Full Moon (8 page)

The Rangar, well pleased, cleared his throat. His grandson, with the sword

across his knees, hitherto as motionless as a moonlit carving, leaned forward

to listen. His eyes obeyed the gesture of the old man’s right hand pointing

toward Gaglajung.

“Your honor knows the ballad about Ranjeet of the Ford? Yonder the ford

lies—this side of Doongar Village, between us and Grayne sahib’s camp.

That castle commanded the ford in the old days. It was Ranjeet Singh’s. None

could burn him out of it, and lie was known as Ranjeet of the Ford—a

wonder of a man, who swore to.have his will of life up yonder and not die at

all but leave earth in a way more pleasing. It befell otherwise. She who died

last in that place, is—men say so—there yet. Some say they have

seen her.”

“Have

you

seen her?” Blair asked.

The old man stared, but Blair was looking at the night. Only the grandson

betrayed excitement; he leaned farther forward. The Rangar continued:

“I have seen and heard strange things in my day. God’s truth is what

matters. She of whom I speak was known by a name, that means Queen of the

Moon. It was not hers in the beginning. All astrologers are liars, saith the

Prophet. I believe in none of their abominations. Nevertheless, they say that

certain stars, when seen together near the moon, mean love and war in

wondrous combinations, and an ill end.

“Ranjeet Singh desired her. His will was law. He stole her from her

father’s hold by Abu, after three years’ fighting. It is said that as he bore

her home lie saw two stars beside the moon reflected in the ford, when he

paused to water his horse. She, his prisoner, still hating him, he gazed into

her eyes and renamed her Queen of the Moon, From that hour they two loved

each other.

“Great was her love for him. The minstrels sing of it. They say she

learned secrets that only the Brahmins know. And some say she did what

Ranjeet of the Ford did not escaped death. But such is the talk of idolaters,

and may the curses of the Prophet rest on such abomination. So much Ranjeet

loved her that he rode unwillingly when his plighted words compelled him to

take up arms again. He was summoned afar off, to the aid of a Prince who had

once befriended him. In such matters no Rajput is his own master. He obeys

his oath, no matter to whom he pledged it. Ranjeet rode forth, vowing not to

come back save with honor.

“Her honor and his were one. She swore— for in those days they were

women

—she would hold that crag of his until he should return

victorious, or unto death and forever. She and her women, and boys and old

men were the garrison when Ranjeet led all his warriors away to aid a friend

in need. More than one king slept ill at ease then, thinking how “she might

be had for the taking. By Allah, she was worth a campaign if there is truth

in a tenth of the tales of her! Queen of the Moon men called her, and they

said she knew great secrets. Three kings laid siege to that fortress yonder.

They agreed between them that the first to storm the battlements should,have

her, and her secrets also, but the other plunder should be equally

divided.

“They plucked the uncaught eagle. She and her women held that height so

stubbornly that on this countryside to-day we say of a vainglorious boaster

‘he taketh Gaglajung.’ In armor, she led all sorties. She and her women held

the breaches in the walls, while boys and old men toiled at the repairs. They

said she knew the secrets of the Moon and that the Moon-god and the gods of

day and night were all her servants. But there came a herald from the three

kings, saying Ranjeet Singh, defeated, on his way home, had been taken

prisoner. He was the prisoner of the three kings.

“In a fetter to her, he bade her yield, as. the price of his freedom. The

three kings were casting lots for her when the herald brought back her

answer, saying she believed no word of it, well knowing that Ranjeet Singh,

her lord, was a man to whom honor and life were one, whereas the writer of

that letter was without honor, like unto themselves. But Ranjeet was unworthy

of her.

“The three kings set Ranjeet Singh arrayed in armor on a horse, and showed

him to her. Then again they sent the herald. He returned again answering,

‘Nay, it is not he, because where is his honor?’

“Then, it is said, they tortured Ranjeet Singh, and he betrayed a hidden

passage. That night they assaulted—all three kings with all their

strength, from three sides and by the secret passage also. By Allah, they had

light to see by! She burned the place. She and her women died in that

furnace. But some say—may the lie blister their throats!—that she

died not at all. It was full moon.”

“What had that to do with it?”

“I know not. But they say that at full moon she walks the battlements and

waits there yet for Ranjeet Singh to come with honor. Some say they have seen

her spirit. As for me, I am a Sufi, and I think a man may inquire about life

and death. But not too idly—nay, nor listen to such tales as that.

