Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (28 page)

Read Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right Online

Authors: Jennifer Burns

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #Philosophy, #Movements

Nathan completed his master’s degree and began working as a full-time therapist. Frank underwent the most dramatic transformation. One evening, spurred by a philosophical disagreement, several members of the Collective tried painting. The results quickly disproved Rand’s assertion that artistic skills could be easily taught to anyone, for Frank outstripped the others immediately. As his background in floral design suggested, Frank was a natural. Soon he was drawing at every turn, filling sketchbooks with his work.

Rand too was rejuvenated and relieved. She was finally prepared to begin shopping the manuscript around, and with

The Fountainhead

still selling briskly, had her pick of eager publishers. Bobbs-Merrill, which had first right of refusal on her next book, pronounced an early version of

Atlas Shrugged

“unsaleable and unpublishable,” setting her free on the market. She mentioned the book to Hiram Haydn, who had left Bobbs- Merrill for Random House. Despite Random House’s liberal reputation, Rand was impressed that they had published Whittaker Chambers’s

Witness

and was willing to give them a hearing. She was also interested in having her old editor, Archie Odgen, onboard. Ogden was no longer employed by a publishing house but had agreed to work with Viking as the editor of her novel, should they publish it. Rand was unsure if this ad hoc arrangement would be right for her prized creation.

Haydn and his boss, the legendary Bennett Cerf, played their cards perfectly. They proposed a lunch with Rand simply to learn more about the book. When Rand’s agent torpedoed the plan for being unfair to other publishers, they had another suggestion to make. What if Rand had lunch with every seriously interested publisher? They were even amenable to a dual submission, should Rand choose. At lunch Haydn, Cerf, and a third editor quizzed Rand about the implications of her book. One ventured that if the novel was an uncompromising defense of capitalism, it would necessarily contradict Christian morality. Rand was pleased with the observation. Random House was offering her respect and understanding, if not agreement. By the end of the lunch she had essentially made up her mind. It took Random House a similarly short time to make an offer on the manuscript. Haydn himself found Rand’s philosophy repugnant, but could tell that

Atlas Shrugged

had “best-seller” stamped on it. He and Cerf were sure it would be an important and controversial book and told Rand to name her terms.

60

The months from the completion of

Atlas Shrugged

in March to its publication in October 1957 were a rare idyll for Rand. Random House treated her reverently. Cerf asked her to speak personally to the sales staff about the book, a special honor for an author. When she refused to accept any editorial changes whatsoever the house acquiesced. No longer “with novel,” Rand was relaxed, happy, and triumphant.

61

She and Branden continued their affair, settling into their blended roles as lovers and intellectual collaborators. It was the calm before the storm.

PART III

Who Is John Galt? 1957–1968

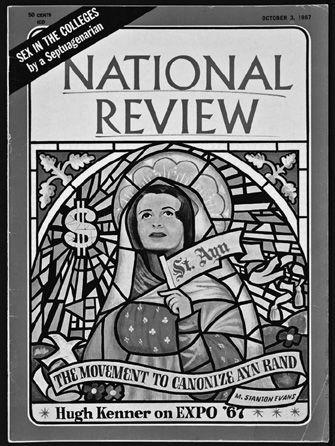

Rand on the cover of

National Review

, October 1967 © 1967 by

National Review

, 215 Lexington Avenue, New York, NY 10016.

CHAPTER SIX

Big Sister Is Watching You

WHEN

THE FOUNTAINHEAD

was published Rand was an obscure author, unknown to the literary world. By contrast, legions awaited

Atlas Shrugged

. Buzz had been building about the book.

The Fountainhead

’s astounding sales, still strong a decade after publication, seemed to guarantee that her next work would be a blockbuster. Rand herself was becoming a mythological figure in New York, a vivid and memorable character rarely seen by those outside the Collective. Random House fed the beast with a series of teaser ads, a press conference, and a prominent display window on Madison Avenue. The word was out: a major new novel was on the way.

