Gimme Something Better (71 page)

Read Gimme Something Better Online

Authors: Jack Boulware

I don’t know if the magazine mentioned it, I don’t even remember. This comment Web site came up, and everyone told their stories. That was kinda cool. A lot of people, some from around the world.

Jeff Bale:

I posted something on that. Some of Tim’s enemies posted some nasty comments.

I posted something on that. Some of Tim’s enemies posted some nasty comments.

Martin Sprouse:

The mainstream press gave Tim more recognition than the people who were close with him, who shared his ideas.

Rolling Stone

paid their tribute to Tim Yo, when he had nothing to do with

Rolling Stone

. The

San Francisco Chronicle

had a one-liner, where they spelled his name wrong.

The mainstream press gave Tim more recognition than the people who were close with him, who shared his ideas.

Rolling Stone

paid their tribute to Tim Yo, when he had nothing to do with

Rolling Stone

. The

San Francisco Chronicle

had a one-liner, where they spelled his name wrong.

Tim Yo didn’t want anyone to deal with his body when he died. He had this naive idea that if no one claimed his body, the city would just come pick up his body and process him as a John Doe. In theory it sounded good, but it’s like something out of a Humphrey Bogart movie.

The hospice nurse asked us, “Have you made arrangements?” We hadn’t really thought about it. I just reiterated Tim’s plan. And they said, “Uh, that’s ridiculous. You do it that way, the homicide squad’s gonna come out there and yellow-tape the whole place, and check for suspicious death.” So the hospice people hooked us up with a funeral service.

The very next day, I had to go meet with these people and tell them we didn’t want the ashes. They could not understand that. We had to give them extra money. We didn’t want a plaque, we didn’t want to know anything about it. I sat there for an hour, trying to explain this to some funeral director. He thought we were crazy. But I knew this is what Tim would have wanted.

They dumped his ashes out in the bay, with a bunch of other people’s. I told his brother this whole thing, and his brother said, “Wow, that’s so ironic. Because the bastard couldn’t swim.”

55

Rock ’n’ Roll High School

Jello Biafra:

Tim once explained to me why he was a socialist and not an anarchist. He felt there needed to be some kind of government entity, to transfer the wealth from people who had too much to people who have too little. And I think he’s right.

Tim once explained to me why he was a socialist and not an anarchist. He felt there needed to be some kind of government entity, to transfer the wealth from people who had too much to people who have too little. And I think he’s right.

Jeff Bale:

I wish he was still around, so we could argue and listen to records. But he isn’t.

I wish he was still around, so we could argue and listen to records. But he isn’t.

Dave Dictor:

I loved him. I wrote a song for him called “Timmy Yo.”

I loved him. I wrote a song for him called “Timmy Yo.”

Jeff Ott:

He was very Marxist. It took quite awhile to realize how much he had going on. Never been in a band, fairly soft-spoken guy. He’d get angry and argue or whatever, but for the most part, his method of having power in the world was talking with other people, or writing, and handing it over.

He was very Marxist. It took quite awhile to realize how much he had going on. Never been in a band, fairly soft-spoken guy. He’d get angry and argue or whatever, but for the most part, his method of having power in the world was talking with other people, or writing, and handing it over.

Dave Mello:

Tim Yohannan was always that older guy, smoking cigarettes in the corner. He was a quiet guy, but he was very much the guy that organized Gilman—with 14-, 15-, 16-year-olds. It wasn’t like we were really scared of him, but he could chew your face off if he started to yell at you.

Tim Yohannan was always that older guy, smoking cigarettes in the corner. He was a quiet guy, but he was very much the guy that organized Gilman—with 14-, 15-, 16-year-olds. It wasn’t like we were really scared of him, but he could chew your face off if he started to yell at you.

Ben Saari:

Tim was kind of an asshole at meetings, but he really had a concrete vision. About kids creating their own culture and running things themselves.

Tim was kind of an asshole at meetings, but he really had a concrete vision. About kids creating their own culture and running things themselves.

Blag Jesus:

The hippie generation of people were the first to turn around and become the worst kind of capitalists. So the fact that a guy like Tim Yohannan held on and always stayed true to his ideals, that’s a beautiful thing. He deserves to be commended for that.

