God's Battalions (13 page)

Authors: Rodney Stark,David Drummond

At that point the Turks might have settled down to life as a ruling elite over a substantial and wealthy territory, but for religious antagonism. The Turks were orthodox Sunni Muslims, but the Fatimid Caliphate in Cairo was ruled by Shiites—heretics “guilty” of splitting Islam. So the Turks moved west and south, invading Fatimid territory, including the Holy Land.

The Turkish commander was Atsiz bin Uwaq, who had served in Alp Arslan’s court until he deserted to serve the Fatimids in Palestine, whereupon he deserted the Fatimids and in 1071 became commander of the Turkish invasion forces. Historians debate

61

whether Atsiz took Jerusalem in 1071 during the first year of his campaign, or in 1073, but it is agreed that Acre was taken in 1074 and Damascus in 1075. At that point Atsiz turned south, intent on driving the Fatimids from Egypt, but he was badly defeated in 1077. In the wake of the Fatimid victory over the Turks, there were risings by Fatimid Muslims in Palestine, and Atsiz was forced to flee all the way to Damascus. But he soon returned and laid siege to Jerusalem. Given Atsiz’s promise of safety, the city opened its gates, whereupon the Turkish troops were released to slaughter and pillage, and thousands died. Next, Atsiz’s troops murdered the populations of Ramla and Gaza, then Tyre and Jaffa.

62

In the midst of all this turmoil and bloodshed, it cannot have been a good time to be a Christian pilgrim. And it soon got worse. Not only because the Turkish rulers persecuted pilgrims, but because they did not (possibly they could not) interfere with the hordes of bandits and local village officials who preyed upon them. A few large, well-armed groups got through, such as the one led by Robert I of Flanders in 1089. But most either were victimized or decided to turn back.

63

Even the twelfth-century Syrian historian al-‘Azimi acknowledged that in 1093 Muslims in Palestine prevented Christian pilgrims from going to Jerusalem. He also suggested that the survivors’ going home and spreading the word caused the Crusades to be organized. Moshe Gil pointed out that by speaking of survivors, al-‘Azimi clearly suggested “that there had been a massacre,”

64

and perhaps many of them.

Finally, the nobility of Europe were not dependent on the pope or on Alexius Comnenus for information on the brutalization of Christian pilgrims. They had trustworthy, independent information from their own relatives and friends who had managed to survive and who had returned “to the West weary and impoverished, with a dreadful tale to tell”

65

—the very people mentioned by al-‘Azimi.

CONCLUSION

The Crusades were not unprovoked. Muslim efforts at conquest and colonization still continued in the eleventh century (and for centuries to come). Pilgrims did risk their lives to go to the Holy Land. The sacred sites of Christianity were not secure. And the knights of Christendom were confident that they could put things right.

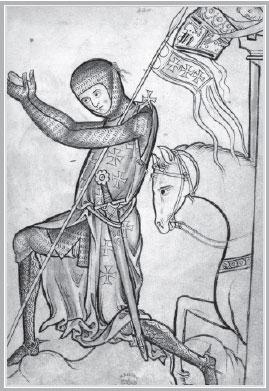

A knight kneels in prayer as he prepares to set off on the First Crusade. At the top right, his servant leans over the turret with his master’s helmet.

©

British Library / HIP / Art Resource, NY

I

T WAS ONE THING

for Pope Urban II to conclude that Europe should rally in support of Eastern Christianity and the liberation of the Holy Land. But how was he able to bring it about? How were tens of thousands of people convinced to commit their lives and fortunes to such a challenge? Many of them, especially those recruited by Peter the Hermit, may have been unaware of what really lay ahead. But the great nobles and knights were neither foolish nor naive. They knew much about the journey itself: some had already been to the Holy Land on a pilgrimage, and all of them had close relatives and associates who had been there. So they knew they faced a very long and perilous journey at the end of which there would be many bloody battles against a dangerous and determined foe. They also were fully aware that there was no pot of gold awaiting them in the sands of Palestine. So, how were they recruited?

PREACHING THE CRUSADES

No matter how eloquent Pope Urban II was when addressing the crowd at Clermont, one speech could not have launched thousands of knights to the Holy Land. Indeed, by the time he reached Clermont the pope had been on the road for four months visiting important Frankish (French) nobles, abbots, and bishops. Since most of them subsequently played leading roles in mounting the First Crusade, we can be sure that the pope used his visits to enlist their support. If we credit the story that during his famous speech at Clermont some in the audience began to cut out crosses and sew them onto their chests, we can assume they had prepared to do this in advance: knights did not usually carry sewing kits. Moreover, according to one account, when the pope had finished speaking “envoys from Raymond, count of Toulouse, appeared and announced that their lord had taken the cross.”

1

But whatever the pope had done ahead of time to line up support, Clermont was still only the beginning; the plan had yet to be widely “sold” before it could happen. Consequently, according to the account by Baldric, archbishop of Dol, at the end of his speech at Clermont, Urban turned to the bishops and said, “You, brothers and fellow bishops; you fellow priests and sharers with us in Christ, make this same announcement through the churches committed to you, and with your whole soul vigorously preach the journey to Jerusalem.”

