Ghost Girl (35 page)

‘Shame woodlice can’t talk. They could tell us what happened here,’ Stella remarked more to herself than Jack. Sheltering under the spreading branches she shone her torch on to the folder and prised apart the damp pages. Water had penetrated the plastic files. She couldn’t risk damage. She hurried back to the van and laid the folder on the passenger seat.

As Jack had supposed, the photographs referenced ‘2’ and ‘2a’ matched Mafeking Avenue. The tree was in the second of two shots. Terry had shot it in the winter when the branches were bare and stark; now it was lush with green leaves. The apartment block was in the picture; despite what Jack had said earlier, Terry had known it was there. She looked again. It was a shell. A defunct warehouse with gaping holes for delivery of goods. These were picture windows done up with fancy balconies. The slogan ‘George Davis Is Innocent’ was sprayed across the bricks.

‘I assumed that Terry compiled this collection over a short period of time.’ Jack opened the passenger door. ‘But I’d say his suspicions were aroused years ago. No one was living in here when our fatal accident took place.’

Stella got out her grid. Meticulously she wrote in Mafeking Avenue and Terry’s photo references. Maybe Jack was right. She did like to collect and quantify.

‘They live about two years, although some have made it to four,’ Jack got in. ‘The woodlice witnesses to the crash were ancestors of these ones. Judging by the age of the scar, it’s like the ice age for us.’

‘The killer might return to the scene of the crime. He could be here now.’ Stella checked her mirrors. Although the street was quiet, he could be out there. She could see a salt bin a few metres away: a good hiding place.

‘I doubt it. He takes no chances. He’s a collector. He’s concerned with increasing his collection, not with playing cat and mouse with the police.’

‘He went back to Marquis Way. That was a risk. He wouldn’t know the police don’t analyse traffic collisions and that someone had not spotted a pattern.’

‘Terry did.’ Jack scrutinized the stones in the bag. ‘Maybe you should talk to your new friend.’

‘Meaning?’ Stella started the engine. She knew what he meant.

‘She’ll know her way around their systems. Not much she can’t find out. Bet she eats and sleeps her job. You said she instantly recalled the facts about Tolworth Street. She gave you flowers; she might want to help.’

‘It’s Terry she wanted to help.’ Marian would not have bothered with her if she were not Terry Darnell’s daughter. ‘A moment ago you wanted this to be our secret.’

‘Don’t say why you’re asking.’

‘Marian’s not stupid.’ Marian was law-abiding and hard-working and Stella respected that. She would not ask her to bend the rules. Jack’s concept of right and wrong was hazy. Although recently her own morality had been up for grabs. She had not yet found a way to return the green form. She did not say that unwittingly Marian had already helped them. Stella put ‘Tolworth Street’ into the satnav.

‘After three hundred yards turn left.’

‘So far we know at least three men died on desolate streets at night and the green glass leads us to be sure they were murdered. The killer marked the sites with seven green chips of glass.’ She tilted her head; a car behind them had its headlights on full beam, the light bright in the wing and rear mirrors. ‘We don’t know why and we don’t know how.’ Stella accelerated.

‘Slow down or we’ll have a crash.’ Jack was gripping the handle fixed above the door frame.

‘There’s nothing coming.’ A train driver, he must be used to being in control.

‘If someone stepped off the kerb, you’d have nowhere to go.’

Stella braked. Jack screamed.

‘That’s it!’ She cut the engine. ‘He stepped out and they swerved and smashed into the trunks. No cameras, no pedestrians; no witnesses. He walked away. The events put down as tragic accidents. No one noticed that the dead drivers had all run over children. No one saw the bigger picture.’

Jack grabbed her arm. ‘Brilliant, Stella!’

‘Although how could he be certain they’d take avoidance action? Some people are slow to react.’

‘A potential flaw. I suspect he courts the risk. Like Russian roulette. Later he returns and buries the glass. Job done.’

‘Or he buries the pieces before the event. A marker, a promise to himself.’

‘Nice one. That’s thinking like me!’ Jack rattled the glass. ‘Although the forensics crawling all over the scene might have found them. A risk too far.’

