Read From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68 Online

Authors: H. H. Scullard

Tags: #Humanities

From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68 (45 page)

The course of events in Palestine and reports of growing discontent in the West persuaded Nero to listen to the appeals of Helius, the freedman whom he had left in charge at Rome, that he should return from Greece. He left reluctantly and reached the city early in 68. Here he found the populace angry because of a cornshortage; the aristocracy hated him, and the armies were becoming restless at his lack of interest and angered through his murder of commanders like Corbulo and those of the Rhine armies. His reception befitted an opera star more than a Roman emperor: the victor of the sacred games of Greece hung up his 1808 crowns for the public to admire. But he still longed for a Greek setting and so by March he had gone to Naples. Here news reached him that C. Julius Vindex, the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, was in revolt.

The objectives of Vindex, a Romanized Gaul, are uncertain, beyond that of getting rid of Nero: he probably had no intention of restoring republican authority nor is it clear how far he may have championed a Gallic nationalist movement which sought autonomy, or at least more freedom, for Gaul. He

probably merely wanted a better emperor. He won the support of some Gallic tribes, but others opposed him; Vienna in the Rhone valley declared for him, but Lugdunum remained loyal to Nero. Nevertheless Vindex raised a force said to number 100,000 men. All would depend on the reaction of the army commanders in the West, with whom he got into touch. Servius Sulpicius Galba, the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, responded and proclaimed himself the ‘legatus senatus populique Romani’, that is, presumably, no longer a servant of Nero. In Spain he was supported by M. Salvius Otho, governor of Lusitania, and by A. Caecina, the quaestor of Baetica. L. Clodius Macer, the legate in Africa, also revolted. He, Galba and Vindex all issued propagandist coins and began to build up their forces.

The attitude of the armies on the Rhine was critical. The legate of Upper Germany, L. Verginius Rufus, advanced against Vindex and the armies met at Vesontio (Besançon). What happened is obscure: the two leaders conferred, but Verginius’ men are said to have insisted on fighting; possibly they regarded the Gauls as dangerous nationalists. In the battle that followed Vindex was defeated and committed suicide. Verginius Rufus was immediately offered the principate by his victorious troops, but he refused, perhaps less out of loyalty to Nero than because he was of equestrian origin. Meantime Galba in Spain was left in a dangerous position and even thought of taking his life, but in June a message reached him that Nero was dead and that the Senate and Practorians had chosen him as emperor. In two famous phrases of Tacitus, ‘a secret of empire was revealed that an emperor could be made elsewhere than at Rome’, and Rome gained a ruler who was ‘omnium consensu capax imperii nisi imperasset’.

35

Resolution in this crisis might have yet saved Nero; the Praetorians were loyal and he still had troops on whom he could rely. But he hesitated and beyond making himself sole consul he did little. Tigellinus fled, and the other Praetorian Prefect, Nymphidius Sabinus, bribed the Guard with 30,000 sesterces a head to support the Senate and proclaim Galba emperor. Nero, who was hiding in the villa of his freedman Phaon near Rome, heard the news that he had been proclaimed a public enemy by the Senate. While steeling himself to strike the fatal blow he is said to have bemoaned the loss to the world of such an artist (‘qualis artifex pereo’), and when his pursuers were at last on him his freedman Epaphroditus helped him thrust his sword home. So died the last of the Julio-Claudian dynasty on 9 June 68, aged thirty.

The promise of his early years had been unfulfilled, and on his way to open absolutism and tyranny Nero had incurred great hatred in the West. In the East, however, he had been popular, except with Jews and Christians who regarded him as the anti-Christ; indeed two pretenders who emerged in the East in 69 and 79, claiming to be Nero, easily gained some temporary following. But his death did not immediately solve all problems: the lack of an heir

