Georgian London: Into the Streets (43 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

The dramatic social changes in London’s East End followed a distinct downward trend as the pressure of population increased. To the north, the villages survived longer and maintained their rural qualities well into the nineteenth century. They are visible in the distance from Hackney Marshes, and we set our course there now. Here we will find meadows, fruit farms, stabling and grazing for many of London’s thousands of coach horses, as well as springs, spas and theatres before the geography rises and we head up to the hills to find a Romantic view of London.

12. Islington, Hampstead and Highgate

To the north, the villages of Highgate and Hampstead escaped the urban creep for far longer, retaining their country status. On the way, we pass through the small settlements of Islington and Kentish Town.

Islington, bordered by the City in the south and Stoke Newington in the east, had long been a thoroughfare for traffic from and to the north of England. In the late seventeenth century, mineral waters had been discovered at what became known as Sadler’s Wells, after the owner, Richard Sadler. He claimed the warm waters were most effective against ‘

distempers to which females

are liable – ulcers, fits of the mother, virgin’s fever and hypochondriacal distemper’. Sadler’s Wells became infamous by the beginning of the eighteenth century as a notorious pleasure garden, probably not helped by the large passing trade brought to Islington by its many thoroughfares to and from the City.

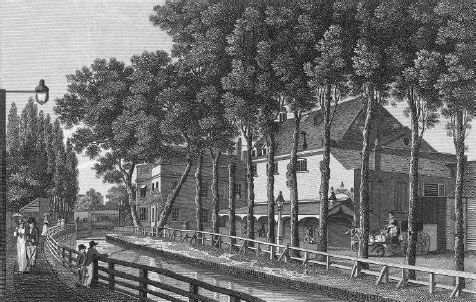

The Aquatic Theatre, Sadler’s Wells, 1813, by an unknown artist

Roads were the village’s main feature. In 1717, it had one of the earlier Turnpike Trusts, set up to maintain them. By 1735, the main roads all had houses along them, although infilling would not come until the nineteenth century. The Angel, Islington, was an inn near one of the tollhouses on the Great North Road. The courtyard of the Angel is thought to be depicted in Hogarth’s ‘Stagecoach’, and here Thomas Paine wrote passages of his

Rights of Man

during one of his stays in London in 1790–91. The sheer amount of traffic passing through the village dictated its character, and it was always a busy place populated by those who made their living from travellers, or those who wanted to be just one mile from the City of London and didn’t mind the clamour from the cattle and carriages.

Many of the buildings around Upper Street were medieval in origin, and there had been several fine manor houses in Barnsbury. The majority of the new buildings, though, were solid eighteenth-century stock, for the retired or those connected with commerce. By the 1790s, the village had two hairdressers, warehouses selling pottery, tea and fabric, as well as a wine merchant’s and a toy shop. Yet it had an air of neglect, and the green with its associated pond became drab and dirty.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Islington’s population had risen to over 10,000, and there were thriving, if slightly seedy, music halls and entertainment venues. Sadler’s Wells was now a theatre. In the first decade of the new century, it styled itself an ‘aquatic theatre’, specializing in ‘aquadrama’, where the theatre was flooded for the purpose of re-enacting naval or mythological battles or scenes. The illusion of flooding was created by a tank ninety feet long, some twenty feet wide and three feet deep. The New River, which carried water into London, was used to fill the tank. Charles Dibdin the Younger, of the Dibdin theatre family, staged the Siege of Gibraltar there, in April 1802. Children were cast as the Spanish sailors and threw themselves about in the water, ‘

swimming and affecting

to struggle with the waves’.

Islington’s true building boom came in the Victorian period. Camden and Kentish Towns were consolidated in the Victorian years, but the process began in 1791, when Lord Camden sold building rights

for 1,400 houses on his land. Horace Walpole said it heralded the spread of London to ‘

every village

ten miles around’. Kentish Town had previously been used to pasture coach horses and animals on their way to Smithfield. It had rich grazing meadows with dugout ponds in the centre, collecting rainwater in the clay soil. There were also enclosures with high grass-studded mud walls.

