Georgian London: Into the Streets (22 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

…

soon fell in with a fleet

of gardeners … I landed with ten sail of apricot boats at Strand-bridge, after having put in at Nine Elms, and taken in melons. We arrived at Strand-bridge at six of the clock, and were unloading, when the hackney-coachmen of the foregoing night took their leave of each other … I could not believe any place more entertaining than Covent Garden, where I strolled from one fruit-shop to another, with crowds of agreeable young women around me who were purchasing fruit for their respective families.

Women dominated the market, and Steele tells of their cheerful, sometimes bawdy exchanges with porters and boatmen. Many labour under the misapprehension that Londoners of the past ate either nothing but meat, with no fresh vegetables or fruit, or they ate no meat at all and lived upon bread and cheese. The fruit mentioned in Steele’s article are apricots and melons, which were grown in specialist ‘pits’ in Vauxhall. Pineapples and purple sprouting broccoli were also grown there. Salads and tomatoes seem to have been universal. In the cooler

seasons Londoners resorted to cooked vegetables, and Frenchman Henri Misson de Valberg remembered his roast beef ‘

besiege[d] with five or six Heaps

of Cabbage, Carrots, Turnips, or some other Herbs or Roots, well pepper’d and salted and swimming in Butter’.

The market fostered a healthy tavern and alehouse trade, with every level of toper catered for. Ned Ward required only an alehouse selling quality pints that would ‘

not fill my guts

with thunder’, but François de La Rochefoucauld praised the local taverns as ‘

fine inns

where it is accepted that men go for prolonged bouts of wine drinking’. Nearby was Teresia Constantia Phillips’ sex shop, the Green Canister, which she opened around 1732 after breaking up with her long-term keeper. During her time as a courtesan, Con had learned a thing or two, and so she set up shop in Half Moon Street, which is now Bedford Street. Printed handbills advertising her wares were given out in the street by link boys earning a few extra pence.

Con’s ‘preservatives’, or condoms, were so famous they featured in Plate Three of Hogarth’s ‘Harlot’s Progress’. They were made from the caecum of a sheep’s intestine, and the standard length was between seven and eight inches, secured with a coloured ribbon about the base. The treatment process to make them thin and flexible was extensive, and they were tested by blowing them up to check for leaks. They were soaked in water then squeezed out before use, to keep them elastic and comfortable. They certainly had some degree of efficacy, and they were popular. Casanova swore by them, and bought them by the box whenever he found a reliable source.

Sex shopping of all kinds aside, the Strand was the main food shopping centre for the West End. Covent Garden Market provided fresh produce, almost all of which could be delivered by messenger boys or porters. Home delivery provided employment for thousands across the city. Coal was delivered to the house by men who rented storage space in cellars and then carried individual sacks or small barrowloads to each house. This was the same with water, which was usually clean water from a local well but also came from as far away as Epsom or even Buxton, for the discerning palate. Milkmaids carried their milk about the streets using a yoke and

shouting their wares. Their hours were long, and their pay low. Independent self-employed milkmaids were often Welsh. Those who offered a premium service led their cow on their rounds and milked it at the door. Babies and those with a cow’s milk intolerance could have milk from the asses who were also led around the streets. Pretty girls were deployed from the market gardens of Fulham and Chelsea to sell perishable foods and herbs – such as cherries, asparagus and lavender – from baskets carried on their heads.

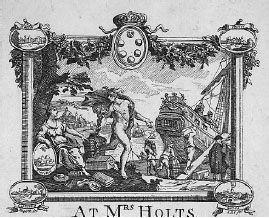

Although most food was sold by roving basket carriers, or from market stalls, some foods with a longer shelf life, such as cheeses and preserved meats, were sold in large warehouses around the Strand. Many of these warehouses specialized according to nationality, including Mrs Holt’s Italian warehouse, the trade card for which was designed by William Hogarth.