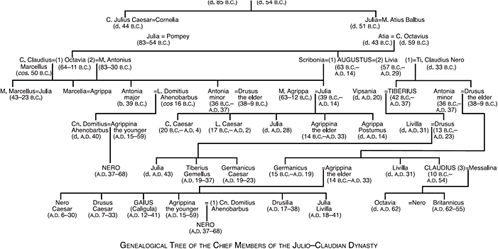

Genealogical tree of the chief members of the Julio-Claudian dynasty

undermined the hereditary principle of succession. This was decided by the army groups in mutual rivalry. In 69, the ‘year of the four emperors’, Galba, Otho, Vitellius and Vespasian succeeded each other in quick succession, but in the end the will of the armies of the East and of the Danube prevailed and Vespasian’s claims were vindicated. Since he had two sons, Titus and Domitian, Rome might look forward to a period of peace in which the succession would not again be contested in bitter civil war, and in fact the new dynasty of the three Flavian emperors served Rome well. Though the principate advanced a little farther along the path to absolutism, stable government and sound administration were again established and Rome could once more believe in herself and her future: she was given a new lease of life. Not without hope could the legend of a coin of Vespasian proclaim the promise of ‘The Eternity of the Roman People’.

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL LIFE IN THE EARLY EMPIRE

Economic life in the early Empire did not differ essentially from that under the late Republic.

1

Augustus neither introduced a new economic policy nor sought to establish State controls or monopolies: the old

laissez-faire

continued. Taxation was not used as a direct means of controlling trade or industry and its incidence was not heavy enough to hamper private enterprise. As earlier, there was little competition between the State and the individual, but rather competition was allowed to develop freely between all those who interested themselves in industry or trade. The essential difference was the establishment of the

pax Romana

: no longer were wars or civil strife to be allowed to strike crippling blows at the economic life of the community. By developing the political unity of the Mediterranean world, Augustus thereby created the conditions for its economic unification. Given peace, the economic prosperity of the Empire would take care of itself.

Italy became increasingly prosperous and dominated the economic life of the Empire. In agriculture no sudden changes took place.

Latifundia

continued and perhaps even increased in some parts, as Etruria, S. Italy, and in parts of Latium and Campania, but medium-sized farms held their own. Some of the latter in central Italy, as Horace’s famous Sabine farm, would be owned by city-dwellers, run by bailiffs, and worked in part by slaves but in part leased out in plots to tenants (

coloni

: a term that only later came to mean renters tied to the soil, or serfs). In Campania, in the farms around Vesuvius at Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae, a higher proportion of owners lived on their estates which were worked by slaves rather than by

coloni

; many owners, however,

probably a majority, also had town-houses. The main changes were in labour and produce: the independent peasant farmer was tending to disappear and to be transformed into a tenant, while wine and oil became the main products. Since grain came as tribute from Egypt and Africa, the cereal culture of Latium declined, but provincial grain probably did not seriously affect cornproduction in the rest of Italy. The population of Italy was increasing and therefore much wheat must have been grown: if its production declined, this will probably have been because viticulture often proved more profitable.

Features which became more noticeable as time passed, included the declining number of slaves, provincial competition, and the concentration of land in fewer hands. The cessation of wars and piracy naturally caused a diminution of slaves. This was offset to some extent by an increase in the number of home-bred slaves and by better treatment. Columella, the agricultural expert of Nero’s day, shows that the work of slavewomen was lightened in proportion to the number of their children and that the mother of three was entitled to her freedom. Though he implies that slaves were often bound, Pliny a little later says that he never used chained slaves. Whether farm slaves received the customary five

denarii

a month that was given to town slaves remains uncertain. More humane treatment might increase efficiency to some extent and thus help to compensate for the difficulty of obtaining slaves, but Columella gives the impression that efficiency was rare without constant vigilance. Another aspect of the Julio-Claudian period was that marketing conditions were changing: the economic development of the western provinces was progressing; Gaul, Spain and Africa were producing more wine and oil. Again, during the reigns from Tiberius to Nero imperial confiscations of land, both in Italy and the provinces, increased, while the emperor received much property by inheritance. He thus became the greatest landowner, and in general there was a tendency to concentrate land among fewer owners (Seneca, for instance, secured great estates after the murder of Britannicus), but this does not prove the truth of Pliny’s famous observation that ‘latifundia Italiam perdidere’. Some of the medium-sized and smaller estates may have been absorbed while in face of changing conditions an increasing number of large landowners may have let out more land to tenants and turned more over to cereal production. But there is enough evidence to show that the concentration of land to which Roman satirists and moralists often refer, did not occur everywhere: many small farmers in the central Apennines continued to work their own plots, and estates of moderate size flourished in Campania.

