Gimme Something Better (40 page)

Read Gimme Something Better Online

Authors: Jack Boulware

Jello Biafra:

I was involved in Punkvoter. Of course the more radical-than-thou got down on me. “What the hell are you doing getting involved with Fat Mike, that motherfucking sellout, blah blah blah.” Then I thought, hey, wait a minute. He was born rich, is rich, but he’s putting a lot of his own money into this because he gives a shit. He always did, if you look at his background closely.

I was involved in Punkvoter. Of course the more radical-than-thou got down on me. “What the hell are you doing getting involved with Fat Mike, that motherfucking sellout, blah blah blah.” Then I thought, hey, wait a minute. He was born rich, is rich, but he’s putting a lot of his own money into this because he gives a shit. He always did, if you look at his background closely.

I realized that Punkvoter with Fat Mike running the show would reach way more people than Punkvoter with Jello Biafra running the show. And if that meant working with people who were really into Howard Dean, or wanting a Democrat to win just so Bush wouldn’t be in there—I don’t agree with that, but I’m willing to work with them. I’m willing to work with people more moderate than I am, to help achieve radical change.

Mike LaVella:

I ran into him in Austin. He was like, “Mike, can we count on you? Will you get behind it?” It was like he was campaigning. He was really serious. And then I saw him at Stinky’s Peepshow right after Bush got elected. I said, “Dude, sorry about the election.” He said, “Oh, I don’t care.”

I ran into him in Austin. He was like, “Mike, can we count on you? Will you get behind it?” It was like he was campaigning. He was really serious. And then I saw him at Stinky’s Peepshow right after Bush got elected. I said, “Dude, sorry about the election.” He said, “Oh, I don’t care.”

Fat Mike:

I feel that we made it okay to talk about politics again in the music scene. A lot of bands were doing it. Bruce Springsteen. Dixie Chicks. But our music scene, which had always been political, hadn’t been in the last ten years. Now Green Day is political. Blink 182, the most pop band ever, was stumping for John Kerry. A lot of bands were scared at first, but a lot of bands joined forces. That was the most important thing that we did. We got a few hundred punk bands to make the same stand against the Bush administration.

I feel that we made it okay to talk about politics again in the music scene. A lot of bands were doing it. Bruce Springsteen. Dixie Chicks. But our music scene, which had always been political, hadn’t been in the last ten years. Now Green Day is political. Blink 182, the most pop band ever, was stumping for John Kerry. A lot of bands were scared at first, but a lot of bands joined forces. That was the most important thing that we did. We got a few hundred punk bands to make the same stand against the Bush administration.

Jello Biafra:

I respect Mike and what he did with Punkvoter publicly. But I really disagree with his decision to pull out. It had strong enough legs, he could have let it grow on its own, which in a way it has. The seeds for a large part of the Obama movement were planted by Punkvoter. In fact, one of the main Internet and text message organizers for Obama was the old political director of Punkvoter.

I respect Mike and what he did with Punkvoter publicly. But I really disagree with his decision to pull out. It had strong enough legs, he could have let it grow on its own, which in a way it has. The seeds for a large part of the Obama movement were planted by Punkvoter. In fact, one of the main Internet and text message organizers for Obama was the old political director of Punkvoter.

Fat Mike:

We got the ball rolling and that’s all I wanted to do in the first place. Organize all the bands I knew to take a stand. And now everybody is. So what’s my job now?

We got the ball rolling and that’s all I wanted to do in the first place. Organize all the bands I knew to take a stand. And now everybody is. So what’s my job now?

31

A Chronology for Survival

Fat Mike:

I lived in S.F. but I used to go to a lot of house parties in the East Bay in the ’80s. Christ on Parade and Neurosis and Op Ivy—that was my generation. I knew all those guys. They always used to say, “Mike, you’re out here again!” ’Cause the best parties were out in the East Bay. Half the best shows were in warehouses.

I lived in S.F. but I used to go to a lot of house parties in the East Bay in the ’80s. Christ on Parade and Neurosis and Op Ivy—that was my generation. I knew all those guys. They always used to say, “Mike, you’re out here again!” ’Cause the best parties were out in the East Bay. Half the best shows were in warehouses.

Adrienne Droogas:

I was still in high school and living with my parents when I went to New Method, the warehouse started by Crucifix back in the ’80s. By that time it was Christ on Parade, A State of Mind, Clown Alley.

I was still in high school and living with my parents when I went to New Method, the warehouse started by Crucifix back in the ’80s. By that time it was Christ on Parade, A State of Mind, Clown Alley.

