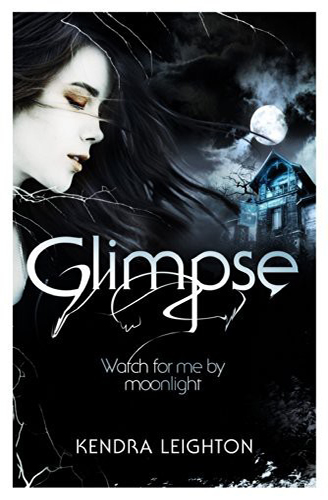

Glimpse

Authors: Kendra Leighton

Tags: #Teen & Young Adult, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Fantasy

Kendra Leighton

was born in 1983 and spent most of her childhood absorbed in books. After completing a degree in English Literature and a post-graduate in Education, she taught English in China, Spain and in UK middle-schools. She rediscovered her love for Noyes’s ‘The Highwayman’ while teaching the poem to thirteen-year-olds, and for YA fiction while browsing the school library. In 2008 she left teaching to co-found a chocolate company, giving her the time to indulge in her true passion: books. While making chocolate she listens to audio books. The rest of the time, she can usually be found writing YA or studying the writing craft.

Constable & Robinson Ltd.

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Much-in-Little, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2014

Copyright © Kendra Leighton, 2014

The right of Kendra Leighton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual events or locales is entirely coincidental.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-4721-1034-3 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-4721-1044-2 (ebook)

Printed and bound in the UK

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For my dad, whose story ended as this one began

PART ONE

I

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees,

The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,

The road was a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor,

And the highwayman came riding –

Riding – riding –

The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn-door.

II

He’d a French cocked-hat on his forehead, a bunch of lace at his chin,

A coat of the claret velvet, and breeches of brown doe-skin;

They fitted with never a wrinkle: his boots were up to the thigh!

And he rode with a jewelled twinkle,

His pistol butts a-twinkle,

His rapier hilt a-twinkle, under the jewelled sky.

III

Over the cobbles he clattered and clashed in the dark inn-yard,

And he tapped with his whip on the shutters, but all was locked and barred;

He whistled a tune to the window, and who should be waiting there

But the landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot into her long black hair.

IV

And dark in the dark old inn-yard a stable-wicket creaked

Where Tim the ostler listened; his face was white and peaked;

His eyes were hollows of madness, his hair like mouldy hay,

But he loved the landlord’s daughter,

The landlord’s red-lipped daughter,

Dumb as a dog he listened, and he heard the robber say –

V

‘One kiss, my bonny sweetheart, I’m after a prize to-night,

But I shall be back with the yellow gold before the morning light;

Yet, if they press me sharply, and harry me through the day,

Then look for me by moonlight,

Watch for me by moonlight,

I’ll come to thee by moonlight, though hell should bar the way.’

VI

He rose upright in the stirrups; he scarce could reach her hand,

But she loosened her hair i’ the casement! His face burnt like a brand

As the black cascade of perfume came tumbling over his breast;

And he kissed its waves in the moonlight,

(Oh, sweet, black waves in the moonlight!)

Then he tugged at his rein in the moonlight, and galloped away to the West.

PART TWO

I

He did not come in the dawning; he did not come at noon;

And out o’ the tawny sunset, before the rise o’ the moon,

When the road was a gypsy’s ribbon, looping the purple moor,

A red-coat troop came marching –

Marching – marching –

King George’s men came marching, up to the old inn-door.

II

They said no word to the landlord, they drank his ale instead,

But they gagged his daughter and bound her to the foot of her narrow bed;

Two of them knelt at her casement, with muskets at their side!

There was death at every window;

And hell at one dark window;

For Bess could see, through her casement, the road that he would ride.

III

They had tied her up to attention, with many a sniggering jest;

They had bound a musket beside her, with the barrel beneath her breast!

‘Now, keep good watch!’ and they kissed her.

She heard the dead man say –

Look for me by moonlight;

Watch for me by moonlight;

I’ll come to thee by moonlight, though hell should bar the way!

IV

She twisted her hands behind her; but all the knots held good!

She writhed her hands till her fingers were wet with sweat or blood!

They stretched and strained in the darkness, and the hours crawled by like years,

Till, now, on the stroke of midnight,

Cold, on the stroke of midnight,

The tip of one finger touched it! The trigger at least was hers!

V

The tip of one finger touched it; she strove no more for the rest!

Up, she stood up to attention, with the barrel beneath her breast,

She would not risk their hearing; she would not strive again;

For the road lay bare in the moonlight;

Blank and bare in the moonlight;

And the blood of her veins in the moonlight throbbed to her love’s refrain.

VI

Tlot-tlot; tlot-tlot!

Had they heard it? The horse-hoofs ringing clear;

Tlot-tlot, tlot-tlot

, in the distance? Were they deaf that they did not hear?

Down the ribbon of moonlight, over the brow of the hill,

The highwayman came riding,

Riding, riding!

The red-coats looked to their priming! She stood up, straight and still!