The hippie generation of people were the first to turn around and become the worst kind of capitalists. So the fact that a guy like Tim Yohannan held on and always stayed true to his ideals, that’s a beautiful thing. He deserves to be commended for that.

You can make fun of him for it, and I did, but he had a sense of humor. If you got rich from an East Bay punk band, you owe everything to Tim Yohannan. He was making a world-renowned magazine. If you had a bumfuck band in Milwaukee, only some people in Milwaukee knew about it. If you had a bumfuck band in the East Bay, everyone all over the world knew about it.

So Tim, in an indirect way, is responsible for making bands like Green Day and Rancid very wealthy. They should fuckin’ have a permanent memorial to the guy. The East Bay punk scene owes everything to him, and a lot of the California punk scene does.

Mike LaVella:

There was a lot of mystery around Tim. He had a daughter. A lot of people didn’t know about that.

There was a lot of mystery around Tim. He had a daughter. A lot of people didn’t know about that.

Kurt Brecht:

A friend of ours lived up near Haight-Ashbury. MDC turned us on to this cool lady, said she was punk-friendly. So every now and then I’d ask her if I could take a shower.

A friend of ours lived up near Haight-Ashbury. MDC turned us on to this cool lady, said she was punk-friendly. So every now and then I’d ask her if I could take a shower.

Her and Tim Yohannan had a baby. They weren’t married. He didn’t ever acknowledge the child. He didn’t want to have children. The girl’s grown up, probably 20 years old, 21, 22.

Martin Sprouse:

Jello called me maybe three years ago, and told me he had met Tim’s daughter in Texas. She wrote me once or twice. I guess she had a lot of anger towards him. She’d never met him.

Jello called me maybe three years ago, and told me he had met Tim’s daughter in Texas. She wrote me once or twice. I guess she had a lot of anger towards him. She’d never met him.

Bill Schneider:

I really wonder what Tim Yohannan’s take on Gilman was, later in life. He seemed to rail against everything the East Bay scene became. He hated that all the bands got popular. I wonder if he was ever able to step back from being bitter to see what really came out of Gilman. He had more foresight than he ever knew.

I really wonder what Tim Yohannan’s take on Gilman was, later in life. He seemed to rail against everything the East Bay scene became. He hated that all the bands got popular. I wonder if he was ever able to step back from being bitter to see what really came out of Gilman. He had more foresight than he ever knew.

Mike LaVella:

He was the machine that drove

MRR

. I can’t believe it’s still going. Now they have

Punk Rock Confidential

to tell them who got married. When that thing came out, I was like, Tim Yohannan is rolling over in his grave. “Blink 182 on the golf course,” or whatever. Oh my god, that would make him sick.

He was the machine that drove

MRR

. I can’t believe it’s still going. Now they have

Punk Rock Confidential

to tell them who got married. When that thing came out, I was like, Tim Yohannan is rolling over in his grave. “Blink 182 on the golf course,” or whatever. Oh my god, that would make him sick.

Kevin Carnes:

Anybody that’s ever been in Gilman, onstage or through the doors, was blessed because of that guy. If he walked in this room, I would run over and kiss him and hug him and say, “Thank you for doing what you do.” Between that space and

Maximum RocknRoll

, that guy left a huge thing.

Anybody that’s ever been in Gilman, onstage or through the doors, was blessed because of that guy. If he walked in this room, I would run over and kiss him and hug him and say, “Thank you for doing what you do.” Between that space and

Maximum RocknRoll

, that guy left a huge thing.

Chicken John:

The man was unbeatable. It doesn’t matter how wrong he was, the guy had an idea and he was gonna stick to it. That is the greatest lesson in life, stick with it. Don’t think about how unfair he was, think about how much

more

unfair someone else would have been.

The man was unbeatable. It doesn’t matter how wrong he was, the guy had an idea and he was gonna stick to it. That is the greatest lesson in life, stick with it. Don’t think about how unfair he was, think about how much

more

unfair someone else would have been.

Think of the contribution he made to our lives. What if he didn’t do it? What if he became an interior decorator instead? What if people like Tim didn’t rise to the occasion? History as we know it would be seriously altered if three people like Tim chose different paths. I’m glad I knew him.