Dave Ed:

New Method was a bunch of really scruffy-looking punks, wearing dark clothing. Crass, dreadlocks, vegetarianism. It was pretty shocking, the size of the shows they got away with. The cops just didn’t care. Emeryville was still no-man’s-land back then.

New Method was a bunch of really scruffy-looking punks, wearing dark clothing. Crass, dreadlocks, vegetarianism. It was pretty shocking, the size of the shows they got away with. The cops just didn’t care. Emeryville was still no-man’s-land back then.

Noah Landis:

I spent a lot of time there. Those guys were several years older than me. They were living in a rotting warehouse, went on rent strike and took it over. That was the most empowering thing I had ever seen. These guys were living outside the grid 24/7. That was a mind-blowing revelation about what punk rock could be. I did a lot of growing up. I couldn’t be a kid around them and spout off stuff that was overopinionated and underinformed. I had to pay attention.

I spent a lot of time there. Those guys were several years older than me. They were living in a rotting warehouse, went on rent strike and took it over. That was the most empowering thing I had ever seen. These guys were living outside the grid 24/7. That was a mind-blowing revelation about what punk rock could be. I did a lot of growing up. I couldn’t be a kid around them and spout off stuff that was overopinionated and underinformed. I had to pay attention.

Eric Ozenne:

My first show was Christ on Parade, the Descendents and 7 Seconds. It was the coolest thing in the world, but I was scared shitless because I was 15 and I was from the Valley. Christ on Parade had a whole rainbow assortment of hairdos. Nohawks, twinhawks, mohawks. Everybody had ripped-up clothes and their music was really dark. I loved it.

My first show was Christ on Parade, the Descendents and 7 Seconds. It was the coolest thing in the world, but I was scared shitless because I was 15 and I was from the Valley. Christ on Parade had a whole rainbow assortment of hairdos. Nohawks, twinhawks, mohawks. Everybody had ripped-up clothes and their music was really dark. I loved it.

Noah Landis:

This super-tall guy with a big mohawk named Barrie Evans worked at Blondie’s. He was in a band with some guys out in Hayward called Teenage Warning. The singer was Kevin Reed. He was amazing—just this screaming ball of sweat and hatred.

This super-tall guy with a big mohawk named Barrie Evans worked at Blondie’s. He was in a band with some guys out in Hayward called Teenage Warning. The singer was Kevin Reed. He was amazing—just this screaming ball of sweat and hatred.

When their guitar player Jim Lyon quit, he asked me to come try out. I learned their songs—they were really fast and straightforward. Barrie picked me up from my mom’s house on a motorcycle and drove me to BART. He showed me how to hop the gate by the elevator. We played at Ruthie’s Inn. My very first show with Teenage Warning—Bill Collins, who taught me to play guitar, was front and center, heckling me the whole time.

When Teenage Warning dissolved, Barrie got together with the drummer and the bass player of Treason, and they brought me into the fold. Malcolm came up with the name Christ on Parade.

Kate Knox:

Christ on Parade had this sound, along with their politics that hit your heart. It was how you felt about the world. They spoke to you.

Christ on Parade had this sound, along with their politics that hit your heart. It was how you felt about the world. They spoke to you.

Noah Landis:

“Landlord Song” was about the guy who owned the New Method building. The idea of ownership of space was just ridiculous to us, so “End of the month, rent is due, tell your landlord, ‘Fuck you,’ ” that came from real life. You can hear how young everybody was when they were writing these things, but the energy and the attitude was pretty fuckin’ awesome.

“Landlord Song” was about the guy who owned the New Method building. The idea of ownership of space was just ridiculous to us, so “End of the month, rent is due, tell your landlord, ‘Fuck you,’ ” that came from real life. You can hear how young everybody was when they were writing these things, but the energy and the attitude was pretty fuckin’ awesome.

Scott Kelly:

I remember seeing Christ on Parade in San Jose, opening up for Social Distortion. The show was fucking amazing. There was so much tension in the room before they even played the first note. They had an intro tape going with news clips interspersed with explosions and all this shit, and they were kind of pacing around. And then they went right into it.

I remember seeing Christ on Parade in San Jose, opening up for Social Distortion. The show was fucking amazing. There was so much tension in the room before they even played the first note. They had an intro tape going with news clips interspersed with explosions and all this shit, and they were kind of pacing around. And then they went right into it.

