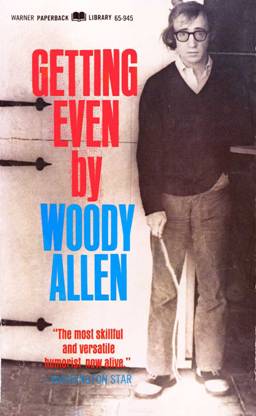

Getting Even

Authors: Woody Allen

Annotation

After three decades of prodigious film work (and some unfortunate tabloid adventures as well), it's easy to forget that Woody Allen began his career as one heck of a great comedy writer. Getting Even, a collection of his late '60s magazine pieces, offers a look into Allen's bag of shtick, back when it was new. From the supposed memoirs of Hitler's barber: "Then, in January of 1945, a plot by several generals to shave Hitler's moustache in his sleep failed when von Stauffenberg, in the darkness of Hitler's bedroom, shaved off one of the Führer's eyebrows instead…"

Even though the idea of writing jokes about old Adolf-or addled rabbis, or Maatjes herring-isn't nearly as fresh as it used to be, Getting Even still delivers plenty of laughs. At his best, Woody can achieve a level of transcendent craziness that no other writer can match. If you're looking for a book to dip into at random, or a gift for someone who's seen Sleeper 13 times, Getting Even is a dead lock.

Getting Even

Venal amp; Sons has at last published the long-awaited first volume of Metterling’s laundry lists

(The Collected Laundry Lists of Hans Metterling,

Vol. I, 437 pp., plus XXXII-page introduction; indexed; $18.75), with an erudite commentary by the noted Metterling scholar Gunther Eisenbud. The decision to publish this work separately, before the completion of the immense four-volume a

euvre,

is both welcome and intelligent, for this obdurate and sparkling book will instantly lay to rest the unpleasant rumors that Venal amp; Sons, having reaped rich rewards from the Metterling novels, play, and notebooks, diaries, and letters, was merely in search of continued profits from the same lode. How wrong the whisperers have been! Indeed, the very first Metterling laundry list

List No. 1

6 prs. shorts

4 undershirts

6 prs. blue socks

4 blue shirts

2 white shirts

6 handkerchiefs

No Starch

serves as a perfect, near-total introduction to this troubled genius, known to his contemporaries as the “Prague Weirdo.” The list was dashed off while Metterling was writing

Confessions of a Monstrous Cheese,

that work of stunning philosophical import in which he proved not only that Kant was wrong about the universe but that he never picked up a check. Metterling’s dislike of starch is typical of the period, and when this particular bundle came back too stiff Metterling became moody and depressed. His landlady, Frau Weiser, reported to friends that “Herr Metterling keeps to his room for days, weeping over the fact that they have starched his shorts.” Of course, Breuer has already pointed out the relation between stiff underwear and Metterling’s constant feeling that he was being whispered about by men with jowls

(Metterling: Paranoid-Depressive Psychosis and the Early Lists,

Zeiss Press). This theme of a failure to follow instructions appears in Metterling’s only play,

Asthma,

when Needleman brings the cursed tennis ball to Valhalla by mistake.

The obvious enigma of the second list

List No. 2

7 prs. shorts

5 undershirts

7 prs. black socks

6 blue shirts

6 handkerchiefs

No Starch

is the seven pairs of black socks, since it has been long known that Metterling was deeply fond of blue. Indeed, for years the mention of any other color would send him into a rage, and he once pushed Rilke down into some honey because the poet said he preferred brown-eyed women. According to Anna Freud (“Metterling’s Socks as an Expression of the Phallic Mother,”

Journal of Psychoanalysis,

Nov., 1935), his sudden shift to the more sombre legwear is related to his unhappiness over the “Bayreuth Incident.” It was there, during the first act of

Tristan,

that he sneezed, blowing the toupee off one of the opera’s wealthiest patrons. The audience became convulsed, but Wagner defended him with his now classic remark “Everybody sneezes.” At this, Cosima Wagner burst into tears and accused Metterling of sabotaging her husband’s work.

