Frostbite (Modern Knights Book 1)

FROSTBITE

Modern Knights

Book One

JOSHUA BADER

Praise for the

Works of Joshua Bader

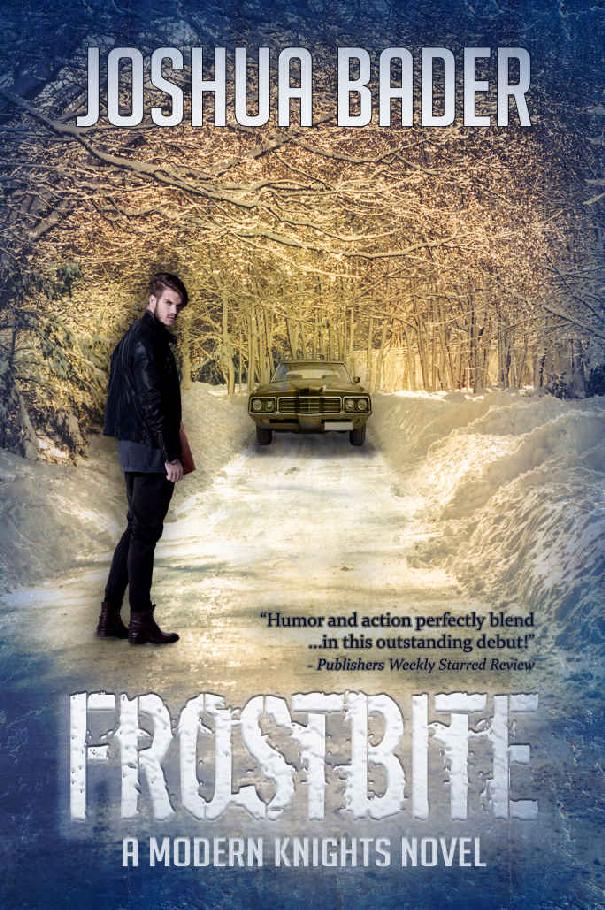

“Debut author Bader introduces readers to the Modern Knights series with an extremely impressive first novel of delicious urban fantasy with just a hint of romance. This fantastical thrill ride is filled with perfectly timed pop-culture references, stunning plot twists, and the snarky (and sometimes offensive) stylings of Colin’s inner voice. Well-researched and creatively presented humor and action perfectly blend with moral quandaries in this outstanding debut.”

- Publishers Weekly Starred Review

“I LOVED THIS BOOK. Did you see those caps? Yes, I'm that excited about it! Bader has written a great addition to the urban fantasy genre. His writing style has resulted in relatable characters who aren't all powerful (just like you and me). The resulting novel takes the reader on a wild ride from start to finish as you learn about Colin Fisher and his powers. Great stuff and can't wait for the second book!”

- GoodReads Reviewer, Cora Burke

“I must say upfront, this book exceeded my expectations! It was a thrill from beginning to end. Excellent writing, a wonderful plot, and a wonderful cast of characters kept me up longer at night than I wanted to see what was going to happen to Colin. Very highly recommend.”

- Librarian, Penny Noble

To my Dad

Who nightly introduced me to urban fantasy

Through magic rings that sent and brought back,

A horse that could talk,

And a wardrobe that sometimes led between Here and There.

- Joshua

FROSTBITE

Modern Nights: Book 1

By

Joshua Bader

***

Copyright 2016 Joshua Bader

Cover design by Tina Moss. All stock photos licensed appropriately.

Edited by Yelena Casale.

Published in the United States by City Owl Press.

For information on subsidiary rights, please contact the publisher at [email protected]

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior consent and permission of the publisher.

Part One

Conversations With The Dead

“The real problem with talking to the dead isn’t getting them to speak. It’s getting them to shut up again once they start.”

- Jadim Cartarssi, Armchair Necro-psychologist

1

With a name like Fisher, it’s only natural for me to be attracted to large bodies of water. I’m easily impressed by anything deeper than a bathtub. I grew up in Denver until I was 14. It’s a great city, especially for nature lovers, what with the ever-present mountains and an environmentally conscious population. Water, however, wild, free-standing, blue-as-the-sky, shiny-as-a-mirror, water was not Denver’s strong suit. The “lake” within walking distance of my childhood home would barely merit mention as a puddle in other places of the world. Fortunately, in the ten years since my dad sent me packing, I’ve gotten to see plenty of those other places: West Coast, East Coat, Gulf Coast, Great Lakes.

In the era of quick status updates, where everyone can define themselves by a short list of labels and in 140 characters, my status depends greatly on the perspective of the person describing me (and their degree of relatedness to me). I’ve never used Face-space or Five-corners, so I’m at the mercy of the people who do when it comes to labeling. The ones that have floated back to me are “world traveler,” “professional vagabond,” “dabbling wizard,” or “lunatic-just-short-of-civil-commitment.” My dad once used the phrase “career criminal” when he thought I was out of ear shot. Those labels all fall short of the one I prefer: Colin Fisher.