Steve Tupper:

I’ve seen a whole lot of labels come and go over the years, distributors, record stores, radio shows, DJs, fanzines.

Maximum

just keeps going as an institution.

I’ve seen a whole lot of labels come and go over the years, distributors, record stores, radio shows, DJs, fanzines.

Maximum

just keeps going as an institution.

Jello Biafra:

I open up an issue now and it’s almost like reading an issue from 20 years ago. In one way that’s good ’cause there’s still the same energies and concerns, reviews of lots of unknown bands. But reading the letters section, in particular, also reveals the same hang-ups and the same

nya nya nya

, gossip, gossip, gossip.Two demerits for this person for being politically incorrect, three demerits for this one.

I open up an issue now and it’s almost like reading an issue from 20 years ago. In one way that’s good ’cause there’s still the same energies and concerns, reviews of lots of unknown bands. But reading the letters section, in particular, also reveals the same hang-ups and the same

nya nya nya

, gossip, gossip, gossip.Two demerits for this person for being politically incorrect, three demerits for this one.

Martin Sprouse:

I stayed involved until a year after he died. Just to make sure the transition happened well. I look at it from time to time. I talk to those guys. But you know what? They’re fine. They’re doing it right.

I stayed involved until a year after he died. Just to make sure the transition happened well. I look at it from time to time. I talk to those guys. But you know what? They’re fine. They’re doing it right.

Martin Sorrondeguy:

It’s continually being flooded with the newest punk music from everywhere. Things are really similar in the look of the magazine, it’s been pretty linear in that sense. Same paper, still on newsprint. Everyone talks about having the ink on the fingers, so you still get that experience.

It’s continually being flooded with the newest punk music from everywhere. Things are really similar in the look of the magazine, it’s been pretty linear in that sense. Same paper, still on newsprint. Everyone talks about having the ink on the fingers, so you still get that experience.

Jeff Bale:

Tim created such an organizational machine that even after his death it continued functioning like a zombie without a brain that kept stumbling. Frankly that’s kind of the way I see

Maximum RocknRoll

.

Tim created such an organizational machine that even after his death it continued functioning like a zombie without a brain that kept stumbling. Frankly that’s kind of the way I see

Maximum RocknRoll

.

Martin Sprouse:

Much like Gilman, it’s on its tenth generation of organizers. They’re not sticking by these rules because the elders told ’em to. But because it’s the way it should be done, and they agree with it.

Much like Gilman, it’s on its tenth generation of organizers. They’re not sticking by these rules because the elders told ’em to. But because it’s the way it should be done, and they agree with it.

Martin Sorrondeguy:

Maximum RocknRoll

, for me, has always been the pinnacle of what is punk culture, and putting that out there. The radio show still happens in the house weekly. They don’t let too many bands stay there, because people started stealing from the collection. They put some of the really rare records on lockdown. Basically you can sign it out, like an archive or a library. The collection is anywhere between 45 to 60,000 records, something like that.

Maximum RocknRoll

, for me, has always been the pinnacle of what is punk culture, and putting that out there. The radio show still happens in the house weekly. They don’t let too many bands stay there, because people started stealing from the collection. They put some of the really rare records on lockdown. Basically you can sign it out, like an archive or a library. The collection is anywhere between 45 to 60,000 records, something like that.

I’ve heard a lot of young people say, “Fuck

Maximum RocknRoll

.” You don’t even realize how important that magazine was. That was like your

news

. That was what linked you to the rest of the punk goin’ on outside of you and your friends. That’s how you tape-traded with people, that’s how you got zines from people. That’s how you got in touch with bands. You couldn’t click on your computer back then.

Maximum RocknRoll

.” You don’t even realize how important that magazine was. That was like your

news

. That was what linked you to the rest of the punk goin’ on outside of you and your friends. That’s how you tape-traded with people, that’s how you got zines from people. That’s how you got in touch with bands. You couldn’t click on your computer back then.

Jeff Bale:

There’s always gonna be underground bands that release their stuff on underground labels, and I say thank god for that. Because that’s where all the fresh good stuff’s gonna come from. People are gonna buy those records and go see those bands. That’s just the way it’s gonna be. Whether the corporate world takes notice or not is pretty much irrelevant.

