Georgian London: Into the Streets (31 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

When Margaret’s son died, in 1810, the vase was placed on loan with the British Museum. On 7 February 1845, a youth of Irish origin entered the Museum and smashed the vase to pieces, blaming his actions on a week of intemperance. He was fined £3. Meanwhile, the vase lay in 139 pieces. The museum staff managed to put it back together and return it to the display. The 4th Duke of Portland declined to prosecute the man, on the grounds that he had mental health problems. Despite its battered history – buried, smashed, reassembled – the Portland Vase is still on show in the British Museum, a truly remarkable object and part of Margaret Cavendish’s little-known legacy to London.

If the Harleys gifted London rare books and objects, another Marylebone collector was equally influential in contemporary music. James Brydges, Duke of Chandos, who was one of the earliest to buy a plot in Cavendish Square, was also was one of Georgian London’s most important music patrons.

Brydges’ finances took a tumble in the South Sea Bubble. He originally acquired the whole of the north side of the Cavendish Square project, but scaled himself back to building two large mansions on the north-east and north-west corners. He lived in the north-western one, although he would never complete it, and eventually sold both mansions to buy Ormonde House, in St James’s Square. This impetuosity and lack of commitment characterized Brydges’ business dealings. In the fields just north lay the Marylebone Basin Reservoir, supplying water for the square and other parts of the village. He planned to make a fortune from a water company for the new development, but that too would fail; during 1769, the Basin was filled in to build Mansfield Street. Marylebone parish had many lakes and ponds which proved fatal on more than one occasion.

The St James’s Chronicle

for 8 August 1769 relates a tragedy in the small and dangerous pond nearby, known as The Cockney Ladle. There, ‘two young chairmen were drowned. They had been beating a carpet in the Square and being warm and dirty had decided to have a bathe, not being aware of how deep the pond was.’

Brydges, though a poor businessman, was a fine patron of art and music. He was a lover of Italian opera and a member of the Society of Gentleman Performers of Music. He was determined that his household should be dedicated to furthering his love of music. With Burlington, he was involved in the early Royal Academy of Music, and an orchestra played to Brydges even as he ate. Like Burlington, Brydges collected antiques and European objects.

He was generous with his houses and his collections. Servants were allowed to earn extra money by admitting guests to the house and taking them around for tours. Anyone was admitted, provided they were smartly dressed. They were led on a tour of the collection and given a cup of tea or some other refreshment. If they were of sufficient interest, the Duke was alerted and came down to meet them.

Brydges was remembered as a good-humoured man. In the only duel he ever fought, he disarmed his opponent, apologized and invited the man for dinner that evening. His own words on his collecting habit are summed up by ‘

we knick-knack men

when once a fine thing is bought for us like other children are wonderfully impatient till we have it’.

Cavendish Square still retains a cheerful country air. In the 1770s, Billy Ponsonby, Earl of Bessborough, leaned on the railings here and watched the world go by. He lived at 3 Cavendish Square with his wife, Caroline. They had two daughters and a son together, but Caroline died when the children were in their teens. Her devoted widower took to wearing her diamond buckles on his shoes on his lonely perambulations around the growing village north of Oxford Street. A familiar sight on the streets, he

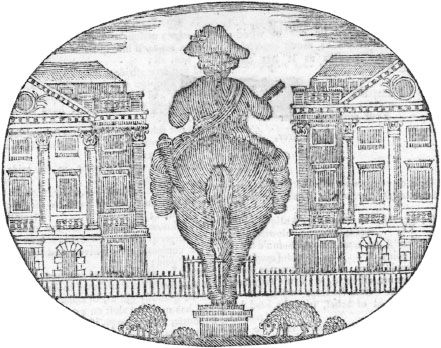

Looking north from Cavendish Square, with the rear view of the statue of the Duke of Cumberland, 1771. The sheep were removed later that year

In the late 1780s, Billy’s charwoman at Number 3 was ‘took sudden’ and had her baby in the house. He was named Billy.

Billy grew up in the house

until Billy Ponsonby’s death, in 1793, ‘for whilst he lived [his mother] wouldn’t leave him, not for nothing’.

Aged nineteen, Billy took to selling watercress about the streets but he had to stop as the market wouldn’t support him, his mother and his aged father. He struck upon the idea of working as a crossing-sweeper in Cavendish Square: ‘I’m known there; it’s where I was born and there I set to work.’

Crossing-sweeping was one of the humblest professions, but Billy was known as the ‘aristocratic’ crossing-sweeper. In wet weather he could be seen sheltering ‘under the Duke of Portland’s stone

gateway’. Billy’s unique position as street furniture gives an insight into the charitable inclinations of the Marylebone rich. Some gave him clothes, some money, one ‘a shilling and a religious tract’. Billy remembered his religious benefactor as ‘a particular nice man’.

Billy was such a familiar sight around the square that he was given odd jobs, such as scouring the mild-steel knives, taking cash to the bank for the Duke of Portland, and even cashing cheques for other gentlemen. He attended houses early in the mornings to clean shoes, knives or put letters in the post: ‘It’s only for the servants I does it, not for the quality.’ In a twist of social hierarchy, although he was entrusted with £80 in cash by one gentleman, the servants didn’t allow Billy to intrude into the domestic setting beyond the kitchen, where he received ‘broken foods’. Like anyone in a job for a long time, Billy remembered ‘the good old days’. In particular, he wasn’t fond of the new invention of tarmacadam – or ‘muckydam’, as he liked to call it – reducing the life of a broom from three months (on cobbles) to a fortnight.