Italian diplomat Lorenzo Magalotti remarked in his diary that

these shops were ‘

mostly under the care of

well-dressed women’ who were aided by their young apprentices. This seems to have been an excellent system, appealing to almost all buyers.

Italian Warehouse at ye two Olive Posts in ye Broad part of the Strand almost opposite to Exeter Change are Sold all Sorts of Italian Silks as Lustrings, Sattins, Padesois, Velvets, Damasks Fans, Legorne Hats, Flowers, Lute & Violin Strings Books of Essences, Venice Treacle, Balfornes, &c. And in a Back Warehouse all Sorts of Italian Wines, Florence Cordials, Oyl, Olives, Anchovies Capers, Vermicelli, Bolognia Sausidges, Parmesan Cheeses, Naple Soap

Later in the century, fixed shop windows became popular, with a permanent and often elaborate display of books, wallpapers, paintings, carving, silks and fabrics, gloves and lace. Many tailors’ and dressmakers’ shops doubled as places to meet and drink tea and coffee. Most sold clothes off the peg, which could then be altered by seamstresses who hung out large wooden needles from their windows when they were available to work. Pet shops on the north side of Covent Garden sold everything from song thrushes caught on Hampstead Heath to marmoset monkeys in little outfits. There were opticians who tested the eyes and sold spectacles, both made to measure and off the peg, with the ‘focus’ engraved on the arm. Plain green and blue lenses were also used as sunglasses. This was an idea imported from Venice, where reflections from the lagoon caused light sensitivity.

Shops were dependent upon the rhythm of daylight hours. Food shops opened at dawn and stayed open until they had sold out for the day, or until dark. Most other shops opened at 8 a.m. and stayed open until nightfall, or 9 p.m. in the summer. There were few chain stores, and each shop traded as they saw fit – much more interesting than the modern high street. I particularly like the sound of Arabella Morris’s garden centre, also on the Strand.

All along the Strand were small outlets selling clothes and accessories, as well as books. The Exeter Exchange was built at the end of the seventeenth century, opposite the old Savoy Palace and close to what became Exeter Street. It was largely occupied by women selling hats, dresses and lace. This was all to change in 1773, when the upper rooms were let to the Pidcock family. The Pidcocks were entrepreneurs, specializing in exotic animals. Soon they had established a menagerie on the first floor of the Exchange. Like the Tower menagerie, the big cats were popular, but the biggest attraction was the elephant.

Elephants were alien creatures to most people in Britain, and to imagine the sound of cats roaring and an elephant trumpeting over the noise of the horses and people on the Strand is rather exotic. But caged on an upper floor, observers soon noted that the animals were not happy and developed a ‘peculiar movement’ whilst in captivity.

In 1810, the

Lady Astell

arrived in the East India Docks, in Blackwall. She belonged to the East India Company, and on board was a young male elephant. He was called Chuneelah, or Chuny for short. Chuny completed a short but successful stint in the Covent Garden Theatre. There, he would arrive on stage and then deviate from the planned scene by interfering with his fellow actors’ clothing, or departing altogether. Edward Cross, the then proprietor of the Exeter Exchange, acquired him immediately. He was a huge hit, but Chuny’s life was far from perfect. Without any exercise at all, he was growing. And growing. He was soon ‘

such a size

that it was with difficulty he could lay down in his den, which so worried him that he became more mischievous and required additional care’.

On the morning of 1 March 1826, Chuny could stand no more, and started smashing himself against the bars. His musth had arrived, and his patience was at an end. Edward Cross knew he had to do something. He ran across the road to Somerset House, to ask the soldiers stationed there to come and shoot Chuny. The soldiers came. They shot at Chuny behind the half-demolished grill of his cage. He became enraged by the bullets and had almost broken through his cage, threatening to get out on to the unreinforced portion of the floor. One of the riflemen recalled how, now that their course had been set upon, they had to stop Chuny getting out of his cage at all

costs, or ‘

through the whole flooring

we should have gone together, lions, men, tigers and birds’. The soldiers panicked until an officer ordered them to shoot all at once. After a second wave of bullets, Chuny finally died, collapsing heavily on to the strengthened floor.

