Girl Walks Into a Bar (4 page)

Read Girl Walks Into a Bar Online

Authors: Rachel Dratch

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Topic, #Relationships, #Humor, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

The year was 1984

, and I, an eighteen-year-old Jewish girl from suburban Boston, was arriving at my new campus, Dartmouth College, where I was about to encounter a species of human I had never met in my life. I speak of the WASP. Not just one WASP, a swarm of WASPS: blond and beautiful women wearing pearls, and the daughters of oil barons from Texas. Gorgeous adolescent males from Deerfield and Exeter who looked as if they’d walked off the pages of a J.Crew catalog. The

Dartmouth Review

, a super-right-wing college newspaper, had a big voice on campus. Laura Ingraham, the ultraconservative commentator, was a vocal student there and she was heading up the

Review

, along with future speechwriters for George Bush, such as Dinesh D’Souza. The following year, members of the

Review

would destroy the antiapartheid shanties that had been constructed on the green. Wait a minute! What was I doing here in this hotbed of right-wing delights? Like many seventeen-year-olds looking at schools, my main criterion had been “This is a pretty campus!” Plus, every student I met seemed to love the

place with a devotion usually reserved for a cult. Walking around the campus as a prospective student, I was sucked in, seeing all the dreamy, perfect-looking boys who looked like they were straight out of a teen movie. When I got there, I eventually realized that the guys who look like that in movies are usually the antagonists to the goofy underdogs whom everyone’s rooting for—the campus had its fair share of James Spaders from

Pretty in Pink

, Neidermeyers from

Animal House

, and faux Neidermeyers from

Revenge of the Nerds

. I think I would have been happier in college with the Duckies, the Blutos, and the Nerds, and in spite of its academic reputation, back in the eighties, there weren’t many Nerds at Dartmouth.

I got my first glimpse of what a culture shock college would be on my very first Dartmouth experience—the freshman trip. These are hiking and camping trips you take before school starts, to get into the groove and supposedly have fun. I signed up for the easiest, level-1 trip because I’m a terrible athlete. Upon meeting my fellow freshman-trippers, I discovered that the most beautiful girl I had ever seen was in my group. This chick was total Dartmouth material. She was named Abigail and was a natural-blond species the likes of which did not exist in my high school. Although she was perfectly friendly and nice to me, I took one look at her and was like, “Oh, nooo! I think I picked the wrong school!” When I was eighteen, I didn’t have the faith in myself to listen to my gut feeling. I don’t mean to say that I saw one beautiful girl and freaked out—it was the

type

of beautiful girl: the confidence, the breeziness, the probable lineage connecting her to the

Mayflower

. Oh, and as a side note, she was doing our level-1 trip on

crutches

because she had sprained her ankle being a champion tennis player. Otherwise, she would have been on a real hiking trip. You should have seen the guys fighting to carry her over the streams.

I had come from my hometown public high school with my funny friends and Irish and Italian characters, and here I was with people who had last names for first names, like Farns-worth and Chadwell. Where were the Sullys? The Smittys? (They were at UMass or Plymouth State.) Now, I know it’s not like I was coming from the ghet-to. My town, back then, was about a third Irish, a third Italian, and a third Jewish, and our parents were largely second generation who had managed to move out to the burbs. Overall, I felt quite comfortable in high school. All had been rosy in my world, or, as some people from my high school might say, everything was wicked pissah.

For this next section, if you happen to have a cassette tape of REM’s “Murmur” lying around, throw it into your boom box, which you also surely have on hand, and press

PLAY

, because that was the sound track I had on constant loop for much of my time at Dartmouth, where I was feeling none of the comfort level I had in high school. I was rejected from the two plays I auditioned for during the fall and winter trimesters. I thought I really might have had a shot in the winter—they were doing William Inge’s

Picnic

and I was auditioning to play Millie, the more plain younger sister of the beautiful Madge. (Madge, no joke, was played by Freshman Trip Abigail.) As I was walking onto the stage to audition, the director said of the girl who had just auditioned before me, “Well, I think we found our Millie!”

The Greek system was huge at Dartmouth and though I never aspired to be in a sorority, it seemed like “Everyone’s doin’ it!” so I went ahead and rushed. I was not invited back to any sororities after the first round of rush. Lest you think I had social issues, this one really baffled me, because making friends had never been a problem for me. I think I was wearing the wrong dress—a little corduroy number. Yes, I was rocking a corduroy dress, with long sleeves, that I thought was cute but clearly was all wrong. I felt as if I had now been literally cast out to match the general figurative outcast feeling I already had there. In addition, I was also rejected by the damn

Freshman Cabaret

—a little medley of dumb sketches and stuff that anyone who’d ever set foot on a stage, or even never set foot on a stage and just had some general enthusiasm, could be in! You can see how I may not have been feeling in tip-top form. Oh, and I was also rejected from the a cappella singing group the Decibelles (!), but that rejection I’m sure I deserved. Throw into this mix that I had a roommate who was, um, let’s call it “making love” to anything that moved, at rates that made me wonder if she was going for some sort of plaque above the large fireplace in the student center. I was on the other end of the spectrum, pure as the Hanover snow, which was probably still about five feet high in April.

