Twenty-six acres along busy Mill Street will be developed for town houses, to be priced between $600,000 and $650,000. At a separate briefing, an official of the Northland Development Corporation showed us how the new homes would be painted in earth colors, surrounded by trees, and kept low to the ground so as not to change the profile of the west-facing wooded hill. He briefly addressed the potential challenge of selling expensive homes abutting the grounds of an insane asylum, but he hoped it would not be a problem.

Down the hill from the town houses, McLean has convinced the American Retirement Corporation to build a 352-unit “eldercare center,” an upscale retirement home. Other plots have been earmarked to placate various constituencies that hold McLean’s fate in their hands. The 130 acres of open space, some of it abutting an Audubon Society sanctuary, should quiet Belmont’s vocal environmentalists. The hospital will donate one and a half acres to expand—and silence—a neighboring housing development for the elderly. A private school on the hospital’s northern border will get land for a new soccer field. And the town fathers of Belmont will be rewarded with twenty acres for their long-standing pet project, a cemetery expansion.

Throughout the process, McLean, a teaching hospital of Harvard University, has behaved with perfect decorum. I attended a

citizens’ meeting where an abutter who opposed the Master Plan objected to the “quick fix” cemetery expansion, which, he complained, would serve Belmont’s needs for only the next seventy-five years. A development staffer working with the hospital replied, “We’ll show you a picture of a forest cemetery in Sweden,” invoking the Scandinavian penchant for tasteful, appropriately scaled development, even for cemeteries. At a Belmont Conservation Commission meeting, a small group of environmentalists demanded special consideration for a tiny brook flowing down the southern slope of the site of the proposed office park development, a stream that eventually reaches the Mystic River. The McLean lawyers huddled briefly and then agreed not to disturb any land within one hundred feet of the running water.

citizens’ meeting where an abutter who opposed the Master Plan objected to the “quick fix” cemetery expansion, which, he complained, would serve Belmont’s needs for only the next seventy-five years. A development staffer working with the hospital replied, “We’ll show you a picture of a forest cemetery in Sweden,” invoking the Scandinavian penchant for tasteful, appropriately scaled development, even for cemeteries. At a Belmont Conservation Commission meeting, a small group of environmentalists demanded special consideration for a tiny brook flowing down the southern slope of the site of the proposed office park development, a stream that eventually reaches the Mystic River. The McLean lawyers huddled briefly and then agreed not to disturb any land within one hundred feet of the running water.

Other books

Spinning Around by Catherine Jinks

Her Billionaire Secret Part 3: An Alpha Billionaire Romance by Jenna Chase, Elise Kelby

Dirty Rotten Tendrils by Collins, Kate

Without Words by Ellen O'Connell

314 Book 2 by Wise, A.R.

The Fallen Queen by Emily Purdy

Chill Factor by Chris Rogers

Murder With Puffins by Donna Andrews

Braking for Bodies by Duffy Brown