The walls were made

from the insides of the horns of the thousands of cows slaughtered every week at Smithfield. The exteriors went to make cheap drinking cups, or horn handles, books and tablets, but the tapered interiors formed the ‘bricks’ for these walls, which were then mortared with mud into which grass seed was pushed. Cheap, sturdy and opaque, they were the safest place to keep expensive livestock and horseflesh close to London.

From the middle of the eighteenth century until well into the nineteenth, Kentish Town had a fashionable assembly room where tea and coffee were served ‘

morning and evening’ and public and private dinners could be arranged, ‘on the shortest notice’. They also served a ‘good ordinary on Sundays at two o’clock

’, with ‘ordinary’ meaning a good roast lunch.

Islington and Kentish Town were both country villages for the majority of the Georgian period. In the minds of Londoners, as long as they could see Hampstead and Highgate from the city’s northern limits, London was still contained. Both villages had long been the resort of fashionable London: Hampstead in the summer months, to enjoy the clean air and water, and Highgate for the smart professional set, to provide commutable housing. Hampstead was built up first with the ‘

charming old red-brick

mansions which make Hampstead what it is’.

Defoe gave a heady image of the village, in 1727, when he noted in his tour of Great Britain that

Hampstead had a long association with quality schooling and intellectualism. This may have been a result of the cosmopolitan population: as far back as the sixteenth century, the names of landowners indicate Jewish and European origins. Wildwood, a house first mentioned in Domesday, was one of the most significant within the parish boundary and is remembered today in Wildwood Road and Grove. There, William Pitt the Elder recovered from his nervous breakdown, in 1767, ‘

a miserable invalid

… he refused to see anyone, even his own attendant, and his food was passed to him through a panel of the door’.

At the top of Hampstead Heath stood the vast house of Kenwood, known commonly during the Georgian period in speech and letters as Caenwood. Dating originally from the early seventeenth century, it was bought by Lord Mansfield, in 1754. He had it remodelled extensively, by Robert Adam, in the 1760s and 1770s. It was here that the Mansfields lived with Dido Elizabeth Belle, their illegitimate mixed-race grand-niece. Dido died in 1804, aged a little over forty. In 1975, Dido’s last relative, Harold Davinier, died a free white South African in a land still struggling under apartheid.

Near the Hampstead reservoir, through which the Hampstead Water Company had been supplying the West End with water since 1692, there was the Upper Flask Tavern. Clarissa fled here from Lovelace in Samuel Richardson’s novel after his ‘wicked attempt’ upon her, and the Whigs’ Kit-Cat Club used to meet here during the summer, sitting under the shade of a splitting mulberry tree which was later preserved with iron bands in memory of the club. There, too, lived George Steevens, who was famous for his edition of twenty-one Shakespeare plays published in 1766, a year after Samuel Johnson’s edition. Steevens walked into London before seven o’clock each morning to discuss Shakespeare with various eminent researchers, before making the rounds of all the bookshops, then walking back to Hampstead for the evening. Johnson was so impressed with Steevens’ work that he suggested they produce a complete works of Shakespeare together, which appeared in 1773, in ten volumes. In order to

get the work done, and with Johnson not fulfilling his part of the bargain, Steevens had, for twenty months, left Hampstead with the watch patrol at one in the morning, walked into London to his printer ‘

without any consideration

of the weather or the season’, taking with him as much work as he had ready. He would then collect the previous day’s pages, go home and edit them, before writing the next batch. He would sleep briefly before setting off for London again.

On the west side of the Heath, in Well Walk, sprang the well producing Hampstead’s renowned purgative chalybeate waters, drawing hundreds of Londoners on sunny days. The waters contain ‘

oxyde of iron

, muriates of soda and magnesia, sulphate of lime, and a small portion of silex; and its mean temperature at the wells is from 46° to 47° of Fahrenheit’. In the reign of Charles II, a halfpenny token stamped with the words ‘Dorothy Rippin at the well in Hampsted’ on the back was issued, exchangeable for a pint of water. In 1698, Susanna Noel with her son Baptist, 3rd Earl of Gainsborough, gave the well along with six acres of ground to the poor of Hampstead. From here, the water was carried every day for sale to Holborn Bars, Charing Cross, and throughout the streets, for purchase by those who preferred Hampstead water.