Rand and the Collective too were breathless with anticipation. Rand told her followers she would face criticism: she steeled herself for attack. The Collective did not take her warnings seriously. Carried away by the power of Rand’s words, they were convinced it would only be a matter of years before Objectivism conquered the world. Robert Hessen, a new member of Rand’s circle, remembered the feeling: “We were the wave of the future. . . . Objectivism would sweep everything in its path.”

1

With such a buildup, Rand and those closest to her were utterly unprepared for the fierce condemnation that greeted the book. “Is it a novel? Is it a nightmare?”

Time

magazine asked in a typically snide review.

2

A few right-leaning magazines and newspapers praised

Atlas Shrugged,

but taken as a whole the harsh verdict was clear. Rand was shattered. More than anything else, she wanted a defender, an intellectual equal who would trumpet her accomplishment to the world. None appeared.

As it turned out, there was not one

Atlas Shrugged,

but many. Hostile critics focused relentlessly on Rand’s treatment of human relationships, her anger, her bitterness. Business owners and capitalists saw instead her celebration of industry, her appreciation for hard work and

craftsmanship, her insight into the dynamics of free markets. Students and younger readers thrilled to her heroic characters and were overjoyed to discover the comprehensive and consistent philosophy of Objectivism. The aftermath of the book’s publication taught Rand that she was truly on her own. Her path to intellectual prominence would not be typical, conventional, or easy. In retrospect, it seems obvious: Rand would do it her way.

Taken at the level of a story,

Atlas Shrugged

is a moral fable about the evils of government interference in the free market. The novel is set in a dystopian world on the brink of ruin, due to years of liberal policymaking and leadership. The aggrandizing state has run amok and collectivism has triumphed across the globe. Rand’s decaying America resembles the Petrograd of her youth. The economy begins to crumble under the pressure of socialist policies, and food shortages, industrial accidents, and bankruptcies become commonplace. Gloom and dread pervade the country. Fatalistic and passive, citizens can only shrug and ask the empty question, a catchphrase of the novel, “Who is John Galt?”

Rand shows us this world through the eyes of two primary characters, Dagny Taggart and Hank Rearden. Both are gifted and inventive business owners who struggle to keep their enterprises afloat despite an ever-growing burden of government regulation. Starting off as business partners, the single Dagny and married Hank soon become lovers. Strong, handsome, and dynamic, Dagny and Hank contrast sharply with Rand’s villains, soft and paunchy government bureaucrats and corrupt business owners who seek favors from the politicians they have bought. Dagny and Hank’s enemies begin with laws that restrict competition, innovation, and cross-ownership of businesses, and by the end of the novel have nationalized railroads and the steel industry. In a detail reminiscent of Soviet show trials, when the government expropriates private property it forces the owners to sign a “gift certificate” framing the action as a patriotic donation.

Rebelling against this strangulation by the state, the creative minds of America go “on strike,” and throughout the course of the story all competent individuals in every profession disappear. Until they are granted

complete economic freedom and social respect, the strikers intend to withhold their talents from society. To Dagny and Hank, who do not understand the motivation of the strikers, the mysterious disappearance of their counterparts in every industry is yet another burden to bear. The man masterminding this strike, John Galt, does not appear as a main character until more than halfway through the 1,084-page novel. Although Galt is only a shadowy figure for most of the book, he is the culmination of Rand’s efforts to create a hero. Like Howard Roark, Galt is a man of physical beauty, outsize genius, and granite integrity. He has created a motor run by static electricity that will revolutionize science and industry, but keeps it a secret lest it be captured by the collectivists. Once Galt enters the story, he begins pursuing Dagny and Hank, the last two competent industrialists who have not joined the strike. He wants to lure them to his mountain hideaway, Galt’s Gulch, where the strikers have created a utopian free market society.

The dramatic tension in

Atlas Shrugged

comes from Rand’s underlying belief that evil is impotent unless aided by the good. Galt must teach Dagny and Hank that by refusing to join the strike, they are aiding and abetting the collectivist evils that have overcome their country. Without “the sanction of the victim”—the unwitting collaboration of exceptional individuals—Rand’s collectivists would be powerless.

