Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (77 page)

Read Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid Online

Authors: Douglas R. Hofstadter

Tags: #Computers, #Art, #Classical, #Symmetry, #Bach; Johann Sebastian, #Individual Artists, #Science, #Science & Technology, #Philosophy, #General, #Metamathematics, #Intelligence (AI) & Semantics, #G'odel; Kurt, #Music, #Logic, #Biography & Autobiography, #Mathematics, #Genres & Styles, #Artificial Intelligence, #Escher; M. C

Achilles: We can just step inside right here. Follow me.

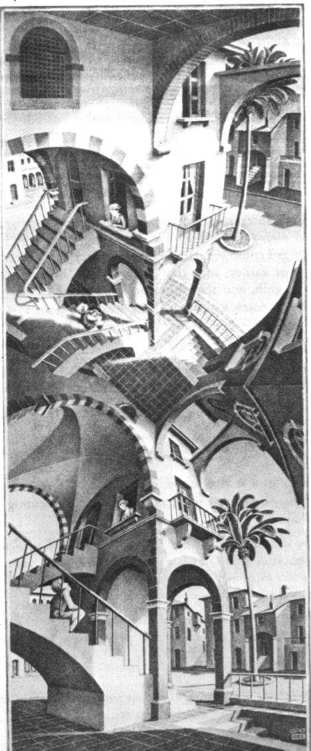

FIGURE 74. Above and Below,

by M.C. Escher (lithograph 1947

).

(Achilles opens the door. They enter, and begin climbing the steep helical staircase

inside the tower.)

Tortoise (

puffing slightly

): I'm a little out of shape for this sort of exercise, Achilles. How much further do we have to go?

Achilles: Another few flights ... but I have an idea. Instead of walking on the top side of these stairs, why don't you walk on the underside?

Tortoise: How do I do THAT?

Achilles: Just hold on tightly, and climb around underneath-there's room enough for you.

You'll find that the steps make just as much sense from below as from above ...

Tortoise (

gingerly shifting himself about

): Am I doing it right?

Achilles: You've got it!

Tortoise (

his voice slightly muffled

): Say-this little maneuver has got me confused.

Should I head upstairs or downstairs, now?

Achilles: Just continue heading in the same direction as you were before. On your side of the staircase, that means go

DOWN

, on mine it means

UP

.

Tortoise: Now you're not going to tell me that I can get to the top of the tower by going down, are you?

Achilles: I don't know, but it works ...

(And so they begin spiraling in synchrony, with A always on one side, and T

matching him on the other side. Soon they reach the end of the staircase.)

Now just undo the maneuver, Mr. T. Here-let me help you up.

(He lends an arm to the Tortoise, and hoists him back to the other side of the

stairs.)

Tortoise: Thanks. It was a little easier getting back up.

(And they step out onto the roof, overlooking the town.)

That's a lovely view, Achilles. I'm glad you brought me up here-or rather,

DOWN

here.

Achilles: I figured you'd enjoy it.

Tortoise: I've been thinking about that obscene phone call. I think I understand it a little better now.

Achilles: You do? Would you tell me about it?

Tortoise: Gladly. Do you perchance feel, as I do, that that phrase "preceded by its quotation" has a slightly haunting quality about it?

Achilles: Slightly, yes-extremely slightly.

Tortoise: Can you imagine something preceded by its quotation?

Achilles: I guess I can conjure up an image of Chairman Mao walking into a banquet room in which there already hangs a large banner with some of his own writing on it.

Here would be Chairman Mao, preceded by his quotation.

Tortoise: A most imaginative example. But suppose we restrict the word

"preceded" to the idea of precedence on a printed sheet, rather than elaborate entries into a banquet room.

Achilles: All right. But what exactly do you mean by "quotation" here? Tortoise: When you discuss a word or a phrase, you conventionally put it in quotes. For example, I can say,

The word "philosopher" has five letters.

Here, I put "philosopher" in quotes to show that I am speaking about the WORD

"philosopher" rather than about a philosopher in the flesh. This is called the USEMENTION distinction.

Achilles: Oh?

Tortoise: Let me explain. Suppose I were to say to you,

Philosophers make lots of money.