After a summer of being back home working as a bus boy at the Magic Pan in the Burlington Mall (Do you remember the Magic Pan? Home of that newfangled eighties delicacy, the

crepe

! It’s what passed for exotic French food in the world of the suburbs), I returned to Dartmouth for sophomore fall to discover that I had a bad lottery number for housing, so I had

to move from my old-school, beautiful, centrally located ivy-covered dorm down to a faraway land called the River Cluster—an ugly group of seventies-looking cinder-block towers that was the equivalent of Siberia. No one hung out at the River Cluster. You just went there to sleep. I had been assigned a roommate, but she somehow escaped, and as a measure of how depressed I was to be there, I never even moved my stuff into her larger area of the room. I stayed in my tiny side of the room and did nothing with the larger part, which could have been turned into some sort of fun living area, I suppose, but that would mean you’d have to somehow lure people down to the River Cluster, which wasn’t going to happen. As I said, I was starting to feel depressed, something I hadn’t experienced previously, so much so that I worked up my courage to go to the school counselor. I was really nervous about it. This meant I actually had a

problem.

I no longer had the ability to keep fooling myself that I liked this place.

I walked into the counselor’s office and had another instant gut feeling. I took one look at this guy and was like, “Nope!” I wanted some hip, young

warm

person that I would feel comfortable talking to. I had never been to a counselor. I didn’t know what to expect. Out walked a man who was older than my dad, with gray balding hair, a powder-blue sweater, and the neutral expression passed down from generation upon generation of the salt-of-the-earth, granite-in-your-veins New Englanders. At the time, though, with my lack of belief in my instincts, a subtle thought merely wafted through my brain—almost like a scene from

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

, a tiny voice said, “He’s one of them!”

The counseling session was completely fruitless. I think I said something to the effect that I was just not finding anyone here that I liked, that this wasn’t my scene and I was thinking of transferring. He would respond only by asking me about my family and kept trying to dig around with an “Is everything OK at home?” tactic. “YES! EVERYTHING’S GREAT AT HOME!” I wanted to shout back. “THAT’S THE PROBLEM! Sully’s there! And Smitty! And I think I was happier working at the Magic Pan!” That may sound strange since I was fortunate enough to be at this esteemed campus, but when you aren’t happy, you aren’t happy, and the detriments were vastly outweighing the blessings.

I was still thinking of transferring. I think I had gone so far as to pick up some applications for other schools, and that’s when, during my sophomore winter, I saw the Dartmouth improv group perform. “Ooh!” I thought. “I could do that!” I had always gravitated toward comedy in theater anyway. I got to sit in on one of their rehearsals through a friend from acting class. They invited me to join the group, which was called Said and Done, and it was my salvation. Finally, I had found some people who enjoyed looking foolish and were a bit offbeat and were definitely funny and creative.

Improvisation was the perfect branch of acting for me—it’s perfect for those who don’t like to prepare, or, as one might also call them, the

lazy

. There are rules to improv that can help you be a better improviser, but you don’t have to study for a test or rehearse a monologue. You don’t have to “find your moments” or learn your lines. You are

in

your moment and you make up your

own

lines. If you are any good, your lines are

funny. And they are funnier than anything you could have thought of if you were sitting staring at a computer (back then, that was the Mac 128k) trying to think up some comedy.

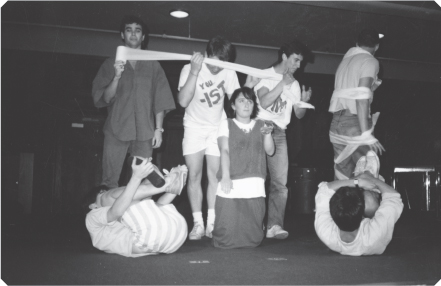

My college improv group doing that mainstay piece of beginning improvisers: the Machine!

At one of the first Said and Done rehearsals I attended, I experienced that thing that happens in improv, when the line comes out of your mouth before your brain has registered what you are about to say. We were doing some sort of group poem about money or something, and I said, “I’m so rich that it’s no surprise, when I’m tired, I get Gucci bags under my eyes.” Now, I’m not saying that is the most brilliant line ever, but hey, I was nineteen years old and I hadn’t experienced the phenomenon before. “How did I think of that?” I wondered. I didn’t feel like I

had

thought of it. It’s a sort of flow that happens when you are completely in the moment and not getting

in your own way. Not

trying

so hard, not planning ahead, just getting out of your own head and letting the magic happen. You could apply this to any activity, of course. You could apply it to life.

The biggest rule of improv is called “Yes And.” Basically, this means that whatever your scene partner says to you, you agree and then add to it. So if you are starting a scene and your partner says, “I made you a birthday cake, Grandma!” you don’t respond, “I’m not your Grandma, and that’s not a cake—it’s an old shoe!” You would get a quick laugh, but you would kill the reality of the scene entirely. A “Yes And” exchange would be: “I made you a birthday cake, Grandma!” “Oh, thank you, dear. I feel thirty-five years young!” By agreeing to what your partner laid out and adding to it, you’ve established a relationship and even given your partner something to play with—that this family has a grandmother who is thirty-five years old—and the scene can develop from there. “Yes And” would serve me well, not only onstage but offstage too. Without my realizing it, “Yes And” would contribute to one major career success and one major life event far down the road from the rehearsal room in Hanover, New Hampshire, during the winter of my sophomore year.

Chicago:

Overnight Success in Ten Years!

By the time

I graduated, I had ferreted out a group of friends who are still a part of my life to this day. I ended up meeting a lot of my Dartmouth friends through the theater department. Then there’s another branch of my guy friends at Dartmouth who all came out of the closet in rapid succession after graduation. (This would begin my long-standing tradition of always having a fab group of gay men to hang with at a moment’s notice.) I knew I didn’t want to go through life thinking, “What if I had tried to become an actor?” I decided I at

least wanted to give it a shot. I had no idea

how

to go about giving acting a shot, though. There was no set plan like it seemed all my classmates had who were applying to med school or law school or going into the corporate world. My improv group had done an exploratory trip to Chicago over the summer to check it out, and I decided to move there after graduating to try to get into the improv comedy mecca of the country, the Second City.