“The three kings slew Ranjeet Singh. Despising him, they put him in a

tiger’s cage. When he was devoured they let the tiger go, declaring the brute

had done well. Thus sprang the legend that Ranjeet Singh incarnates in a

tiger. A foolish legend, but men believe it. Look, sahib—nay, yonder,

to the left a little.”

Far off, probably a mile away, or more, a little yellow light moved slowly

up and down, then vanished.

“He is coming,” said the Rangar. “Ranjeet Singh, the superstitious call

him. And they say. Slay him ever so often, ever he is reborn. They say he

must prowl in that shape until she shall descend from Gaglajung and forgive

him. Who knows? I am against all superstition. But I have heard wilder tales

than that.”

Blair got up and examined the breach of his rifle. The Rangar was old and

the boy young, so that neither had part in the hunt. Blair followed a lean,

loose-limbed shikarri, along the dry bed of a watercourse for upward of a

mile, until they reached a bend where moonlight formed an amber pool at the

foot of a huge rock. The shadow of the rock struck forward into that pool of

light. Beyond, the dry watercourse entered a dark gorge with jungle-clad

walls. To the right, beyond the rock, a smaller, stone-strewn watercourse

descended from Gaglajung in shadowy zigzags, reaching the dry pool amid

boulders beside a gnarled tree.

The shikarri whispered, “When he has killed, sahib, he goes by that way,

up the flank of Gaglajung, where he dens in a cavern. But to-night he has not

killed. He is angry.”

So was Blair angry. What the devil was Henrietta doing, wandering about

that countryside? He took his stand with his back to the rock, in soot-black

shadow, motionless. The shikarri crouched near him behind a boulder. There

were sounds not far off. Twigs snapped. A jackal yelled homeless anguish.

Silence returned, heavy and as solid as the darkness of the breathless

jungle. For twenty minutes night, time, silence and suspense all brooded

peril, forefelt, until human nature yielded to the strain and time dimmed

imagination. A heavy, sullen sounding footfall came at last like a sound in a

dream. The shikarri whispered:

“Bagh hai!”

Gray in the dimness, as sudden as if evolved out of eternity that moment,

a tiger stood ghostly and vague in the throat of the gorge—motionless.

The moonlight shone pale on his eyes. His head was flat with back-laid ears.

He heard a sound behind him, wheeled and vanished.

Two minutes passed—two eternities. then he stood there again, in the

same spot, couching his weight between his shoulders. Murderous eyes that saw

Blair Warrender could not interpret what they saw. They awaited motion; he

made none; he and his rifle were one still shadow, within a darkness. On the

flank of the gorge in the dark a twig snapped sharply. The tiger vanished

like a shadow, nowither. He was simply not there. Three minutes, by Blair

Warrender’s pulse-beat. Then, out of the stillness behind the boulder on his

right hand, the shikarri’s tongue clucked on his cheek. That sound might mean

anything, but certainly not nothing, from that shikarri. Warrender spared him

a glance, but his eyes made only half the circuit; they were arrested midway

by a shadow moving on the bed of the smaller watercourse. There was no

sound.

Suddenly the tiger muttered—coughed— roared—three sounds

from three directions. He had made a circuit of the moonlight and lay

crouching somewhere to the left, opposite the smaller watercourse. He could

not be twenty paces away. His eyes became visible, nothing else. He appeared

to be watching that new shadow that had set the shikarri’s warning tongue in

motion. There was sixty seconds’ silence. Then he crept out into moonlight,

tense, with his weight low, crouching for the rush that bears home spastic

death on fang and claw.

Blair Warrender and his rifle became one entity. Flash, crack, echo were

inseparable from the roaring snarl of anger as the tiger tell biting the

wound that stung him, rolled into the shadow of a rock, recovered and then

rushed at the throat of the smaller watercourse.

A shot followed—hit him—hit hard. He roared and turned to face

the enemy. A third shot rolled him over and he lay still, except that his

claws tore the sand, anger surviving death by fifty spasms.

The shikarri began tossing pebbles, keeping the advantage of the boulder.

There were sounds all around in the dark, but no one showed himself, not even

when Blair reloaded and stepped out into the moonlight. A retreating jackal

whimpered the tiger’s requiem, obscene and ribald.

“Three shots?” said a woman’s voice. The shadow lengthened in the throat

of the smaller watercourse. There was a sound of footsteps, rubbered, on

smooth rock. “Is it Ranjeet Singh or just an ordinary tiger?”

“Stay where you are!” Blair answered. He had seen too many dead tigers

come to life to take unnecessary risks. He hurled a big stone at the carcass,

then went close and prodded with the end of his rifle-barrel. “Yes,” he said,

“three shots. Is it Henrietta?”