2

But even had they all done so, their efforts probably would have been insufficient. The First Crusade became a reality only because the pope was able to recruit hundreds to preach it who had not been at Clermont. To understand how he achieved this, it will be helpful to see just what kind of a pope he was and the churchly resources available to him.

Two Churches

In many ways, the conversion of Constantine was a catastrophe for Christianity. It would have been enough had he merely given Christianity the legal right to exist without persecution. But when he made Christianity “the most favoured recipient of the near-limitless resources of imperial favour,”

3

he undercut the authentic commitment of the clergy. Suddenly, a faith that had been meeting in homes and humble structures was housed in magnificent public buildings; the new church of Saint Peter built by Constantine in Rome was modeled on the basilican form used for imperial throne halls. A clergy recruited from the people and modestly sustained by member contributions suddenly gained immense power, status, and wealth as part of the imperial civil service. Bishops “now became grandees on a par with the wealthiest senators.”

4

Consequently, in the words of Richard Fletcher, the “privileges and exemptions granted the Christian clergy precipitated a stampede into the priesthood.”

5

As Christian offices became another form of imperial preferment, they were soon filled by the sons of the aristocracy. There no longer was an obligation that one be morally qualified, let alone that one be “called.” Gaining a church position was mainly a matter of influence, of commerce, and eventually of heredity. Simony became rife: an extensive and very expensive traffic in religious offices developed, involving the sale not only of high offices such as bishoprics, but even of lowly parish placements. There soon arose great clerical families, whose sons followed their fathers, uncles, and grandfathers into holy office, including the papacy.

6

As a result, many dissolute, corrupt, lax, and insincere people gained high positions: Pope Benedict IX (1012–1055), the nephew of two previous popes, took office without even having been ordained as a priest and caused so many scandals by “whoring his way around Rome” that he was bribed to leave office.

7

Of course, many who entered the religious life were not careerists or libertines; even some sons and daughters of the clerical families were deeply sincere. Consequently, there arose what became, in effect, two parallel churches. These can usefully be identified as the

Church of Power

and the

Church of Piety.

The Church of Power was the main body of the Church as it evolved in response to the immense power and wealth bestowed on the clergy by Constantine. It included the great majority of priests, bishops, cardinals, and popes who ruled the Church most of the time until the Counter-Reformation set in during the sixteenth century. In many ways the Church of Piety was sustained as a reaction against the Church of Power. It might have been silenced or at least shunted aside but for the fact that it had an unyielding base in monasticism, which, in turn, had very strong support among the ruling elites: 75 percent of ascetic medieval saints were sons and daughters of the nobility, including many sons and daughters of kings.

8

Remarkably, at the same time that there had begun a “stampede” into the priesthood by the sons of privilege, there was a rapid expansion of monasticism: by the middle of the fourth century there were many thousands of monks and nuns, nearly all of them living in organized communities. Naturally, those living an ascetic life felt themselves spiritually superior to the others, as was in fact acknowledged by Catholic theology. However, their antagonism toward the regular clergy and, especially, the Church hierarchy had a different basis; it was not merely that these men were not leading ascetic lives, but that so many were leading dissolute lives. This was an issue that would not subside. Again and again leaders of the Church of Piety attempted to reform the Church of Power, and during several notable periods they managed to gain control of the papacy and impose major changes. It was during one of these interludes of control by the Church of Piety that Urban II rose to the Chair of Peter.

Otho (or Odo) of Lagery was born into the northern French nobility in 1042. During his early teens he entered the Church and quickly rose to be archdeacon of the cathedral at Rheims. In 1067 he entered the monastery of Cluny, which had rapidly become the largest and most aggressive of Europe’s monastic organizations. Here Otho soon gained the office of grand prior, second only to the abbot, and in 1078 Pope Gregory VII (himself a former monk and an ardent member of the Church of Piety) appointed him cardinal-bishop of Ostia. He was elected pope by acclamation in 1088 and took the name Urban II. He died on July 29, 1099, two weeks after the crusaders had taken Jerusalem but before word of their victory had reached the West.

That Urban II was an esteemed member of the Church of Piety was important because it gave him credibility with the friars and monks who did most of what little preaching was done in medieval Europe; “preaching to the laity was, at best, sporadic”

9

in this era. Local parish priests did very little preaching. It was not required that they do so during Mass, and in any event, Mass attendance was extremely low.

10

What effective preaching took place was done by monks and wandering friars, usually in the marketplace rather than in a church, and it was they who accepted the pope’s request to preach support for the First Crusade. Hence, hundreds (perhaps thousands) of friars and monks spread the pope’s message in every hamlet, village, and town. Among them were three very distinguished men who had turned away from very successful church careers to live as ascetics in the forest of Craon: Robert of Arbissel, Vitalis of Mortain, and Bernard of Tiron. At the invitation of the pope, each emerged from seclusion to preach the First Crusade, and subsequently each successfully founded a new monastic order.