That Metterling had designs on Cosima Wagner is undoubtedly true, and we know he took her hand once in Leipzig and again, four years later, in the Ruhr Valley. In Danzig, he referred to her tibia obliquely during a rainstorm, and she thought it best not to see him again. Returning to his home in a state of exhaustion, Metterling wrote

Thoughts of a Chicken,

and dedicated the original manuscript to the Wagners. When they used it to prop up the short leg of a kitchen table, Metterling became sullen and switched to dark socks. His housekeeper pleaded with him to retain his beloved blue or at least to try brown, but Metterling cursed her, saying, “Slut! And why not Argyles, eh?”

In the third list

List No. 3

6 handkerchiefs

5 undershirts

8 prs. socks

3 bedsheets

2 pillowcases

linens are mentioned for the first time: Metterling had a great fondness for linens, particularly pillowcases, which he and his sister, as children, used to put over their heads while playing ghosts, until one day he fell into a rock quarry. Metterling liked to sleep on fresh linen, and so do his fictional creations. Horst Wasserman, the impotent locksmith in

Filet of Herring,

kills for a change of sheets, and Jenny, in

The Shepherd’s Finger,

is willing to go to bed with Klineman (whom she hates for rubbing butter on her mother) “if it means lying between soft sheets.” It is a tragedy that the laundry never did the linens to Metterling’s satisfaction, but to contend, as Pfaltz has done, that his consternation over it prevented him from finishing

Whither Thou Goest, Cretin

is absurd. Metterling enjoyed the luxury of sending his sheets out, but he was not dependent on it.

What prevented Metterling from finishing his long-planned book of poetry was an abortive romance, which figures in the “Famous Fourth” list:

List No. 4

7 prs. shorts

6 handkerchiefs

6 undershirts

7 prs. black socks

No Starch

Special One-Day Service

In 1884, Metterling met Lou Andreas-Salome, and suddenly, we learn, he required that his laundry be done fresh daily. Actually, the two were introduced by Nietzsche, who told Lou that Metterling was either a genius or an idiot and to see if she could guess which. At that time, the special one-day service was becoming quite popular on the Continent, particularly with intellectuals, and the innovation was welcomed by Metterling. For one thing, it was prompt, and Metterling loved promptness. He was always showing up for appointments early-sometimes several days early, so that he would have to be put up in a guest room. Lou also loved fresh shipments of laundry every day. She was like a little child in her joy, often taking Metterling for walks in the woods and there unwrapping the latest bundle. She loved his undershirts and handkerchiefs, but most of all she worshipped his shorts. She wrote Nietzsche that Metterling’s shorts were the most sublime thing she had ever encountered, including

Thus Spake Zarathustra.

Nietzsche acted like a gentleman about it, but he was always jealous of Metterling’s underwear and told close friends he found it “Hegelian in the extreme.” Lou Salome and Metterling parted company after the Great Treacle Famine of 1886, and while Metterling forgave Lou, she always said of him that “his mind had hospital corners.”

The fifth list

List No. 5

6 undershirts

6 shorts

6 handkerchiefs

has always puzzled scholars, principally because of the total absence of socks. (Indeed, Thomas Mann, writing years later, became so engrossed with the problem he wrote an entire play about it,

The Hosiery of Moses,

which he accidentally dropped down a grating.) Why did this literary giant suddenly strike socks from his weekly list? Not, as some scholars say, as a sign of his oncoming madness, although Metterling had by now adopted certain odd behavior traits. For one thing, he believed that he was either being followed or was following somebody. He told close friends of a government plot to steal his chin, and once, on holiday in Jena, he could not say anything but the word “eggplant” for four straight days. Still, these seizures were sporadic and do not account for the missing socks. Nor does his emulation of Kafka, who for a brief period of his life stopped wearing socks, out of guilt. But Eisenbud assures us that Metterling continued to wear socks. He merely stopped sending them to the laundry! And why? Because at this time in his life he acquired a new housekeeper, Frau Milner, who consented to do his socks by hand-a gesture that so moved Metterling that he left the woman his entire fortune, which consisted of a black hat and some tobacco. She also appears as Hilda in his comic allegory,

Mother Brandt’s Ichor.