‘Must have been afterwards. No one would draw any significance from the stones. Even though they are at every crash site.’ Stella started the van and pulled out. ‘No one analyses the data. Besides, as we know, they were not found.’

‘He executed the perfect murder over and over again.’ Jack put the stones in his coat pocket with the others.

‘He’s pure evil.’ Stella checked her mirror. No cars now. The street was dark.

‘No such thing as evil. It’s the deed, not the person who is evil.’

‘If you commit evil you are evil. Wait a moment.’ Stella slowed the van, but didn’t brake this time. ‘I know what it is.’

‘What what is?’

‘The glass. It’s aggregate, the jade variety. David used it to decorate his wife’s grave. It saves weeding.’

‘You have reached your destination.’

Sunday, 3 July 1966

Her mum and dad were in bed, but she could not be sure they were asleep so was extra specially careful. She had her clothes on over her pyjamas and her anorak over her jumper. This made it hard to walk, but she would be warm.

After tea, when her mum was in bed and her dad was in Michael’s room (even though it was empty), Mary had packed provisions for her expedition. Torch, her dad’s trowel, some Fruit Salad chews and a ball of string. The last had no direct use, but she had read somewhere that it always came in handy. She was disappointed Michael wasn’t there to see, but if he were he would only give her away.

Don’t forget the key.

She snatched the key off the hook in the hall.

I’m scared.

Shut up. She cycled down British Grove, head down. The duffel bag was heavier than she had expected. She knew the way without a map. The task was not for scaredy cats, she informed Michael. She had a stitch in her side and despite the biting night air she was hot. She leant her bike against the wall and squeezed through the break in the cemetery railings.

Mary Thornton had not known that in the city it was never dark and found she could see without her torch. The path was a pale line between the graves. She didn’t like being so close to dead people; she had made her plan in the sunshine.

The Angel was taller than ever. Mary felt afraid. She would not let Michael see. If he was watching over her like the vicar said, he knew anyway.

She battled through a bush of ground elder, her duffel bag an impediment, and then did a lopsided crawl to a clearing in the middle. She laid down the bag and scrabbled furiously at the earth with her trowel. She dug a hole a foot deep and about eighteen inches in circumference and lowered the bag down.

‘Dust thou art, and unto dust thou shalt return

.’

She clawed at the soil until the bag was covered and then made good the disturbance with a scattering of dried pine needles and leaves. She shoved her way out, splintering and snapping branches, careless of discovery.

The Angel watched the little girl tear up and down maze-like paths until she found the gap in the railings.

Wednesday, 2 May 2012

Stella tipped the lever enough to reel the film to fit the screen. She was back in the Hammersmith and Fulham Archives. That morning she had cancelled the rearranged recruitment meeting with Jackie to come to the library. She would do what Terry called good old-fashioned legwork. She had put into the grid the street names Jack had sung to the tune of the nursery rhyme. This had seemed real progress, until the internet failed to throw up an incident for Mafeking Avenue or another one for Marquis Way, apart from Vickery. They could have been wrong about the telegraph pole; it might have been pranged innocently. Then she remembered they had found bits of jade glass there. More frustrating was that she could find nothing for Tolworth Street where Marian said a man called David Lauren had died in 1989. The web wouldn’t deliver the Holy Grail.

Last night, when they had gone to Tolworth Street, they had located a scarred beech tree. Jade glass beneath its roots confirmed this was where Lauren had died. Jack was impressed with the tree for surviving the 1987 hurricane and the impact of Lauren’s car. He had told it so.

They had a year and a name for number four in Terry’s series of seven. There was no tree on Spelling Way, another street in Jack’s song. He had been vague about why he had included it. Stella wouldn’t put it past him to like how it fitted in the tune. She would discount it for now as they had enough to go on.

