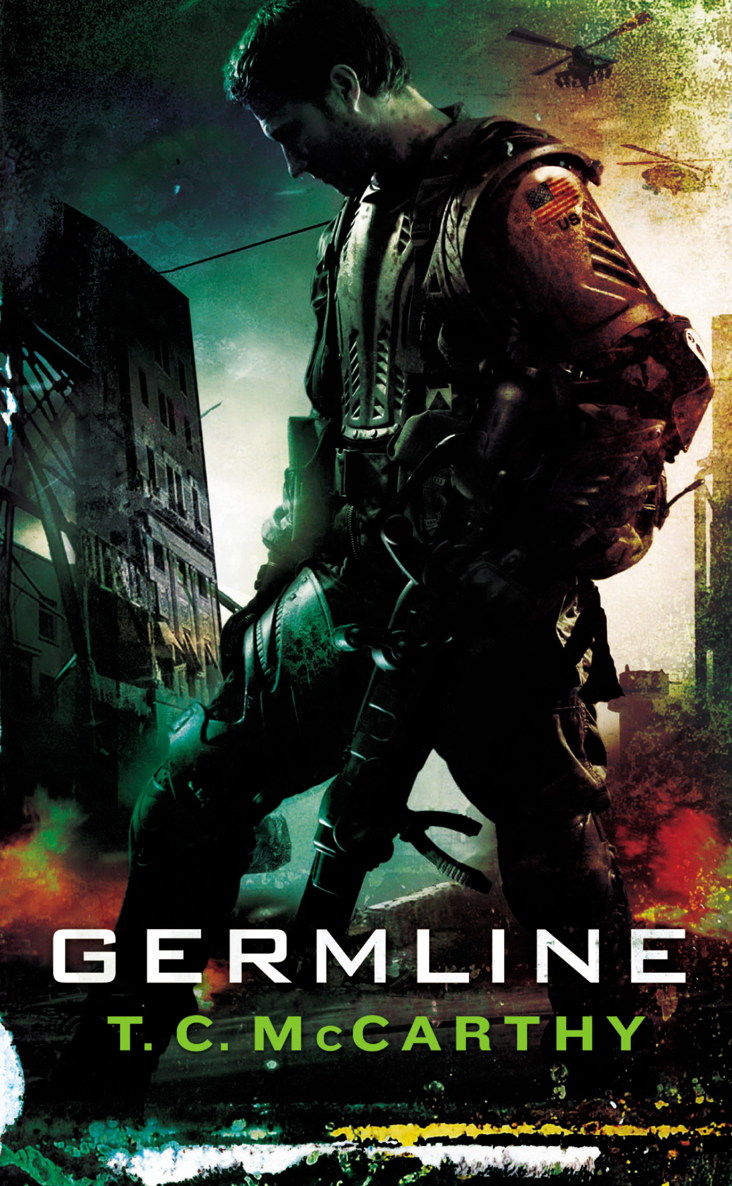

Germline: The Subterrene War: Book 1

I

’ll never forget the smell: human waste, the dead, and rubbing alcohol—the smell of a Pulitzer.

The sergeant looked jumpy as he glanced at my ticket. “

Stars and Stripes

?” I couldn’t place the accent. New York, maybe. “You’ll be the first.”

“First what?”

He laughed as if I had made a joke. “The first civilian reporter wiped on the front line. Nobody from the press has ever been allowed up here, not even you guys. We got plenty of armor, rube. Draw some on your way out and button up.” He gestured to a pile of used suits, next to which lay a mountain of undersuits, and on my way over, the sergeant shouted to a corporal who had been relaxing against the wall. “Wake up, Chappy. We got a

reporter

needin’ some.”

Tired. Empty. I’d seen it before in Shymkent, in frontline troops rotating back for a week or two, barely able to walk, with dark circles under their eyes so they looked like nervous raccoons. Chappy had that look too.

He opened one eye. “Reporter?”

“Yep.

Stripes.

”

“Where’s your camera?”

I shrugged. “Not allowed one. Security. It’s gonna be an audio-only piece.”

