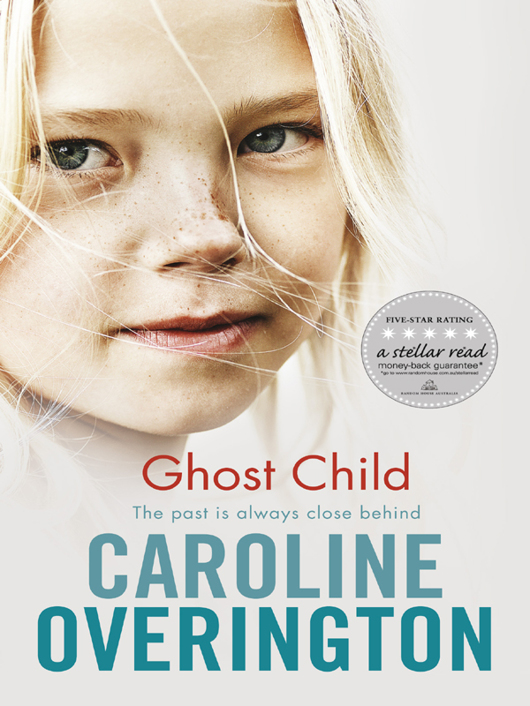

Ghost Child

Authors: Caroline Overington

Also by Caroline Overington

Fiction

I Came to Say Goodbye

Non Fiction

Only in New York

Kickback

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian

Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Ghost Child

ePub ISBN 9781864714562

Kindle ISBN 9781864717112

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

A Bantam book

Published by Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Highway, North Sydney NSW 2060

www.randomhouse.com.au

First published by Bantam in 2009

This edition published in 2010

Copyright © Caroline Overington 2009

Lyrics from ‘You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go’ by Bob Dylan © Ram’s Horse Music, 1974

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian

Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia.

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at

www.randomhouse.com.au/offices

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

Overington, Caroline.

Ghost child.

ISBN 978 1 86471 109 7 (pbk).

Homicide – Victoria – Fiction.

A823.4

Cover photograph by David Trood, courtesy of Getty Images

Cover design by Christabella Designs

For Katie

I see you in the sky above

In the tall grass

In the ones I love

Bob Dylan

On 11 November 1982, Victorian police were called to a home on the Barrett housing estate, an hour west of Melbourne. In the lounge room of an otherwise ordinary brick-veneer home, they found a five-year-old boy lying still and silent on the carpet. His arms were by his sides, his palms flat.

There were no obvious signs of trauma. The boy was neither bruised nor bleeding, but when paramedics turned him gently onto his side they found an almost imperceptible indentation in his skull, as broad as a man’s hand and as shallow as a soap dish.

The boy’s mother told police her son had been walking through the schoolyard with one of his younger brothers when they were approached by a man who wanted the change in their pockets. The brothers refused

to hand over the money so the man knocked the older boy to the ground and began to kick and punch him.

The younger boy ran home to raise the alarm. Their mother carried the injured boy home in her arms. She called an ambulance, but nothing could be done.

The story made the front page of

The Sun

newspaper in Melbourne and the TV news.

Police made a public appeal for witnesses but, in truth, nobody really believed the mother’s version of events. The Barrett Estate was poor but no one was bashing children for loose change – not then. Ultimately, the mother and her boyfriend were called in for questioning. Police believed that one of them – possibly both – was involved in the boy’s death.

There was a great deal of interest in the case, but when it finally came to court, the Chief Justice closed the hearing. The verdict would be released; so, too, would any sentence that was handed down. But the events leading up to the little boy’s death would remain a mystery.

Few people were surprised to hear that the boy’s mother and her boyfriend went to prison for the crime. Police declared themselves satisfied with the result, saying there was no doubt justice had been done. And yet for years rumours swept the Barrett Estate, passing from neighbour to neighbour and clinging like cobwebs to the long-vacant house: there had been a cover-up. The real perpetrator, at least according to local gossip, was the boy’s six-year-old sister, Lauren.

When a young woman lives by herself, it’s assumed she must be lonely. I’d say the opposite is true. In fact, if anybody had asked me what it was like when I first started living on my own, I would have said, ‘It was perfect.’ I was completely alone – I had no close friends, and nobody I called family – and that was precisely what I wanted.

The place I moved into was basically a shed, and it was built on a battle-axe block behind somebody else’s house. The property itself was on Sydney’s northern beaches. There was a family living in the main house, the one that fronted the beach. They owned the block and, like many Sydneysiders who had beachside property in the 1980s, they decided to make the most of it by carving a driveway down the side, building a granny flat out the back and renting it to me.

After the first meeting, when they gave me the keys and we talked about the rent, I had nothing whatsoever to do with them. They were a family – a mum, a dad and two teenage kids – living in the main house, and I was the boarder. I could get to my place without bothering them. I just walked down the driveway, opened my door and I was home. I had my own toilet, shower and enough of a kitchen, so there was no reason to go knocking.

Before I moved in, I bought four things. The most expensive was a queen-size sheet set in a leopard-skin print, with two pillowcases. I bought a box of black crockery, with dinner plates shaped like hexagons. I had this idea, then, that I might one day have close friends who could come over for dinner. I also bought a new steam iron and ironing-board, these last things because it was a condition of my employment that my uniform be straight and clean.