The story of the two Billys of Cavendish Square highlights the area’s slightly more relaxed social structure. After all, many of the local residents, no matter how wealthy, were outsiders. Marylebone was popular with officers of the East India Company, who often returned to England with their racially mixed households. However, these mixed households were not only East Indian; many white West Indian families had returned to London to spend their sugar money.

On 31 January 1765,

The Public Advertiser

declared: ‘Portman Square now building between Portman Chapel and Marylebone will be much larger than Grosvenor Square; and that handsome walks, planted with Elm Trees, will be made to it, with a grand reservoir, in the middle.’ Construction on the north side did not start until 1773, when Robert Adam undertook to build a house for Elizabeth, the Countess of Home. At the same time, Elizabeth Montagu, whose star was firmly fixed in London’s social firmament, left Hill Street in Mayfair and took the lease of the large plot which ran, unusually,

across the south-west corner. She employed James ‘Athenian’ Stuart to raise a huge mansion in competition with her neighbour. The Countess of Home was proud of her colonial heritage. Elizabeth Montagu and her bluestockings were violently opposed to slavery. As the question of slavery became increasingly uncomfortable, the battle lines were drawn in Portman Square.

The Countess of Home had been born Elizabeth Gibbons, in Jamaica. She married young, to the son of the Governor; his death, in London in 1734, had left her a very wealthy eighteen-year-old. Social mobility was high in the West Indies, and the rougher, hardier European men and women often flourished. A commonly held view was that the islands were ‘

the Dunghill

wharone England does cast forth its rubbish’. Jamaica started out as a trading island but when it gave itself over to sugar plantations there were opportunities to make huge fortunes. European mortality rates were staggering at around 27 per cent a year, owing to ‘bad fruit’, hurricanes and yellow fever. With the rate of attrition so high, marriages did not last long and relatively few islanders succeeded in bringing up families. Native-born white islanders surviving to adulthood were scarce. The successful few were opportunists and adventurers. Added to this potent mixture, as well as the ever-present spectre of violent uprising and death, was the massive wealth attainable through sugar.

The average white

plantation owner on Jamaica was ten times richer than those in mainland America.

Sugar was an increasing presence in London. In 1700, national consumption was 4lbs per head per annum; by 1800, this had grown to 18lbs. Jamaica and its cash crop was the jewel of the British Caribbean. White Jamaicans were starting to exert an influence on British politics and the City. The planters and merchants who represented them formed an influential lobbying group which successfully opposed the attempt to introduce large quantities of East Indian sugar to Britain.

Elizabeth arrived in London as a rich planter’s wife. But after her husband’s early death, she disappears and doesn’t reappear until 1742, when she married the Earl of Home. She was thirty-eight, he was some years younger. He deserted her in the first year of their marriage. Upon his death, in 1761, his possessions were auctioned and

Elizabeth bought back the silver dinner service he had taken with him. William Beckford, himself an heir to sugar money, described Elizabeth as a ‘

flamboyant eccentric

, given to swearing like a trooper’. In 1772, aged seventy, she decided to build a new house on the north side of the square, where she was ‘

known among all

the Irish Chairmen and riff-raff of the metropolis by the name and style of the Queen of Hell’. Money was no object when Elizabeth engaged James Wyatt to design her new house, in June 1772. Wyatt was only twenty-six, and unable to keep up with the amount of commissions he was receiving. The two fell out. Elizabeth sacked him and brought in Wyatt’s great rival, Robert Adam, to finish the job.

Adam’s taste coupled with Elizabeth’s money produced one of London’s finest interiors. Adam blended formal with informal, blurring the line invisibly between family and servants whilst keeping the two entirely separate. In Home House he was triumphant, and the house was used as an entertaining space of the highest order.

Elizabeth’s heyday in Home House coincided with the consolidation of virulent abolitionist feeling amongst London intellectuals. Public sentiment was turning against the ‘sugar rich’, their unbelievable wealth and the methods on which it was founded. William Cowper wrote a pamphlet addressed ‘To Everyone Who Uses Sugar’, reproving those who used it with: ‘Think how many backs have smarted, for the sweets your cane affords.’ It was no hole-in-the-corner publication, and was exactly the sort of thing the West Indian planters were hoping to avoid. East Indian tea accompanied by West Indian sugar had become an English staple, but now the ordinary man and woman were exhorted to think, to consider the reality behind this daily treat, and: ‘As he sweetens his tea, let him consider the bitterness at the bottom of the cup.’

On the other side of the square were the tea parties of Elizabeth Montagu and her intellectual circle.

Montagu House was vast: the housewarming party was a breakfast for a modest 700 guests. Elizabeth later held a May Day breakfast for London chimney sweeps, where they had only to present themselves on the front lawn to receive a celebratory meal of beef and a pudding. Her literary salons continued, as they had in Hill Street,

but the topics of the conversation were evolving with the times, and abolition became a constant feature.

The bluestockings put great store by intellectual equality between the sexes and by ‘conversation’. Their debates reflected popular feeling at the time. On 20 March 1783,

The Gazetteer

ran an advertisement asking, ‘

Are there any grounds

for supposing that the understandings of the female sex are in any respect inferior to those of the men?’ There were even debates asking ‘

Ought not the Word Obey

to be struck out of the Marriage Ceremony?’ Elizabeth’s salons were held in the beautiful drawing rooms of Montagu House, where chairs were ranged around her in a semicircle and she literally acted in the role of ‘chairwoman’. Samuel Johnson said of her: ‘

She diffuses

more knowledge than any woman I know, or indeed, almost any man.’ Hester Thrale described her, kindly, as ‘

brilliant in diamonds

, solid in judgement’. Her friends included Elizabeth Vesey, Sir Joshua Reynolds, David Garrick, Samuel Johnson, Fanny Burney, Hester Thrale, Margaret Bentinck and the abolitionist William Wilberforce.