This diveristy of development in different parts of Italy, ranging from small farm to great ranch, finds a parallel in the industrial development.

Farm-households in early days naturally tended to a ‘house-economy’ and self-sufficiency; as much food, clothing and equipment as possible would be home-produced. But as towns developed, their needs would be met by the growth of industry on a small scale: cobblers, smiths and others would use their special skills for the community and establish their small workroomshops employing one or two free or servile hands, but not seeking to provide for more than their own immediate neighbourhood. But as men became more wealthy and demanded more luxuries, they created a wider market that was satisfied by the increase of commerce and of specialized lines of industrial production. Division of labour increased and something like a factory system emerged for the production of certain goods on a large scale and for wide distribution.

Thus industry ranged from home-production through the artisan-shop to the specialized factory. The first, with such activities as spinning and weaving, needs no description. The work of the small shop-factory, which might represent more than half the output in the early empire, is illustrated from the remains at Pompeii. Residential blocks, built around a central courtyard, often had their street-frontages lined with small rooms which were self-contained, i.e. they did not connect with the main block but merely opened on the street. Here worked the small manufacturer: in the front he might have a counter to display his wares, and behind was his workshop with its bench, forge or furnace where he made his cutlery, shoes or leather-work. Such retail trade conducted on the spot would be supplemented by the peddling of hawkers and street-fairs.

2

Specialization in larger factories, worked by slave labour and aiming at mass production for wider distribution or even export, increased, but really large-scale development was hampered by the cost of transport by land and by the ubiquity of slavery: not only did many wealthy men employ their own slaves on industrial work that otherwise might have fallen to the open market, but the supply of cheap labour did not encourage inventiveness in labour-saving devices that might have stimulated fresh developments. One of the most striking aspects of ‘big industry’ was the production of a red-glazed table ware, Arretine

terra sigillata

(the so-called Samian ware). This was manufactured at Arretium (Arezzo) and one or two other centres in Italy (especially Puteoli and perhaps in Rome) and gained such popularity that it was exported widely to nearly all parts of the Roman world except the southeast. The scale of production is illustrated by the fact that one mixing-basin at Arretium had a capacity of 10,000 gallons; the largest known single workshop employed 58 slaves. Since most of the decorated pieces are stamped with the maker’s name, much can be learned about the organization of the trade. The reason for the popularity of this particular ware is not of course that it was a patented trade-process (such methods were unknown) but

perhaps because of its technical excellence; the process of red-glazing may have been a trade-secret and the necessary fine clay was localized. This particular trade not only provides the best example of a factory-system producing for an ‘international’ market, but its fate illustrates another tendency. Production at Arretium began about 30 B.C., but some fifty years later the ware was being manufactured in the provinces, especially in Gaul: in order to reduce cost of transport producers apparently found it profitable either to migrate or to establish branch-factories. So flourishing did the potteries in southern Gaul become that the Arretine factories declined and virtually ceased business in the Flavian period. This change illustrates how the extreme prosperity of Italy in the early years of the Empire was gradually overshadowed in some spheres by provincial competition.

Another specialized industry was the production of glassware, which received a great impetus from the invention in Sidon of the process of glass-blowing; previously glass-paste had been poured into a mould, and a new mould had been needed for each article. Skilled workers migrated from the East to Italy and suitable sand was found on the Volturnus river in Campania. Here factories were established and specialists produced fine translucent glassware, usually signed by the maker, for export. Metal industries developed on various lines. Much ironware continued to be made by the smith at the forge in his small shop, but there was also a concentration of the iron trade at Puteoli where pig-iron was shipped from Elba and manufactured in quantity. This did not involve the bringing together of specialized skills, since each man worked much as he could have done in his own shop (and it was not until the fourth century A.D. that the invention of valved bellows improved smelting to a point where cast iron could be made), but Puteoli could provide wood for the furnaces and was an excellent distributing centre. The production of copper and bronze utensils, however, led to a truer factory system, since more varied processes and artistic skills were brought together. This was centred at Capua, which had an old tradition of metalwork; large factories employed hundreds of men, and the products were exported as far north as Germany and Britain, while nearer home much of the fine metal furniture and

objects d’art

of Pompeii came from the Capuan factories. They also produced much of the splendid silver plate that has been found at Pompeii and neighbourhood (e.g. the treasure from Boscoreale). Jewellery and goldwork on the other hand continued to be made and sold in small shops.