A Pump Room was built on the south side of Well Walk, which was opened in August 1701 with a concert. On the northern side of Well Walk was built the Long Room for dances and assemblies. These parties were a fixture of Hampstead and London life. The addition of the Pump Room transformed Hampstead into a ‘

spa town

’ in its own right, and by the 1760s, it had 500 dwellings. The artist John Constable lived for a while in Well Walk, at Number 6, though he continued to go into work to his London studio.

By the time he was living in Hampstead

, many people commuted daily to the city, and by 1834, eight omnibuses were making twenty journeys each day. London merchants had favoured Hampstead as a retreat since the Civil War, but now it became possible to live there and still work in their counting houses. The atmosphere was wealthy, liberated and educated.

Like Hampstead, Highgate had become a wealthy village in the late sixteenth century. Highgate village straddles the border between Hampstead and Hornsey. It became built up in the seventeenth and

eighteenth centuries, with good houses and a prosperous high street. Like Hampstead, and Hackney, it had originally been a place to enjoy fresh air and peace, whilst staying close to London. Highgate’s church, St Michael’s, is at the same height as the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral: 365 feet. The soil and altitude made the area ideal for the growing of soft fruit, and from Islington to Highgate there were many fruit farms. There were also dairy farms, and the absence of smallpox in the milkmaids led Londoners to credit Highgate with having particularly healthy air, which kept the girls’ skin fresh and clear. It was from this high point that Boswell ‘went in’ to the theatre of London on 19 November 1762, after the long journey from Scotland, recording in his journal: ‘When we came upon Highgate Hill and had a view of London, I was all life and joy.’

Highgate could not rival Hampstead socially, but it acquired one coup with the arrival of Harriet (née Mellon), the widow of the banker Thomas Coutts, who took a lease on Holly Lodge, on the west side of Highgate Hill, after her first husband died. Her rise from actress to desirable mistress was not unlike that of Coutts’s own ancestor and fellow Highgate resident, Nell Gwynne. Like Nelly, of ‘the ten or twelve ladies who have been raised from the stage to wear coronets, few names stand forth more pleasantly than that of Harriet Mellon’. Her biographer noted, ‘

It is not known

who was her father, though probably she had one,’ and that she was born on 11 November 1777, behind Lambeth Palace. Her father was later said to be a chimney sweep from Sheffield, or perhaps a soldier in the Madras Infantry.

Harriet made her debut at the Drury Lane Theatre, in 1795, but it wasn’t until 1805 that she met the seventy-year-old Thomas Coutts. She was his mistress until the death of his wife, in 1815, and they married soon after. They had to marry twice, after the first ceremony was mysteriously deemed invalid. Upon her marriage she became one of Britain’s richest women, and she was desperate to become London’s most popular hostess. Her desperation to be liked by the

haut ton

was often caricatured, but her kind-hearted, flamboyant style and her love for entertaining gradually won them over. Thomas died in 1822, leaving Harriet his fortune and his share in Coutts Bank, much to the annoyance of his daughters from his first marriage. Harriet, however,

refused to be cowed and gave them all generous allowances. In 1827, she also brought their wrath and London’s scorn upon herself again when, aged forty-nine, she married William Beauclerk, the 26-year-old Duke of St Albans. The caricatures were even more scathing, but just as her first marriage had been a happy one, it seemed that the new Duchess of St Albans’ cheerfulness and her husband’s easygoing nature meant they were content enough together.

Yet William’s family were very rude to his new wife. Harriet had her fill of unpleasant in-laws, and when she died, in 1837, a clause in her will specified that were any of William’s family to come and stay with him for more than a week at any of the properties she left him, all her bequests to him would cease. The Duchess of St Albans left most of her wealth, the vast sum of £1.8 million, to Thomas Coutts’ granddaughter, Angela. Angela Burdett-Coutts would become Victorian London’s greatest philanthropist until she forfeited the fortune, aged sixty-nine, by also marrying a 26-year-old. It wasn’t the cradle-snatching her step-grandmother’s will objected to, but that he was American: a clause specified that Angela must not marry an ‘alien’. The American husband lived on at Holly Lodge after Angela’s death. When he died, in 1922, the estate was developed as bedsit accommodation for young women who came to London to work after the First World War left the City in dire need of clerks and secretaries. For a long time, the housing remained for women only.