And just as these three men, like the pope himself, were from upper-class backgrounds, the same was true of most monks, which enabled them to witness for the Crusade directly to their noble relatives. In this era, monks usually entered their orders through the process of

oblation

(or offering), wherein a young boy (far less often a girl) was enrolled in a religious order by parents who paid a substantial entry fee. Too often this practice has incorrectly been interpreted as a method for disposing of “excess” sons who did not stand to inherit.

11

In fact, the entry fee usually was equal to a quite substantial inheritance.

12

In any event, oblation was such a common practice that most of the nobility had uncles, sons, brothers, and nephews living nearby in religious cloisters with whom they usually remained in close touch. This arrangement sustained strong ties between the Church of Piety and the nobility and had very significant effects on the religiousness of the privileged families.

However, the pope did not simply delegate the task of preaching the Crusade. From Clermont he took to the road once more, spending the next nine months traveling more than two thousand miles through France, “entering country towns, the citizens of which had never seen a king or anyone of such international importance…accompanied by a flock of cardinals, archbishops, and bishops…whose train must have stretched across miles of countryside.”

13

Everywhere he went, the pope consecrated local chapels, churches, cathedrals, monasteries, convents, and cemeteries and blessed local altars and relics. Most of these occasions were public ceremonies, and huge crowds turned out—or at least “huge” in terms of the size of the local population (the population of Paris was about twenty-five thousand).

14

The pope used all these opportunities to preach the Crusade. Perhaps even more important, the pope’s visit and his preaching stimulated many locals, including bishops, to continue preaching the Crusade long after the pope and his party had departed.

15

Moreover, while the pope “toured France, papal letters and legates travelled swiftly to England, Normandy, and Flanders, to Genoa and Bologna, exhorting, commanding and persuading…Later in the same year the pope sent the bishops of Orange and Grenoble to preach the crusade in Genoa, and bring the formidable Genoese sea-power into the war.”

16

In many ways, those preaching the Crusade were too successful. They convinced not only thousands of fighting men to volunteer, but also even larger numbers of men and women with no military potential. Soon thousands of these people, many of them peasants, traveled east under the leadership of Peter the Hermit, doing a great deal of harm along the way, and then suffered pointless deaths—as will be seen.

Penitential Warfare

Many skeptics have noted that the pilgrimages often failed to improve the subsequent behavior of pilgrims. The main issue here is not that some pilgrims were like Fulk III, who returned from each of his four pilgrimages ready and eager to sin again. The issue seems to be the expectation that an authentic pilgrimage ought to have fundamentally transformed a pilgrim’s character and personality—or at least to have changed an individual into a far more peaceful and forgiving sort of person. But that was not a typical outcome. Instead, most of the fighting men who went on a pilgrimage returned as fierce and ready to do battle as before. For example, according to the

Chronicle of Monte Cassino

(c. 1050s), “[F]orty Normans dressed as pilgrims, on their return from Jerusalem, disembarked at Salerno. These were men of considerable bearing, impressive-looking, men of the greatest experience in warfare. They found the city besieged by Saracens. Their souls were inflamed with a call to God. They demanded arms and horses from Gaimare the prince of Salerno, got them, and threw themselves ferociously upon the enemy. They killed and captured many and put the rest to flight, achieving a miraculous victory with the help of God. They swore they had done all this only for the love of God and of the Christian faith; they refused reward and refused to remain in Salerno.”

17

That even very pious knights found pacifism incomprehensible may puzzle some having modern sensibilities, but that assumption was fundamental to Pope Urban’s call for a Crusade. Having come from a family of noble knights, the pope took their propensity for violence for granted. He fully understood that from early childhood a knight was raised to regard fighting as his chief function and that throughout “his life the knight spent most of his time in practicing with his arms or actually fighting. Dull periods of peace were largely devoted to hunting on horseback such savage animals as the wild boar.”

18

Since the pope could not get the knights of Europe to observe a peace of God, at least he could enlist them to serve in God’s battalions and to direct their fierce bravery toward a sacred cause. And to bring this about, Urban proposed something entirely new—that participation in the Crusade was the moral equivalent of serving in a monastic order, in that special holiness and certainty of salvation would be gained by those who took part.

As Guibert of Nogent recalled Urban’s words at Clermont: “God has instituted in our time holy wars, so that the order of knights…[who] have been slaughtering one another…might find a new way of gaining salvation. And so they are not forced to abandon secular affairs completely by choosing the monastic life or any religious profession, as used to be the custom, but can attain some measure of God’s grace while pursuing their own careers, with the liberty and dress to which they are accustomed.”

19

In this way Urban took a realistic view not only of the knighthood, but also of the military situation. Tens of thousands of dedicated pacifists could do nothing to liberate the Holy Land. It was going to take an army of belligerent knights who were motivated but not transformed by the promise of salvation. Thus, the invention of penitential warfare.