She sprang to a small boulder and stood in full moonlight with her hands

behind her, wearing no hat. Wavy, blond hair that looked like spun gold hid

her face in shadow. There was an edge, like an aura, of moonlight that,

revealed her figure outlined under a smock of some flimsy material.

“Is it Ranjeet Singh?” she repeated.

Anger hardened Blair’s voice. “What are you doing here at midnight?”

She leaped to the ground and walked toward him. with her back to the moon,

until her shadow fell on the tiger. Her face was still almost invisible. She

was tall, and she stood with the natural grace of a well-bred Rajput woman of

the hills. She might be one —almost.

“Is he quite dead? Well, he deserved it. Poor old Ranjeet Singh! You know

the legend?”

She knelt. With strong weather-brown fingers she tried to close the

tiger’s staring eyes.

“He’s a man-eater.” said Blair. “He might have got you.

Tigers—snakes—leopards—don’t you know better than—”

She stood up. He could see her face

now—good-humored—half-mocking. It made him hesitate.

Pain—or it might be anger—underlay the humor. “—Any

better,” he repeated, “than to take such chances—”

“Why should you care?” she answered. He could almost see the color of her

eyes. “Blair, do you know what chance is?”

“What do you mean, Henrietta?” he said stiffly.

“I shouldn’t ask. I know the answer.” She set her foot on the tiger’s

head. “If you knew, you wouldn’t be on Wu Tu’s list of—”

“Of what?”

“Wu Tu’s sucker-list!”

She turned from him, knelt and with her fingers bared the tiger’s

fangs.

“Poor old Ranjeet Singh,” she said. “You were another bold and clever one

who lost out, weren’t you?”

Then the Rangar came, leaning on his grandson’s shoulder, and in a moment

the pool of moonlight swarmed with men who emerged like ghosts from

nowhere.

Knowledge? Ye know nothing, save ye do it without thinking.

Thought is the swamp of ignorance surrounding Knowledge. All must cross that.

Build no stronghold on it, that will sink and become a hopeless dungeon,

difficult to leave.

—From the Ninth (unfinished) Book of Noor Ali.

SOMEONE who looked like a Bat-Brahmin, ragged, arrogating

privilege but insolently careless of its obligations, spat pan-juice from a

shadow and spoke oracularly. The old Rangar gave orders, appearing to ignore

the Bat’s existence, but his feudal dignity masked experienced respect for

something older than feudalism, deeper than logic. He approached Blair:

“If your honor permits, it is wise to observe a superstition if it does no

harm. Trust me to see no whiskers are stolen. She”—he glanced at

Henrietta Frensham—“need not watch, but she should stay near. Let them

say the ghost of Ranjeet Singh is at rest.”

Blair nodded. He watched the lean shikarri pull an oiled rag through the

rifle-barrel. Then he strode over to Henrietta Frensham and sat beside her on

a rock in the moonlight.

“Will you wait while they skin him?“he asked. “I’ll send for ponies

afterward and see you back to camp.”

“Why? Is that necessary?”

“I intend to tell Grayne while I’m here about it—what I think of his

letting you roam these hills at night.”

“Is it your business? What are you doing here?” she retorted.

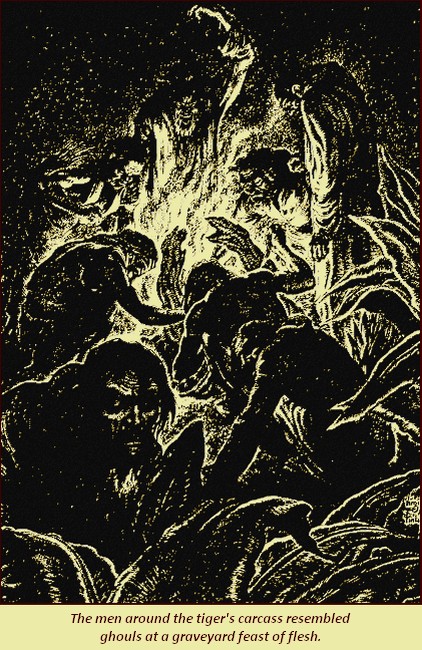

Blair looked straight in front of him. The men around the tiger’s carcass,

twenty feet away, resembled ghouls at a graveyard feast of flesh. He hardly

saw them. He was aware of—could almost feel Henrietta’s Frensham’s eyes

studying him. They were violet. Her hair was straw-gold. She held one knee

clasped in her hands, and he knew her expression, brave but vaguely mystic,

as if she expected events that she. would endure uncomplainingly for

inscrutable ends.