On that Saturday morning,

The Times

reported how a pulley had been set up on the first floor of the Exeter Exchange. Chuny was suspended and flayed, and his skin was sent to Greenwich for tanning. On Saturday afternoon, during the dissection, a steak was butchered from his rump and cooked on the spot, with several people (including the dissecting surgeon) sampling it. As darkness fell, Chuny’s guts were carried down to the river and thrown off Westminster Bridge.

Edward Cross did not know what to do next. He had Chuny’s skeleton reassembled and placed back in the cage. Awareness of cruelty to animals was gaining ground rapidly. The papers were full of arguments both for and against captive animals, including one in

The Times

on Friday 10 March, which was signed from Chuny himself, and told the readers:

To place an elephant, or any beast, without a mate, in a box bearing no greater proportion to his bulk than a coffin does to a corpse, is inhuman; and there can be no doubt that confinement and the want of a mate caused the frenzy which rendered it necessary to destroy the late stupendous and interesting animal at Exeter Change.

Chuny’s fate gave many Londoners pause: an animal that had been so amazing to them, that had picked up their coins and handed them back, and held on to their fingers with his trunk, had been reduced to a lump of running gore in an attic room. It furthered the cause for more ‘natural’ habitats. In 1857, one of the shooters involved that day wrote to Francis Trevelyan Buckland, a leading zoologist, to set the record straight about what had really happened. The rifleman remembered how Chuny ‘

folded his forelegs under him

, adjusted his trunk, and ceased to live, the only peaceful one among us cruel wretches’. Chuny was eventually taken to the Hunterian Museum and stayed there for over a century, until he was blasted to pieces once more during the Blitz.

A MULTITUDE OF OBSCENE PRINTS

’

To the south of the Strand was a labyrinth of medieval streets. Francis Place remembered how many of the area’s children were ‘

infested with vermin’ and ‘used to be combed once a week with a small toothed comb onto the bellows or into a sheet of paper in the lap of the mother

’. It was a poor and shabby place, which suited itself well to the sale of second-hand books and prints. In particular, Wych Street and Holywell Street were both full of booksellers specializing in cheap printed works and erotica.

Continental erotica had been around in England since at least the late sixteenth century, but designed for a small, wealthy market whose pleasures were largely literary. After the Restoration, Charles’s relaxed court brought sexuality into the public sphere, and popular works of both literary and literal pornography began to appear. French pornography was deemed particularly saucy, and many titles included faux French words or phrases. Most English pornography from the same period is dominated by gross obscenity and defilement. Continental versions were more sophisticated and varied. The market for them flourished. Samuel Pepys probably represents the average consumer: he had a copperplate print of a naked Nell Gwynn above his desk at the Admiralty; and in the early part of 1688, he purchased a copy of

L’École des Filles

from John Martin, his bookseller. On a February Sunday, ‘the Lord’s Day’, as he noted in his diary, he went to the office to do some work and have a little read of his new purchase, ‘which is a mighty lewd book, but yet not amiss for a sober man once to read over to inform himself in the villainy of the world’.

In 1748, English erotic literature really got going with the publication of John Cleland’s

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure

, or

Fanny Hill

. This marked a departure into that growing literary form, the novel.

Fanny Hill

is markedly different to its predecessors. It is narrated by a young woman and tells of her arrival in London and subsequent ‘seduction’ into becoming a prostitute. As she then climbs through the ranks to become a courtesan, Fanny relates the stories of what she sees and gets up to. It contains all the usual

themes of English pornography but also features lesbianism, and first editions contained an episode in which Fanny related a male homosexual encounter in detail. This was later cut.

Fanny Hill

is remarkable in two ways: firstly for its form as a novel, and secondly because of the happy ending Fanny is given, marrying the boy she falls in love with at the beginning of the story.