VII

Tlot-tlot

, in the frosty silence!

Tlot-tlot

, in the echoing night!

Nearer he came and nearer! Her face was like a light!

Her eyes grew wide for a moment; she drew one last deep breath,

Then her finger moved in the moonlight,

Her musket shattered the moonlight,

Shattered her breast in the moonlight and warned him – with her death.

VIII

He turned; he spurred to the West; he did not know who stood

Bowed, with her head o’er the musket, drenched with her own red blood!

Not till the dawn he heard it, his face grew grey to hear

How Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

The landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Had watched for her love in the moonlight, and died in the darkness there.

IX

Back, he spurred like a madman, shrieking a curse to the sky,

With the white road smoking behind him and his rapier brandished high!

Blood-red were his spurs i’ the golden noon; wine-red was his velvet coat,

When they shot him down on the highway,

Down like a dog on the highway,

And he lay in his blood on the highway, with the bunch of lace at his throat.

X

And still of a winter’s night, they say, when the wind is in the trees,

When the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,

When the road is a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor,

A highwayman comes riding –

Riding – riding –

A highwayman comes riding, up to the old inn-door.

XI

Over the cobbles he clatters and clangs in the dark inn-yard;

He taps with his whip on the shutters, but all is locked and barred;

He whistles a tune to the window, and who should be waiting there

But the landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot into her long black hair.

Alfred Noyes, 1906

GOALS (HOW TO BECOME NORMAL)

NO NIGHTMARES

NO GLIMPSES

STOP WORRYING DAD

GET FRIENDS

I scrutinized Miss Mahoney’s face as she read. Her eyebrows had been raised for a few minutes now. I ran through each of the four points in my head. She must have read them ten times. I wished I knew what she was thinking.

She lay the paper face down on the desk and spread her hands over it as though it might fly up and hit her in the face.

‘Liz,’ she began.

My stomach tensed. She didn’t like it. I’d learnt early on in our year of meetings that her ‘I’m being serious now’ voice was not a good sign.

‘This list . . .’

She fixed her gaze on a point somewhere over my left shoulder instead of meeting my eye. She really didn’t like it.

‘This list . . . Now, it goes without saying that I am happy for you. Delighted for you. I wouldn’t normally advise students to move schools at this point in their studies, but I know being at Jameson Secondary has not been easy. I can understand why you’re itching to get away.’ She finally turned her gaze to me and I made an effort to stop fidgeting in my chair. ‘However, this whole obsession with being normal . . .’

I folded my arms around me.

‘“Normal” is meaningless, Liz. You are only as normal as you feel inside.’

I sighed. ‘That’s the point,’ I said, picking my satchel off the floor and resting it on my knee.

‘I’m pleased you’ve written down some goals like I asked you to, but I was thinking of something more achievable. More . . .’ She waved her hands as if trying to pull the right words to her.

‘These are achievable, miss. Well, the first three anyway.’

The corners of her mouth drooped. ‘How?’

‘I’ll be gone from this school. I’ll be living in a different house.’

‘And the nightmares will stop, just like that? Your “Glimpses”—’ she made quotation marks in the air with her fingers ‘—will stop?’

‘Yes.’ My heart was pounding, the way it always did when someone tried to talk to me about my Glimpses. I glanced pointedly towards the door.

Miss Mahoney sighed and leaned back in her chair. She looked at me for a long moment. I wrapped the lace hem of my dress around my finger and tried to keep my face calm.

‘I know you don’t want to hear this again,’ she said, ‘but I need to remind you that you can’t expect to run from your problems, as if they’re separate from you. I’m concerned that you’re setting yourself up for disappointment—’

I stood up, cutting her short with the squeak of my chair on the tiles. I pressed my satchel to my chest like a shield. ‘Well, you can stop worrying about me now, miss.’ I pursed my lips together and stared at an ink stain on her desk, not wanting to see the sympathy I knew would be in her eyes.

She held my ‘Normality List’ out to me. ‘I just don’t want you to have unrealistic expectations.’

I took the paper and pushed it into the outside pocket of my bag. ‘I’m going to be fine.’

‘I hope so, Liz.’

The lunch bell rang, punctuating the end of her sentence. The corridor outside her office exploded with the noise of classroom doors banging open, the pound and squeak of feet racing to join the lunch queue, ‘No running!’ yelled by a teacher.

My stomach clenched. But then I remembered – this was my last lunchtime here; my very last – and my tension eased. I reached for the door handle. ‘Bye, then. And thanks.’

Miss Mahoney’s raised voice followed me as I stepped into the flow of bodies in the corridor. ‘Bye, Liz. I’m only an email away if you need me.’

I gave her a last smile as the door swung shut behind me. I won’t be emailing, I thought. Four hours from now, the nightmare of my school life here would be over. Five weeks from now I’d be leaving this town for good. Things could only get better.

I looked down, held my satchel to my chest like a battering ram, and headed through the corridors. The crowd thinned as I moved away from the dining hall. By the time I’d reached my locker, I was as alone as I ever was at Jameson Secondary.