Martin Sorrondeguy:

I was in Chicago and went to this crazy show at the Cabaret Metro—7 Seconds, Youth of Today, Christ on Parade and Indigesti from Italy. When Youth of Today played, I saw these guys in the pit I had never seen before. They looked super-ultra-punk. They had the spiked, dyed hair and they were in the pit dancing with smiles on their faces, puttin’ their arms around people, pickin’ people up when they fell, just goin’ crazy and enjoying it. I remember thinking, “Who are these guys?” I had never seen anything like that. It was communal. I was used to kids at shows being pretty fuckin’ nasty, and these guys were like into it and havin’ fun. Then, all of a sudden, these kids jump up onstage. “Next up, Christ on Parade from the Bay Area!” It was in that moment I understood somethin’ was different about the Bay Area scene.

I was in Chicago and went to this crazy show at the Cabaret Metro—7 Seconds, Youth of Today, Christ on Parade and Indigesti from Italy. When Youth of Today played, I saw these guys in the pit I had never seen before. They looked super-ultra-punk. They had the spiked, dyed hair and they were in the pit dancing with smiles on their faces, puttin’ their arms around people, pickin’ people up when they fell, just goin’ crazy and enjoying it. I remember thinking, “Who are these guys?” I had never seen anything like that. It was communal. I was used to kids at shows being pretty fuckin’ nasty, and these guys were like into it and havin’ fun. Then, all of a sudden, these kids jump up onstage. “Next up, Christ on Parade from the Bay Area!” It was in that moment I understood somethin’ was different about the Bay Area scene.

Scott Kelly:

The cornerstone of what they could do was their drummer Todd Kramer. He used a ride cymbal like nobody ever has. It would turn everything into this white-noise wash. When the mixture was good, they could just tear a place up. When the mixture was off—somebody was a little too loaded or it was just a bad night—it would just destruct.

The cornerstone of what they could do was their drummer Todd Kramer. He used a ride cymbal like nobody ever has. It would turn everything into this white-noise wash. When the mixture was good, they could just tear a place up. When the mixture was off—somebody was a little too loaded or it was just a bad night—it would just destruct.

Barrie Evans

: I left COP at the start of 1987. It was just a difference of opinion. I got into rockabilly and psychobilly when I was living in Japan. It seemed so different and removed from the already fading punk scene in the U.S. It was nice to be part of a scene that had not yet gotten tainted and regimented. When I got back to the States I wanted to start a band that had the aggression of punk and the melodic structure of rockabilly. The Hellbillys continue to this day.

: I left COP at the start of 1987. It was just a difference of opinion. I got into rockabilly and psychobilly when I was living in Japan. It seemed so different and removed from the already fading punk scene in the U.S. It was nice to be part of a scene that had not yet gotten tainted and regimented. When I got back to the States I wanted to start a band that had the aggression of punk and the melodic structure of rockabilly. The Hellbillys continue to this day.

Noah Landis:

Christ on Parade played all over Europe and the U.K. That trip really blew our minds. A couple of our members decided they actually wanted to move there. When we got back from Europe they said, “I think we’re done.” I was devastated. I felt really proud of all the things we had done. I didn’t want it to break up at all. I still don’t know how and why that fire peters out.

Christ on Parade played all over Europe and the U.K. That trip really blew our minds. A couple of our members decided they actually wanted to move there. When we got back from Europe they said, “I think we’re done.” I was devastated. I felt really proud of all the things we had done. I didn’t want it to break up at all. I still don’t know how and why that fire peters out.

Scott Kelly:

Neurosis practiced in the living room of New Method. I don’t think I left Emeryville for an entire year. I worked in Emeryville, I lived at New Method, and I ate at the liquor store across the street. You didn’t need to go anywhere else. We had our practice space, we had a gig space, we had our dealers, we had the liquor store, we had the food—it was done. It was a place filled with massive, mind-expanding nights, and a lot of really intelligent people were living there, putting out records, starting bands.

Neurosis practiced in the living room of New Method. I don’t think I left Emeryville for an entire year. I worked in Emeryville, I lived at New Method, and I ate at the liquor store across the street. You didn’t need to go anywhere else. We had our practice space, we had a gig space, we had our dealers, we had the liquor store, we had the food—it was done. It was a place filled with massive, mind-expanding nights, and a lot of really intelligent people were living there, putting out records, starting bands.

Jesse Michaels:

Neurosis were my friends but they were just so

rad

, the word I would have used at the time, for having a band. They evolved from other bands like Violent Coercion and SFT, who I worshipped when I was a kid.

Neurosis were my friends but they were just so

rad

, the word I would have used at the time, for having a band. They evolved from other bands like Violent Coercion and SFT, who I worshipped when I was a kid.

Scott Kelly:

I remember being at Ruthie’s when me and Dave and Jason first started conceptualizing our idea. We watched five bands in a row and they all sounded the same. It was that metal-core thing, a couple of longhairs and a couple of guys with mohawks, going back and forth between the chunky riff and the mosh part. We were not gonna do any of that shit.