Here, I would be USING the word to manufacture an image in your mind of a twinkle-eyed sage with bulging moneybags. But when I put this word-or any word-in quotes, I subtract out its meaning and connotations, and am left only with some marks on paper, or some sounds. That is called "MENTION". Nothing about the word matters, other than its typographical aspects-any meaning it might have is ignored.

Achilles: It reminds me of using a violin as a fly swatter. Or should I say mentioning"?

Nothing about the violin matters, other than its solidity-any meaning or function it might have is being ignored. Come to think of it, I guess the fly is being treated that way, too.

Tortoise: Those are sensible, if slightly unorthodox, extensions of the use-mention distinction. But now, I want you to think about preceding something by its own quotation.

Achilles: All right. Would this be correct?

"HUBBA" HUBBA

Tortoise: Good. Try another.

Achilles: All right.

"'PLOP' IS NOT THE TITLE OF ANY BOOK. SO FAR AS I KNOW"'

'PLOP' IS NOT THE TITLE OF ANY BOOK, SO FAR AS I KNOW.

Tortoise: Now this example can be modified into quite an interesting specimen, simply by dropping `Plop'. Achilles: Really? Let me see what you mean. It becomes

"IS NOT THE TITLE OF ANY BOOK, SO FAR AS I KNOW"

IS NOT THE TITLE OF ANY BOOK, SO FAR AS I KNOW.

Tortoise: You see, you have made a sentence.

Achilles: So I have. It is a sentence about the pjrase “is not the toitle of any book, as far as I know”, and quite a silly one too.

Tortoise: Why silly?

Achilles: Because it's so pointless. Here's another one for you:

“WILL BE BOYS" WILL BE BOYS.

Now what does that mean? Honestly, what a silly game.

Tortoise: Not to my mind. It's very earnest stuff, in my opinion. In fact this operation of preceding some phrase by its quotation is so overwhelmingly important that I think I'll give it a name.

Achilles: You will? What name will you dignify that silly operation by?

Tortoise: I believe I'll call it "to quine a phrase", to quine a phrase.

Achilles: "Quine"? What sort of word is that?

Tortoise: A five-letter word, if I'm not in error.

Achilles: What 1 was driving at is why you picked those exact five letters in that exact order.

Tortoise: Oh, now I understand what you meant when you asked me "What sort of word is that?" The answer is that a philosopher by the name of "Willard Van Orman Quine"

invented the operation, so I name it in his honor. However, I cannot go any further than this in my explanation. Why these particular five letters make up his name-not to mention why they occur in this particular order-is a question to which I have no ready answer. However, I'd be perfectly willing to go and

Achilles: . Please don't bother! I didn't really want to know everything about Quine's name. Anyway, now I know how to quine a phrase. It's quite amusing. Here's a quined phrase:

”IS A SENTENCE FRAGMENT" IS A SENTENCE FRAGMENT.

It's silly but all the same I enjoy it. You take a sentence fragment, quine it, and lo and behold, you've made a sentence! A true sentence, in this case.

Tortoise: How about quining the phrase "is a king with without no subject”?

Achilles: A king without a subject would be---

Tortoise: -an anomaly, of course. Don't wander from the point. Let's have quines first, and kings afterwards!

Achilles: I'm to quine that phrase, am I? All right

"IS A KING WITH NO SUBJECT" IS A KING WITH NO SUBJECT.

It seems to me that it might make more sense if it said "sentence" instead of "king".

Oh, well. Give me another!

Tortoise: All right just one more. Try this one:

"WHEN QUINED, YIELDS A TORTOISE'S LOVE SONG"

Achilles: That should be easy ... I'd say the quining gives this:

"WHEN QUINED, YIELDS A TORTOISE'S LOVE SONG"

WHEN QUINED, YIELDS A TORTOISE'S LOVE SONG

Hmmm… Thereś something just a little peculiar here. Oh, I see what it is! The sentence is talking about itself! Do you see that?

Tortoise: What do you mean? Sentences can't talk.

Achilles: No, but they

REFER

to things-and this one refers directly unambiguously-unmistakably-to the very sentence which it is! You just have to think back and remember what quining is all about.

Tortoise: I don't see it saying anything about itself. Where does it say "me", or: "this sentence", or the like?

Achilles: Oh, you are being deliberately thick-skulled. The beauty of it lies in just that: it talks about itself without having to come right out and say so!