I still remember the first morning I woke in my own place. I was seventeen years old. I padded into the kitchen in my moccasins, put the kettle on the stove top, and pressed the red button to make the flame ignite. I took the plastic cover off the new ironing-board and scrunched it into a ball. I was fiddling underneath the board, trying to find the lever that makes the legs stick out, when the kettle began to whistle itself into hysterics. I put the ironing-board down and took a cup from the crockery set, removing some of the cardboard that

had been packed around it, and made a cup of tea – hot and sugary, with the bag taken out, not left in – and I thought to myself, ‘This is just like playing house! I’m okay here. Things are going to be fine.’

When the family told the neighbours they’d rented out the granny flat, they probably wanted to know whether I was going to cause trouble – whether I was going to bring boys home and make a racket. But the answer was no, I was not. I amused myself in the granny flat by learning new and humble domestic tasks: sweeping the floor with a straw broom; bending to collect the mess in a dustpan and brush; buying garbage bags with two handles that tied at the top. My idea of a good night was to eat Tim Tams in bed and to smoke cigarettes on the porch, although only after I saw the lights in the main house go out.

The owners would have said, ‘Oh, she’s the perfect tenant, like a mouse, so quiet, you never even know she’s there.’

From time to time, I’d bump into the mum – not my mum, but the mum who lived in the main house. I’d be heading out to work and she’d be on the nature strip, getting shopping bags out of the boot of her car or something, and she’d smile at me – probably because everybody approves of hospital staff – and I’d smile back at her.

I didn’t see much of the dad. Perhaps he’d decided that there was nothing to be gained from getting too

close to the girl who lived in his shed. I had nothing much to do with the children, either. I was closer in age to them than to their parents, but really, what did we have in common? They came out from time to time, to jump on the trampoline and to sit under the pirate flag in the old tree house, but we rarely spoke.

I’d taken a job as a nurse’s aide in a city hospital, and I’m sure my co-workers at first understood why I lived alone. I was new to Sydney so it made sense, at least in the beginning, that I wouldn’t have many friends. After I’d settled, though, they must have wondered why I continued to live in a granny flat when I could easily have shared a city apartment with one of the other aides. The noticeboard at work often had handwritten signs tacked up, advertising rooms for rent. ‘Outgoing girl wanted to share FUN FLAT!’ one of the ads said. The truth is, the things the other girls wanted to do – going to nightclubs, drinking Fluffy Ducks and Orgasms and Harvey Wallbangers – didn’t sound like fun to me.

Of course, I wasn’t famous then, far from it. I was just the quiet girl, the churchy girl that lived alone, prayed in the hospital chapel, and never socialised. I’m sure they all got a shock when photographs of me started appearing in newspapers, just as I’m sure the family I boarded with got a shock when journalists swarmed the granny flat, waving microphones on sticks.

I got a bit of a shock myself. I took refuge in my bed, hiding under the leopard-skin sheets, trying to fight

the urge to

run

. Because, really, run where? There was nowhere to go.

I don’t know how long I would have stayed under the covers if Harley hadn’t turned up. He walked down the side drive, past the windows of the main house. I heard the mum rap on the glass. ‘Hey, you,’ she said. ‘Off our property!’

Harley said, ‘I’m not with the media. I’m Harley Cashman. Lauren’s my sister.’

She would have been startled. For one thing, the mum knew me not as Lauren Cashman but as Lauren

Cameron,

which was the name I’d given her when I moved in. She didn’t know I had a brother, either. I’d told them what I used to tell everyone: ‘I have no family.’

Harley knocked at my door and when I didn’t answer, I heard him push it open. I didn’t stir but I could feel warm sunshine pour across my bed.

Harley said, ‘Mate, what

are

you doing? Everyone’s looking for you.’

I didn’t respond so he pulled back the doona and said, ‘Lauren, seriously, this is ridiculous. Get up.’

I felt so frightened and overwhelmed that I wasn’t sure that I could. I said to Harley, ‘I can’t.’

He said, ‘Sure you can.’

We went on like that for a while, him saying, ‘Come on, Lauren,’ and me saying, ‘Just go away, Harley,’ until he said, ‘Okay, look, I’m not going to hang around here forever. If you want me gone, I’m gone.’

It was then that I realised I didn’t want him to go, not without me, not ever again. I rose from the bed, untangling myself from the sheets, and said, ‘Okay, all right.’

‘That’s right,’ he said. ‘Get up, and let’s get you out of here.’

I was wearing only a T-shirt and a pair of knickers.

‘You’re going to need to get dressed,’ he said, and started picking up some clothes I’d flung onto the floor. Compared with him – with anyone – I was tiny. He held up a pair of my pants and said, ‘How do you even get one leg in here?’

I snatched them away and went into the bathroom to dress myself.

‘Good on you,’ he said when I emerged. ‘Now, let’s go.’

He ushered me to the door and we left the granny flat together, me with a jumper over my head in case there was a photographer still lurking, trying to get a picture. He’d parked his car on the nature strip. I couldn’t see anything because the jumper was over my face so he guided me into the passenger seat. It was only once we’d started moving, once I was sure we were clear of the suburban streets and onto a freeway, that I took the jumper off, and said, ‘Where are we going?’

Harley said, ‘I’ve decided that you should meet the folks.’

I said, ‘

Whose

folks?’

He said, ‘Mum is gonna love you.’

I thought, ‘

Your

mum. Not mine.’

I rolled the jumper into a ball and put it on the floor near my feet. I said, ‘She doesn’t even

know

me, Harley.’

He said, ‘Mate, you’re my

sister

. What more is there to know?’

I didn’t answer. What more was there to know? What do any of us know? We think we know the basic facts about our lives: those are my parents and these are my siblings and this is my story, at least as I’ve come to tell it. But, really, how much of it is true?