Chappy frowned, as if I couldn’t be a

real

reporter, since I didn’t have a holo unit, thought for a moment, and then stood. “If you’re going to be the first reporter on the line, I guess we oughta give you something special. What size?”

I knew my size and told him. I’d been through Rube-Hack back in the States; all of us had. The Pentagon called it Basic Battlefield Training, but every grunt I’d met had just laughed at me, and not behind my back. Rube. Babe. Another civilian too stupid to realize that anything was better than Kaz because Kazakhstan was another world, purgatory for those who least deserved it, a vacation for the suicidal, and a novelty for those whose brain chemistry was messed up enough to make them think it would be a cool place to visit. To see firsthand. Only graduates of Rube-Hack thought that last way, actually

wanted

Kaz.

Only reporters.

“

Real

special,” he said. Chappy lifted a suit from the pile and dropped it at my feet, then handed me a helmet. Across the back someone had scrawled

forget me not or I’ll blow your punk-ass away.

“That guy doesn’t need it anymore, got killed before he could suit up, so it’s in decent shape.”

I tried not to think about it and grabbed an undersuit. “Where’s the APC hangar?”

He didn’t answer. The man had already slumped against the wall again and didn’t bother to open his eyes this time, not even the one.

It took me a few minutes to remember. Sardines. Lips

and guts stuffed into a sausage casing. Getting into a suit was hard, like over-packing a suitcase and then trying to close it from the inside. First came the undersuit, a network of hoses and cables. There was one tube that ended in a stretchy latex hood, to be snapped over the end of your you-know-what, and one that ended in a hollow plug (they issued antibacterial lube for

that

), and the plug had a funny belt to keep it from coming out. The alternative was sloshing around in a suit filled with your own waste, and we had been told that on the line you lived in a suit for weeks at a time.

I laughed when it occurred to me that somewhere, you could almost bet on it, there was a certain class of people who didn’t mind the plug at all.

Underground meant the jitters. A klick of rock hung overhead so that even though I couldn’t see it, I felt its weight crushing down, making the hair on my neck stand straight. These guys

partied

subterrene, prayed for it. You’d recognize it in Shymkent, when you met up with other reporters at the hotel bar and saw Marines—fresh off the line—looking for booze and chicks. Grunts would come in and the waiter would move to seat them on the ground floor and they’d look at him like he was trying to get them killed. They didn’t have armor on—it wasn’t allowed in Shymkent—so the guys had no defense against heat sensors or motion tracking, and instinct kicked in, reminding them that nothing lived long aboveground. Suddenly they had eyes in the backs of their heads. Line Marines, who until that moment had thought R & R meant safety, began shaking and one or two of them would back against the

wall to make sure they couldn’t get it from that direction.

How about downstairs? Got anything underground? A basement?

The waiter would realize his mistake then and usher them into the back room to a spiral staircase, into the deep.

The Marines would smile and breathe easy as they pushed to be the first one underground. Not me, though. The underworld was where you buried corpses, and where tunnel collapses guaranteed you’d be dead, sometimes slowly, so I didn’t think I could hack it, claustrophobia and all, but didn’t have much choice. I wanted the line. Begged for a last chance to prove I could write despite my habit. I even threw a party at the hotel when I found out that I was the only reporter selected for the front, but there was one problem: at the line, everything was down—down and über-tight.

The APC bounced over something on the tunnel floor, and the vehicle’s other passenger, a corpsman, grinned. “No shit?” he asked. “A reporter for real?”

I nodded.

“Hell yeah. Check it.” I couldn’t remember his name but for some reason the corpsman decided to unlock his suit and slip his arm out—what remained of it. Much of the flesh had been replaced by scar tissue so that it looked as though he had been partially eaten by a shark. “Fléchettes. You should do a story on

that.

Got a holo unit?”

“Nah. Not allowed.” He gave me the same look as Chappy—

what kind of a reporter are you?

—and it annoyed me because I hadn’t been lit lately and was starting to feel a kind of withdrawal,

rough.