There’s always gonna be underground bands that release their stuff on underground labels, and I say thank god for that. Because that’s where all the fresh good stuff’s gonna come from. People are gonna buy those records and go see those bands. That’s just the way it’s gonna be. Whether the corporate world takes notice or not is pretty much irrelevant.

Martin Sprouse:

When I was involved, the whole world was different. The economy was different, punk rock was different.

Maximum

had money. But

Maximum

doesn’t make that much money.

Maximum

gets by.

When I was involved, the whole world was different. The economy was different, punk rock was different.

Maximum

had money. But

Maximum

doesn’t make that much money.

Maximum

gets by.

Martin Sorrondeguy:

It’s still connected with Gilman. They aren’t there all the time, but a lot of the same people that work on Gilman stuff help out with

Maximum

, and vice versa. The magazine’s still coming out, and the magazine still features or covers a band that no one knows. Because it still sticks to that basic thing of Right Now. And that’s really the true essence of punk.

It’s still connected with Gilman. They aren’t there all the time, but a lot of the same people that work on Gilman stuff help out with

Maximum

, and vice versa. The magazine’s still coming out, and the magazine still features or covers a band that no one knows. Because it still sticks to that basic thing of Right Now. And that’s really the true essence of punk.

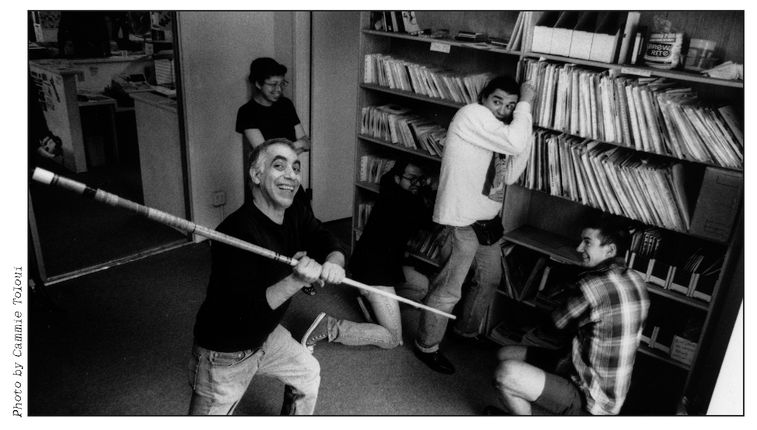

Tim Yo Mama: Yohannan at Epicenter

I saw a dude sittin’ at the bar with his old punk shirt on, slammin’ beers, goin’, “I saw Discharge in ’81.” And a kid said to him, “Yeah, who’ve you seen since then?” It’s like fuckin’ nobody, man. Who cares?

WHO’S WHO

A. C. Thompson:

Former 924 Gilman and Epicenter volunteer. Now toils as an investigative reporter.

Former 924 Gilman and Epicenter volunteer. Now toils as an investigative reporter.

Aaron Cometbus:

Publisher of

Cometbus

fanzine since 1981. He lives with Anna Joy and their three children on a ranch just outside of Laramie, where he is developing alternative energy methods through the use of wind turbines.

Publisher of

Cometbus

fanzine since 1981. He lives with Anna Joy and their three children on a ranch just outside of Laramie, where he is developing alternative energy methods through the use of wind turbines.

Adam Pfahler:

Drummer for Jawbreaker. Currently lives with his wife and two daughters in S.F., where he owns Lost Weekend Video and Blackball Records.

Drummer for Jawbreaker. Currently lives with his wife and two daughters in S.F., where he owns Lost Weekend Video and Blackball Records.

Adrienne Melanie Droogas:

Spitboy and Aus Rotten singer.

Profane Existence

,

Maximum RocknRoll

, and

Slug & Lettuce

columnist, and self-proclaimed punk rock goddess. Currently adventuring in the land down under with the man of her dreams.

Spitboy and Aus Rotten singer.

Profane Existence

,

Maximum RocknRoll

, and

Slug & Lettuce

columnist, and self-proclaimed punk rock goddess. Currently adventuring in the land down under with the man of her dreams.

Al Ennis:

Co-founder of

Maximum RocknRoll

Radio. Still crazy about music. Works as an accountant.