I remember being at Ruthie’s when me and Dave and Jason first started conceptualizing our idea. We watched five bands in a row and they all sounded the same. It was that metal-core thing, a couple of longhairs and a couple of guys with mohawks, going back and forth between the chunky riff and the mosh part. We were not gonna do any of that shit.

Dave Ed:

Things had been more stylistically open in the early ’80s, even in the thrash and hardcore scene. We were in this quandary. Why should we even have to think about style? We should just play what was coming out of us. So we took some time to think about where this band was going to go.

Things had been more stylistically open in the early ’80s, even in the thrash and hardcore scene. We were in this quandary. Why should we even have to think about style? We should just play what was coming out of us. So we took some time to think about where this band was going to go.

Scott Kelly:

It was basically a two-week conversation between me, Dave and Jason, where we X-ed out everything we didn’t want to do. Then we isolated six bands, saying, “Okay, these are the real deal.” Black Flag—that was a band that didn’t give a fuck. Rudimentary Peni was a deep influence—that really introspective, dark, minor key, creepy stuff. Joy Division, which was just about as pure as it gets. The early Pink Floyd stuff with Syd Barrett and a little bit beyond. Amebix, which was this English Black Sabbath-influenced crustcore band. And everything from the Germs to bands like Voivod. Weird, experimental metal shit. We literally wrote these names on the wall. Our ideas to use visuals, keyboards—all that stuff was all established right at that point.

It was basically a two-week conversation between me, Dave and Jason, where we X-ed out everything we didn’t want to do. Then we isolated six bands, saying, “Okay, these are the real deal.” Black Flag—that was a band that didn’t give a fuck. Rudimentary Peni was a deep influence—that really introspective, dark, minor key, creepy stuff. Joy Division, which was just about as pure as it gets. The early Pink Floyd stuff with Syd Barrett and a little bit beyond. Amebix, which was this English Black Sabbath-influenced crustcore band. And everything from the Germs to bands like Voivod. Weird, experimental metal shit. We literally wrote these names on the wall. Our ideas to use visuals, keyboards—all that stuff was all established right at that point.

Dave Ed:

We came up with a whole plan without even trying. And what we came to was, let’s make this the band that we’re going to be in for the rest of our lives.

We came up with a whole plan without even trying. And what we came to was, let’s make this the band that we’re going to be in for the rest of our lives.

Scott Kelly:

We would do this until we were dead. And that remains the commitment. We will go until one or all of us is gone. And that will be the end of it. We were completely obsessed with leaving a mark. And also submitting ourselves to music, and letting music become us.

We would do this until we were dead. And that remains the commitment. We will go until one or all of us is gone. And that will be the end of it. We were completely obsessed with leaving a mark. And also submitting ourselves to music, and letting music become us.

Dave Ed:

I was about 16 when we started Neurosis.

I was about 16 when we started Neurosis.

Scott Kelly:

I was possibly 18. Jason was 15.

I was possibly 18. Jason was 15.

Martin Brohm:

Dave Ed’s dad taught drafting in a math class in El Sobrante. He was a funny guy. He walked in one day and threw a cassette tape at me. It bounced off my head, landed on my desk. He said, “My son does this crap. It sounds like hell, but you might like it.” It was the old Neurosis demo tape.

Dave Ed’s dad taught drafting in a math class in El Sobrante. He was a funny guy. He walked in one day and threw a cassette tape at me. It bounced off my head, landed on my desk. He said, “My son does this crap. It sounds like hell, but you might like it.” It was the old Neurosis demo tape.

Noah Landis:

I saw the very first Neurosis show back in 1986. I think Victim’s Family played.

I saw the very first Neurosis show back in 1986. I think Victim’s Family played.

Sham Saenz:

Man, the early days, the first shows. Neurosis was always a good band. Dave is a fuckin’ amazing bass player. They got Steve Von Till in the band, and it was like the perfect key that they needed.

Man, the early days, the first shows. Neurosis was always a good band. Dave is a fuckin’ amazing bass player. They got Steve Von Till in the band, and it was like the perfect key that they needed.