Tortoise: Well, as I'm such a simple fellow, could you just spell it all out for me, Achilles: Oh, he is such a Doubting Tortoise ... All right, let me see ... Suppose I make up a sentence-I'll call it "Sentence P"-with a blank in it.

Tortoise: Such as?

Achilles: Such as ...

“________WHEN QUINED, YIELDS A TORTOISE'S LOVE SONG".

Now the subject matter of Sentence P depends on how you fill in the blank. But once you've chosen how to fill in the blank, then the subject matter is determined: it is the phrase which you get by QUINING the blank. Call that "Sentence Q", since it is produced by an act of quining.

Tortoise: That makes sense. If the blank phrase were "is written on old jars of mustard to keep them fresh", then Sentence Q would have to be

"IS WRITTEN ON OLD JARS OF MUSTARD TO KEEP THEM FRESH"

IS WRITTEN ON OLD JARS OF MUSTARD TO KEEP THEM FRESH.

Achilles: True, and Sentence P makes the claim (though whether it is valid or not, I do not know) that Sentence Q is a Tortoise's love song. In any case, Sentence P here is not talking about itself, but rather about Sentence Q. Can we agree on that much?

Tortoise: By all means, let us agree-and what a beautiful song it is, too.

Achilles: But now I want to make a different choice for the blank, namely

: "WHEN QUINED, YIELDS A TORTOISE'S LOVE SONG".

Tortoise: Oh, heavens, you're getting a little involved here. I hope this all isn't going to be too highbrow for my modest mind.

Achilles: Oh, don't worry-you'll surely catch on. With this choice, Sentence Q

becomes .. .

"WHEN QUINED, YIELDS A TORTOISE'S LOVE-SONG"

WHEN QUINED, YIELDS A TORTOISE'S LOVE-SONG.

Tortoise: Oh, you wily old warrior you, I catch on. Now Sentence Q is just the same as Sentence P.

Achilles: And since Sentence Q is always the topic of Sentence P, there is a loop now, P points back to itself. But you see, the self-reference is a

sort of accident. Usually Sentences Q and P are entirely unlike each other; but with the right choice for the blank in Sentence-P, quining will do this magic trick for you.

Tortoise: Oh, how clever. I wonder why I never thought of that myself. Now tell me: is the following sentence self-referential?

"IS COMPOSED OF FIVE WORDS" IS COMPOSED OF FIVE WORDS.

Achilles: Hmm ... I can't quite tell. The sentence which you just gave is not really about itself, but rather about the phrase "is composed of five words". Though, of course, that phrase is PART of the sentence ...

Tortoise: So the sentence refers to some part of itself-so what? Achilles: Well, wouldn't that qualify as self-reference, too?

Tortoise: In my opinion, that is still a far cry from true-self-reference. But don't worry too much about these tricky matters. You'll have ample time to think about them in the future. Achilles: I will?

Tortoise: Indeed you will. But for now, why don't you try quining the phrase "yields falsehood when preceded by its quotation"?

Achilles: I see what you're getting at-that old obscene phone call. Quining it produces the following:

"YIELDS FALSEHOOD WHEN PRECEDED BY ITS QUOTATION"

YIELDS FALSEHOOD WHEN PRECEDED BY ITS QUOTATION.

So this is what that caller was saying! I just couldn't make out where the quotation marks were as he spoke. That certainly is an obscene remark! People ought to be jailed for saying things like that!

Tortoise: Why in the world?

Achilles: It just makes me very uneasy. Unlike the earlier examples, I can't quite make out if it is a truth or a falsehood. And the more I think about it, the more I can't unravel it. It makes my head spin. I wonder what kind of a lunatic mind would make something like that up, and torment innocent people in the night with it?

Tortoise: I wonder ... Well, shall we go downstairs now?

Achilles: We needn't go down-we're at ground level already. Let's go back inside-you'll see. (

They go into the tower, and come to a small wooden door

.) We can just step outside right here. Follow me.

Tortoise: Are you sure? I don't want to fall three floors and break my shell.

Achilles: Would I fool you?

(And he opens the door. In front of them sits, to all appearances, the same boy,

talking to the same young woman. Achilles and Mr. T walk up what seem to be the

same stairs they walked down to enter the tower, and find themselves in what looks

like

just

the

same

courtyard

they

first