Bricks, though used in North Italy, were not widely used in Rome before the time of Claudius apart from roof-tiles. Thereafter brickfaced concrete became more common and after its superiority to travertine as heat-resisting had been demonstrated during the fire in Nero’s reign, it was widely used in the rebuilding of Rome and thereafter. Brickyards helped to make the

fortunes of Domitius Afer who came to Rome under Tiberius a poor man and died in 58; his descendants, using the opportunity created by the fire, almost gained control of the industry in the city, and few buildings did not contain bricks bearing the name of Afer. The business ultimately passed by inheritance to Marcus Aurelius and imperial possession, but the making of bricks had always been regarded more as part of agriculture than industry and was therefore regarded as a reasonably ‘respectable’ source of wealth.

The public and private water supply of Rome required the production of large quantities of standard lead pipes, but curiously this need did not result in the growth of factories. Two groups of imperial slaves were responsible for the aqueducts, one inherited by Augustus from Agrippa and the other created by Claudius; they had to make and lay the pipes. The water supply to private buildings and houses was provided by individuals who bought from the authorities the right to tap the public water-mains and who then laid down the pipes. The names of the makers that are stamped on these pipes indicate that they were made in small shops and not large factories. Thus here Roman conservatism preserved older methods at the expense of more efficient organization: the plumber and manufacturer were rolled into one.

During the Republic most clothing was produced at home and men wore homespun: the small shop system therefore was less needed in this industry. But the processing of such homespun woollen cloth (e.g. the elimination of the oil) was not easy and in the early Empire at latest the task was often transferred to skilled fullers. At Pompeii, for instance, there are remains of many fulleries which in addition to laundry and dyeing services helped to process cloth for individual use; a fullers’ hall on one side of the Forum suggests that they may also have bought the rough cloth and after treating it have displayed and sold it there. In some centres both in North and South Italy, however, there were some large slave-run factories for the production of finer clothing fabrics. Other materials were imported, as silk from the Far East and linen from the state factories of Egypt which Augustus inherited from the Ptolemies.

The Augustan peace naturally enabled the provinces also to improve their economic conditions. In general there is a distinction between the newer provinces of the West, which tended to supply the raw materials, and those of the East with their much older traditions of trade and industry. All produced what they could for their own needs, but most also managed to provide a little more, both of natural products and manufactured articles, for export. The products of Egypt found a wide market; they included corn (sufficient it is said to feed the population of Rome for four months), papyrus (of which Egypt enjoyed a monopoly), glass, textiles, metalware, stones and jewels. Syria supplied wine, dried fruits, spices, drugs, glass and textiles (her dyeworks were famous); and she also benefited from her position astride some

of the eastern caravan routes, and from the old Phoenician carrying trade. Asia Minor exported oil, wine, fruits, salted fish, wood, copper, precious stones and also textiles (including woollens from Miletus, goat-hair coats from Cilicia, silks from Cos, and carpets and rugs). Greece was rather poor but managed to send abroad some wine and oil and art bronzes. Sicily continued in its old role as an exporter of corn. The western provinces began to enter on a period of great prosperity. Gaul exported wine and oil from the south and corn from the north. It produced much crude metal but probably did not export much of it or of the objects manufactured from it. But it did export textiles, and, as has been seen, from about A.D. 20 began to develop its pottery industry, of which a centre was at La Graufesenque in the south; by the end of the century production was moving to the north (e.g. at Lezoux). Glass also was produced from the middle of the century at Lugdunum which had become a most prosperous trade centre. Spain, rich in minerals, was also very productive and exported gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, iron. It also sent overseas corn, oil and wine, and some specialities as pickled fish,

garum

-sauce and esparto-grass for rope-making. The discarded pottery-containers of the wine and oil were thrown on to a heap in Rome, which in the course of time became a great mound (the Monte Testaccio). The exports of Britain have already been mentioned (p. 252). Africa exported corn, oil, animals for the arena, citron wood and precious stones. The Danube lands despatched some agricultural produce and much iron (some of it manufactured) and gold. This trade passed through Aquileia in N. Italy, which became a great commercial city, balancing the harbour of Puteoli in the south.