Obviously, Metterling’s personality had begun to fragment by 1894, if we can deduce anything from the sixth list:

List No. 6

25 handkerchiefs

1 undershirt

5 shorts

1 sock

and it is not surprising to learn that it was at this time he entered analysis with Freud. He had met Freud years before in Vienna, when they both attended a production of

Oedipus,

from which Freud had to be carried out in a cold sweat. Their sessions were stormy, if we are to believe Freud’s notes, and Metterling was hostile. He once threatened to starch Freud’s beard and often said he reminded him of his laundryman. Gradually, Metterling’s unusual relationship with his father came out. (Students of Metterling are already familiar with his father, a petty official who would frequently ridicule Metterling by comparing him to a wurst.) Freud writes of a key dream Metterling described to him:

I am at a dinner party with some friends when suddenly a man walks in with a bowl of soup on a leash. He accuses my underwear of treason, and when a lady defends me her forehead falls off. I find this amusing in the dream, and laugh. Soon everyone is laughing except my laundryman, who seems stern and sits there putting porridge in his ears. My father enters, grabs the lady’s forehead, and runs away with it. He races to a public square, yelling, “At last! At last! A forehead of my own! Now I won’t have to rely on that stupid son of mine.” This depresses me in the dream, and I am seized with an urge to kiss the Burgomaster’s laundry. (Here the patient weeps and forgets the remainder of the dream.)

With insights gained from this dream, Freud was able to help Metterling, and the two became quite friendly outside of analysis, although Freud would never let Metterling get behind him.

In Volume II, it has been announced, Eisenbud will take up Lists 7-25, including the years of Metterling’s “private laundress” and the pathetic misunderstanding with the Chinese on the corner.

It is no secret that organized crime in America takes in over forty billion dollars a year. This is quite a profitable sum, especially when one considers that the Mafia spends very little for office supplies. Reliable sources indicate that the Cosa Nostra laid out no more than six thousand dollars last year for personalized stationery, and even less for staples. Furthermore, they have one secretary who does all the typing, and only three small rooms for headquarters, which they share with the Fred Persky Dance Studio.

Last year, organized crime was directly responsible for more than one hundred murders, and

mafiosi

participated indirectly in several hundred more, either by lending the killers carfare or by holding their coats. Other illicit activities engaged in by Cosa Nostra members included gambling, narcotics, prostitution, hijacking, loansharking, and the transportation of a large whitefish across the state line for immoral purposes. The tentacles of this corrupt empire even reach into the government itself.

Only a few months ago, two gang lords under federal indictment spent the night at the White House, and the President slept on the sofa.

History of Organized Crime in the United States

In 1921, Thomas (The Butcher) Covello and Ciro (The Tailor) Santucci attempted to organize disparate ethnic groups of the underworld and thus take over Chicago. This was foiled when Albert (The Logical Positivist) Corillo assassinated Kid Lipsky by locking him in a closet and sucking all the air out through a straw. Lipsky’s brother Mendy (alias Mendy Lewis, alias Mendy Larsen, alias Mendy Alias) avenged Lipsky’s murder by abducting Santucci’s brother Gaetano (also known as Little Tony, or Rabbi Henry Sharpstein) and returning him several weeks later in twenty-seven separate mason jars. This signalled the beginning of a bloodbath.

Dominick (The Herpetologist) Mione shot Lucky Lorenzo (so nicknamed when a bomb that went off in his hat failed to kill him) outside a bar in Chicago. In return, Corillo and his men traced Mione to Newark and made his head into a wind instrument. At this point, the Vitale gang, run by Giuseppe Vitale (real name Quincy Baedeker), made their move to take over all bootlegging in Harlem from Irish Larry Doyle-a racketeer so suspicious that he refused to let anybody in New York ever get behind him, and walked down the street constantly pirouetting and spinning around. Doyle was killed when the Squillante Construction Company decided to erect their new offices on the bridge of his nose. Doyle’s lieutenant, Little Petey (Big Petey) Ross, now took command; he resisted the Vitale takeover and lured Vitale to an empty midtown garage on the pretext that a costume party was being held there. Unsuspecting, Vitale walked into the garage dressed as a giant mouse, and was instantly riddled with machine-gun bullets. Out of loyalty to their slain chief, Vitale’s men immediately defected to Ross. So did Vitale’s fiancee, Bea Moretti, a showgirl and star of the hit Broadway musical

Say Kaddish,

who wound up marrying Ross, although she later sued him for divorce, charging that he once spread an unpleasant ointment on her.