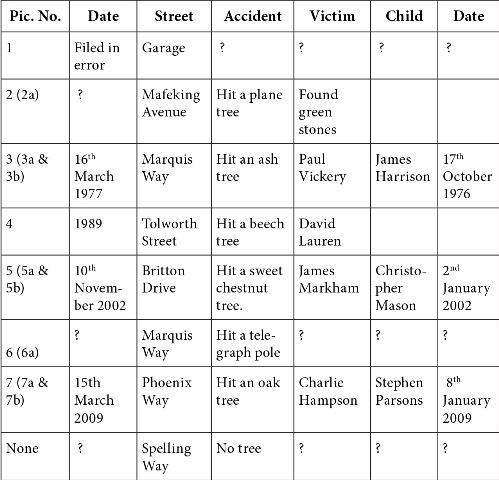

She opened her Filofax at her grid and took out papers she had stuffed in there. One caught her eye and she smoothed it out. It was the article about James Markham’s death she had printed up the last time she was here. She was about to refold it when a name caught her eye. Christopher Mason. Markham had killed a boy in the January before his own death in November 2002. At the time she had thought little of it. Three dead children was definitely a trend. Green stones at the base of the pole were the only proof something else had happened on Marquis Way apart from Vickery’s death. She had the bare details in row six and amended Vickery’s accident column to specify the type of tree. Terry would say it was important. They now knew the date of Charles Hampson’s death; she filled it in. Although there was a photograph for Mafeking Avenue, again green stones were all they had to indicate an event had happened there. Stella folded her arms and looked at the grid. They had street names for all the photographs except for number one, of the garage mechanic under the car which might not belong in the file.

She tried to think what Terry’s approach would be and returned a blank. She would use her method of scoping a job. She calculated the square footage, identified specific issues, like stains on a carpet. She broke these down to the kind of stains and length of time they had been there. Step by step. Stain by stain.

The first step was to establish when the warehouse in Mafeking Avenue was converted into apartments. Stella sat up. There had been a plaque on the wall. She tried to picture it, but did not have Jack’s photographic memory. He might remember; it was an excuse to call and gauge his mood around David Barlow. No, no point. He had not looked at the plaque.

Stella grabbed her iPhone and brought up Street View. Seconds later she had up Mafeking Avenue on a sunny day. She swivelled the handset to landscape. There was the plane tree. She found she was looking for Jack’s woodlice. Concentrate! A few more metres and she was outside the supermarket. She rotated ninety degrees to face the apartment block. The plaque was a fuzzy square behind the railings. Involuntarily she jerked her head to see around them. Zooming in did not help; she couldn’t read the inscription. She was about to give up when it sprang into focus.

Th foundation one was lai y

Counc r Vince Har wick

6 ne 01

Two black stripes – the railings – cut out letters but she had enough to go on. Only one month ended with: ‘ne’. June. The year had to be 2001. The building wasn’t flats when Terry took the picture. It was a lead, a slim one, but a lead none the less.

Stella found the film for 2001 and fed it into the machine. She skimmed at breakneck speed to June. The sixth had been a Wednesday that year. The

Chronicle

was published on Thursdays. She inched along to 7 June and found her grail.

COUNCILLOR FIRES THE STARTING GUN

By Lucille May

Vince Hardwick, Chair of the council, unveiled a plaque for Wilton Retreat, the conversion of the Wilton flour warehouse into luxury apartments yesterday. This kicks off the regeneration plan for Mafeking Avenue. The warehouse, operational for a century, was mothballed in 1963 when flour-production methods changed and bakers didn’t need to sift flour. Hardwick used his casting vote to veto a campaign by local residents for a housing association development for low-income families. The apartments, perfect for those with telephone number salaries, include a penthouse and offer spectacular views over West London.

We reminded Mr Hardwick that in 1970 Denis Atkins, who had held his position at the council, died when his MG Midget hit the tree that still stands opposite the warehouse. Appearing flustered he assured us the flats were a fitting monument.

Molly Atkins, 73, who lays flowers by the tree every year, insisted that her husband would not approve of ordinary people being deprived of a home.

If only the clumsy mechanism offered a search facility. With fifty-two weeks of 1970 to trawl though, this truly was legwork. An hour later Stella was rewarded. According to the nightwatchman at the nearby empty flour warehouse, Denis Atkins died on Monday, 7 September, around about eleven-thirty. Lucille May reported his death in four lines in that Thursday’s

Chronicle

. Persisting, Stella found another article by May, who had gone to his inquest two weeks later. Despite recent storms, Monday had been dry; there had been no black ice. Atkins had no alcohol in his blood and his Midget was in good repair. The verdict was ‘Accidental Death’. She hit ‘print’ and put the dead councillor in her grid.