I pointed to his arm. “Fléchettes did

that

? I thought they were like needles, porcupine stickers.”

“Nah. Pops doesn’t use regular fléchettes. Coats ’em with dog shit sometimes, and it’s nasty. Hell, a guy can take a couple of fléchette hits and walk away. But not when they’ve got ’em coated in Baba-Yaga’s magic grease. Pops almost cost me the whole thing.”

“Pops?”

“Popov. Victor Popovich. The Russians.”

He looked about nineteen, but he spoke like he was eighty. You couldn’t get used to that, seeing kids half your age, speaking to them, and realizing that in one year, God and war had somehow crammed in decades. Always giving advice as if they knew. They

did

know. Anyone who survived at the line learned more about death than I had ever wanted to know, and as I sat there, the corpsman got that look on his face.

Let me give you some advice…

“Don’t get shot, rube,” he said, “and if you do, there’s only one option.”

The whine of the APC’s turbines swelled as it angled downward, and I had to shout. “Yeah? What?”

“Treat

yourself.

” He pointed his fingers like a pistol and placed them against his temple. The corpsman grinned, as if it was the funniest thing he had ever heard.

Marines in green armor rested against the curved walls of the tunnel and everything seemed slippery. Slick. Their ceramic armor was slick, and the tunnel walls had been melted by a fusion borer so that they shone like the inside of an empty soda can, slick, slick, and double slick. My helmet hung from a strap against my hip and banged with every step, so I felt as though it were a cowbell, calling everyone’s attention.

First thing I noticed on the line? Everyone had a beard except me. The Marines stared as though I were a movie star, something out of place, and even though I wore the armor of a subterrener—one of Vulcan’s apostles—mine didn’t fit quite right, hadn’t been scuffed in the right places or buckled just

so

because they all knew the best way, the way a veteran would have suited up. I asked once, in Shymkent, “Hey, Marine, how come you guys all wear beards?” He smiled and reached for his, his smile fading when he realized it had been shaved. The guy even looked around for it, like it fell off or something. “ ’Cause it keeps the chafing down,” he said. “Ever try sleeping and eating with a bucket strapped around your face twenty-four seven?” I hadn’t. Early in the war, the Third required their Marines to shave their heads and faces before going on leave—to keep lice from getting it on behind the lines—but here in the underworld the Marines’ hair was theirs, a cushion between them and the vision hood that clung tightly but never fit quite right, leaving blisters on anyone bald.

Not having a beard made me unique.

A captain grabbed my arm. “Who the hell are you?”

“Wendell.

Stars and Stripes

, civilian DOD.”

“No shit?” The captain looked surprised at first but then smiled. “Who are you hooking up with?”

“Second Battalion, Baker.”

“That’s us.” He slapped me on the back and turned to his men. “Listen up. This here is Wendell, a reporter from the Western world. He’ll be joining us on the line, so if you’re nice, he might put you in the news vids.”

I didn’t have the heart to say it again, to tell them that I didn’t have a camera and, oh, by the way, I spent most of my time so high that I could barely piece a story together.

“Captain,” I said. “Where are we headed?”

“Straight into boredom. You came at the right time. Rumor is that Popov is too tired to push, and we’re not going to push him. We’ll be taking a siesta just west of Pavlodar, about three klicks north of here, Z minus four klicks. Plenty of rock between us and the plasma.”

I had seen a collection of civilian mining equipment in the APC hangar, looking out of place, and wondered. Fusion borers, piping, and conveyors, all of it painted orange with black stripes. Someone had tried to hide it under layers of camouflage netting, like a teenager would hide his stash, just in case Mom didn’t buy the

I-don’t-

do-

drugs, you-don’t-

need

-to-search-my-room

argument.

“What about the gear in the hangar—the mining rigs?” I asked.

A few of the closest Marines had been bantering and fell silent while the captain glared at me. “What rigs?”

“The stuff back in the hangar. Looked like civilian mining stuff.”

He turned and headed toward the front of his column. “Keep up, rube. We’re not coming back if you get lost.”