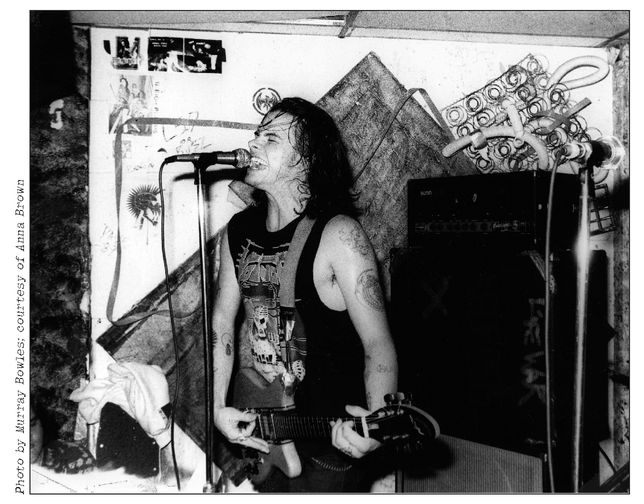

The Word as Law: Scott Kelly from Neurosis

Kate Knox:

Early Neurosis shows were absolutely amazing.

Early Neurosis shows were absolutely amazing.

Anna Brown:

People were writhing around on the floor. Not in like a Crash Worship-hippie kind of way, but in a “I can’t contain myself this is so exciting!” kind of way. They had 20 totally epic songs that they would play, and people would just go fuckin’ crazy. They played a lot, too. They were sort of an anchor.

People were writhing around on the floor. Not in like a Crash Worship-hippie kind of way, but in a “I can’t contain myself this is so exciting!” kind of way. They had 20 totally epic songs that they would play, and people would just go fuckin’ crazy. They played a lot, too. They were sort of an anchor.

Billie Joe Armstrong

: There was an entire scene of people around them—this Oakland punk rock scene that included them and Christ on Parade. Neurosis were really scary.

: There was an entire scene of people around them—this Oakland punk rock scene that included them and Christ on Parade. Neurosis were really scary.

Noah Landis:

Scott and Dave both sang. Dave has within him the ultimate Cookie Monster voice. I don’t know where it comes from. And Scott has a real intensity in his soul. Everything that comes out of him is real. He is not trying to do anything, it’s just what is inside of him getting out.

Scott and Dave both sang. Dave has within him the ultimate Cookie Monster voice. I don’t know where it comes from. And Scott has a real intensity in his soul. Everything that comes out of him is real. He is not trying to do anything, it’s just what is inside of him getting out.

Billie Joe Armstrong:

One night Scott Kelly had a brand-new baby, and the mother and the baby were sitting onstage and the crowd was just going berserk. Someone did a stage dive and nearly kicked the baby. It was a brand-new baby, I don’t even think it was six months old. Scott just lost it. He jumped into the crowd and just started beating this guy. Then he jumped back onstage and said, “That’s my baby, man!” I remember thinking, there is a new life here. It was art and punk and children. There were kids from the suburbs, kids from Berkeley, and these old ex-hippie, Vietnam-era guys—all percolating in the same spot.

One night Scott Kelly had a brand-new baby, and the mother and the baby were sitting onstage and the crowd was just going berserk. Someone did a stage dive and nearly kicked the baby. It was a brand-new baby, I don’t even think it was six months old. Scott just lost it. He jumped into the crowd and just started beating this guy. Then he jumped back onstage and said, “That’s my baby, man!” I remember thinking, there is a new life here. It was art and punk and children. There were kids from the suburbs, kids from Berkeley, and these old ex-hippie, Vietnam-era guys—all percolating in the same spot.

Adrienne Droogas:

You’d get so swept up in the music and all the punks would be singing every single song. Before I was singing in Spitboy, I came up to Scott and said, “Hey, do you mind if I get up and sing part of ‘Blister’ with you?” And he said, “You see that microphone over there? That’s your microphone whenever you want.” I was all nervous but they started playing the song and I jumped up and started singing along, and then Noah from Christ on Parade jumped up and he started singing along, and then we did stage dives. They were just an awesome band.

You’d get so swept up in the music and all the punks would be singing every single song. Before I was singing in Spitboy, I came up to Scott and said, “Hey, do you mind if I get up and sing part of ‘Blister’ with you?” And he said, “You see that microphone over there? That’s your microphone whenever you want.” I was all nervous but they started playing the song and I jumped up and started singing along, and then Noah from Christ on Parade jumped up and he started singing along, and then we did stage dives. They were just an awesome band.

Other books

Bittersweet by Peter Macinnis

Modern Serpents Talk Things Through by Jamie Brindle

Uglies by Scott Westerfeld

Chasing the Witch (Boston Witches) by Gibson, Jessica

Desperate Domination (Bought by the Billionaire #3) by Lili Valente

The Secret Chicken Society by Judy Cox

Coffee Scoop by Kathleen Y'Barbo

The Bondwoman's Narrative by Hannah Crafts

SevenMarkPackAttackMobi by Weldon, Carys

Splendors and Glooms by Laura Amy Schlitz