The lake stretched out in front of me was a prime example of everything that pond in Colorado wasn’t. Lake Thunderbird was man-made, but that didn’t make it any less impressive to the eye. The way the wings of the lake wrapped back around me created the illusion that I was on the edge of an island beach, rather than a hundred yards from a State Park parking lot. Sitting against the thick oak trunk, staring out across the charcoal blue waters, I felt a million miles away from all my problems. That thought, unfortunately, reminded me that I was really only 682 miles away from my most pressing issue. It would be a nine-hour drive, if I pushed straight through.

Going home to Colorado was the last thing I wanted to do. My mom died when I was 14. Dad and I did not deal with her death too well. When we weren’t crying, we were fighting. Most of the time, we fought because one of us had caught the other one crying: machismo at its dysfunctional peak. Adolescent males are crazy to start with, but the grief made me a royal pain in the ass. In my defense, my father could have been a little more supportive, more understanding. There’s no use rehashing that argument now, I suppose. There’s not enough time left to finish it.

When school let out that summer, my dad sent me to live with my aunt and uncle in Boston. The plan was I’d come back in the fall, once things settled down, got back to normal. I don’t think my dad or I ever realized that without Mom, there was no normal. If we had tried, maybe we could have come up with a new normal, but we didn’t. The last time I saw him in the flesh was at my high school graduation…in Boston, not Denver. I celebrated my twenty-fourth birthday three months ago, which made me a Cancer. My dad had cancer and was either dying or already dead.

My thoughts wandered like the wind-chopped waves on the lake, dancing through graveyards of memories better left buried and undisturbed. The book I brought out there with me was lying in the brush beside me, untouched. Most museum curators would kill me for carrying it around, let alone setting it down in the dirt, leaves, and dried mud. I’ll have to add them to the long list of people who sternly disapprove of my behavior. I picked up this peculiar tome in Charleston, chomping at the bit to read it. It’s not every day that I found a 17

th

century commentary on faeries of the Rhine plains for less than ten bucks. The owner of the antique store couldn’t read Yiddish and thought of it as a cute decorative paperweight. I thought of it as a feast of knowledge, waiting to be devoured, and I suppose both of us were right, in our own way. I probably would’ve finished studying it already, if I hadn’t called home to Boston that night.

I went to Harvard for three years. That was part of the initial allure of spending the summer with Uncle James and Aunt Celia in Massachusetts. By getting a feel for the area while I was still in high school, my dad thought it might reduce the stress of transition later. He always thought I had Ivy League potential. I guess it worked a little. My freshman and sophomore years were great. Then Sarai disappeared. I dropped out after the second semester of my junior year, a ripe old burnout at the age of 20. I’ve often wondered if my dad would have put a “My son is a Harvard dropout” bumper sticker on his car if I sent him one. As failures go, it’s impressive: aim for the stars; when you crash, you’ll make a bigger crater.

I reached for the book, anxious to face the road again and be done with it. My legs were stiff, but responsive, as I rose. In my wild gypsy days, I’ve mastered the art of sitting under a tree for long periods of time, without letting body parts fall asleep. The walk from the lakeside to my car, Dorothy, was all too short. Dorothy’s hood stretched on forever, a giant silver space-age yacht cleverly disguised as an ’86 Ford Crown Victoria. Spare me the save-the-world speech: I had her converted to bio-diesel five years ago. It’s possible to be environmentally responsible and still drive a tank.

I deposited the book onto the passenger seat, unceremoniously dumping it on top of the other unread treasures I’d acquired in the last week. My dad was lying in a hospital, parts of him slowly devouring other parts of him, but I still couldn’t force myself to hurry. My traveling routine was what it was: drive for two to three hundred miles, refuel, cruise around the town to see if anything catches my interest, then find a safe place to park the car for the night. Interest for me comes in two forms: money and knowledge. I love old books and I don’t mind a little manual labor to acquire them. I’ve been stretching my runs to 400 plus miles lately, near the edge of Dorothy’s fuel limit, and skimping on the work, but this was still the way I operated. I’ll get there when I get there. The fact that I didn’t want to watch my Dad die had nothing to do with my refusal to break routine…okay, maybe a little. Maybe a lot.

I took a deep breath, my eyes panning over the grandeur of the lake one last time, before turning the key in the ignition. I didn’t want to leave, but the road awaited. Nothing happened when I turned the key. I grimaced, frustrated by Dorothy’s sudden rebellion. Soon, she’d be the only family I had left in the world and she was trying to jump ship, too. When I noticed that the headlight knob was turned all the way to bright, I let my head crash down on to the rim of the steering wheel. I cried for far longer than a man can safely admit.

2

I don’t want to give anyone the wrong impression of me. I was burnt out, worn out, used up, and scared as hell, but I didn’t usually spend my evenings crying over a dead battery. Life may be a mean thing to inflict on a person, but we all got hit with it. Most of the time, I kept it together better than that.

Once I got my frustration out of my system, I did the only thing I could do and started walking. Most people would have called for help on their cell-phone-computer-thingamajig. I didn’t, because I didn’t own one. Most companies gave me dirty looks when I tried to give Dorothy’s license plate number as my home billing address. I could overcome that difficulty when I wanted or needed something badly enough, but an iLeash didn’t hold a lot of attraction for me. They tended to do funny things when I held them.