3

The book tips into philosophical territory as Galt makes his case to Dagny and Hank, aided by a cast of colorful secondary characters such as Francisco Domingo Carlos Andres Sebastián D’Anconia, a renegade aristocrat. Here the novel becomes more than a parable about capitalism. Rand’s characters learn to reject the destructive sacrificial ethics and devotion to community they have been taught, and instead join the ethical selfishness of Galt’s strike.

As in

The Fountainhead,

Rand redefined morality to fit her vision. It was moral to make money, to work for oneself, to develop unique talents and skills. It was also moral to think, to be rational: “A rational process is a moral process,” Galt lectures his audience. “Thinking is man’s only basic virtue, from which all the others proceed” (944). It is immoral to ask for anything from others. Galt’s strikers swear an oath that encapsulates Rand’s ethics: “I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine” (680).

Throughout the novel Hank Rearden serves as Rand’s object lesson, her example of philosophy in the real world. Although rational in his business dealings, in his personal life he is crippled by guilt and a feeling of obligation toward his parasitic family. These feelings also keep him toiling in an economy controlled by his enemies rather than joining the strike. Only when Rearden realizes that rationality must extend to all spheres of his life, and that he does not owe either his family or the wider society anything, can he truly be free. Withdrawing the “sanction of the victim,” he joins Galt’s Gulch. Dagny is a harder case, for she is truly passionate about her railroad. Even after embarking on an affair with Galt, she resists joining the strike. Only at the end of the novel does she realize that she must exercise her business talents on her own terms, not on anyone else’s. When she and Rearden finally join the strike, the ending is swift. Without the cooperation of the competent, Rand’s bad guys quickly destroy the economy. Irrational, emotional, and dependent, they are unable to maintain the country’s vital industries and use violence to subdue an increasingly desperate population. At the novel’s end they have ushered in a near apocalypse, and the strikers must return to rescue a crumbling world.

Outside of the academic and literary worlds

Atlas Shrugged

was greeted with an enthusiastic reception. The book made Rand a hero to many business owners, executives, and self-identified capitalists, who were overjoyed to discover a novel that acknowledged, understood, and appreciated their work. The head of an Ohio-based steel company told her, “For twenty-five years I have been yelling my head off about the little realized fact that eggheads, socialists, communists, professors, and so-called liberals do not understand how goods are produced. Even the men who work at the machines do not understand it. It was with great pleasure, therefore, that I read ‘Atlas.’”

4

Readers such as this welcomed both the admiring picture Rand painted of individual businessmen and her broader endorsement of capitalism as an economic system.

Atlas Shrugged

updated and formalized the traditional American affinity for business, continuing the pro-capitalist tradition Rand had first encountered in the 1940s. She presented a spiritualized version of America’s market system, creating a compelling vision of capitalism that drew on traditions of self-reliance and individualism but also presented a for ward-looking, even futuristic ideal of what a capitalist society could be.

Throughout the novel Rand demonstrated a keen appreciation for capitalism’s creative destruction and a basic comfort with competition and flux. A worker on Taggart Transcontinental admires the prowess of a competitor, stating, “Phoenix-Durango is doing a brilliant job” (16). By contrast, her villains long for the security of a static, planned economy. One bureaucrat declares, “What it comes down to is that we can manage to exist as and where we are, but we can’t afford to move! So we’ve got to stand still. We’ve got to stand still. We’ve got to make those bastards stand still!” (503). Rand lavished loving attention on railroad economics, industrial processes, and the personnel problems of large companies. She had conducted extensive research on railroads while writing the book, and her fascination with and respect for all industry shone through the text. As she described the economy, Rand avoided the language of science or mechanism, employing instead organic metaphors that present the economy as a living system nurturing to human creativity and endeavor. To her, money was “the life blood of civilization” (390) and machines the “frozen form of a living intelligence”(988). The market was the repository of human hopes, dreams, talents, the very canvas of life itself.