Co-founder of

Maximum RocknRoll

Radio. Still crazy about music. Works as an accountant.

Al Schvitz:

Drummer for MDC.

Drummer for MDC.

Andrew Flurry aka Frog:

S.F. native. Member of Team ’O Fools.

S.F. native. Member of Team ’O Fools.

Andy Asp:

Singer/guitarist for Nuisance. Currently an “aesthetic pilgrim” based in Oakland. “Once a bum, always a bum.”

Singer/guitarist for Nuisance. Currently an “aesthetic pilgrim” based in Oakland. “Once a bum, always a bum.”

Andy Pollack:

Director of the Farm, 1983-1986. Continues as a tax-preparing, musically inclined, San Francisco/Northern California hippie.

Director of the Farm, 1983-1986. Continues as a tax-preparing, musically inclined, San Francisco/Northern California hippie.

Anna Brown:

Berkeley native. What she does is secret.

Berkeley native. What she does is secret.

Anna Joy Springer:

Onetime member of Blatz, Cypher in the Snow, and the Gr’ups. Now an ex-punk Buddhist dyke writer of cross-genre works about the complicated intersections of love and grief. She teaches writing at UC San Diego.

Onetime member of Blatz, Cypher in the Snow, and the Gr’ups. Now an ex-punk Buddhist dyke writer of cross-genre works about the complicated intersections of love and grief. She teaches writing at UC San Diego.

Antonio López:

Co-founder of L.A. punk zine

Ink Disease

and the international zine distributor Desert Moon Periodicals. He is a product of Peace and Conflict Studies at UC Berkeley. Creator of a multicultural media literacy curriculum, Merchants of Culture. Author of

Mediacology

, a book on media education and sustainability. He resides in Rome, Italy, with his partner and daughter.

Co-founder of L.A. punk zine

Ink Disease

and the international zine distributor Desert Moon Periodicals. He is a product of Peace and Conflict Studies at UC Berkeley. Creator of a multicultural media literacy curriculum, Merchants of Culture. Author of

Mediacology

, a book on media education and sustainability. He resides in Rome, Italy, with his partner and daughter.

Audra Angeli-Slawson:

Onetime peace punk and skinhead. Longtime booker. Creator of Stinky’s Peepshow. Director of Incredibly Strange Wrestling. Den mother.

Onetime peace punk and skinhead. Longtime booker. Creator of Stinky’s Peepshow. Director of Incredibly Strange Wrestling. Den mother.

B. A. Lush:

San Francisco punk. Co-founder of Team Lush. Now holds a master’s of science in psychology and has become an authority figure to be rebelled against.

San Francisco punk. Co-founder of Team Lush. Now holds a master’s of science in psychology and has become an authority figure to be rebelled against.

Barrie Evans:

Lead singer of Christ on Parade. Now fronts the Hellbillies.

Lead singer of Christ on Parade. Now fronts the Hellbillies.

Ben de la Torres aka Crimson Baboon:

Gilman volunteer since ’96. Spoken-word artist, singer/drummer for Clan of the Bleeding Eye and Super Happy 9/11 Dance Party. Got clean. Still a punk, still in the pit.

Gilman volunteer since ’96. Spoken-word artist, singer/drummer for Clan of the Bleeding Eye and Super Happy 9/11 Dance Party. Got clean. Still a punk, still in the pit.

Ben Saari aka A-Head:

Moved to the East Bay in 1985, just in time for everything to start sucking. Moved back to the North Bay in 1988, just as everything was becoming awesome. Any greatness he has is purely by association.

Moved to the East Bay in 1985, just in time for everything to start sucking. Moved back to the North Bay in 1988, just as everything was becoming awesome. Any greatness he has is purely by association.

Other books

Gambling on a Dream by Sara Walter Ellwood

No Weapon Formed (Boaz Brown) by Stimpson, Michelle

Footprints in the Butter by Denise Dietz

Sophie's Halloo by Patricia Wynn

Antony and Cleopatra by Colleen McCullough

Brutish Lord of Thessaly (Halcyon Romance Series Book 4) by Rachael Slate

Every Rose by Halat, Lynetta

Lady Emma's Dilemma (9781101573662) by Woodward, Rhonda

Dustin's Gamble by Ranger, J. J.