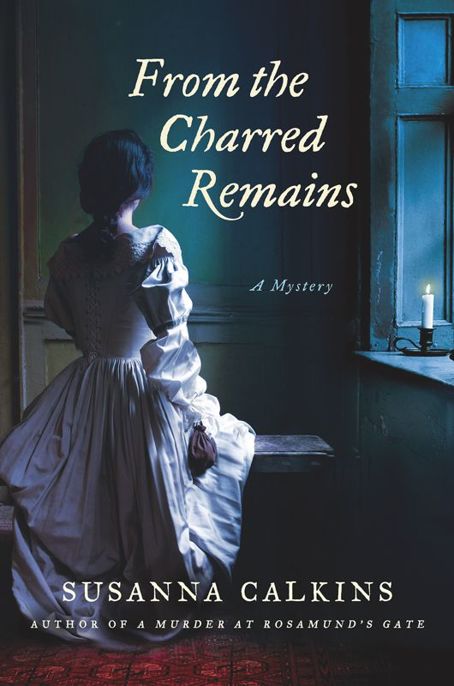

From the Charred Remains

Read From the Charred Remains Online

Authors: Susanna Calkins

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Historical, #Women Sleuths, #Amateur Sleuth

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

To Matt, Alex, and Quentin

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are many people who helped transform

From the Charred Remains

from a series of scrawls into a real book. In particular, I deeply appreciate the invaluable insights and feedback provided by my beta readers, Maggie Dalrymple, Margaret Light, Steve Stofferahn, and Shyanmei Wang, as well as Greg Light for our many conversations about writing. I must also thank my chief medical correspondents, Larry Cochard, Marian Dagosto, and Gary Martin, who painstakingly answered all my questions about corpses and bones. I’d also like to thank the lovely towns of Wolcott and Chalmers in Indiana for giving me the idea for one of my favorite character names (Wolcott Chalmers). And without coffee, I don’t know if the book would have been written; so to this end, I must thank Amy Touchette and Jill Gross for allowing me to write for hours on end in Arriva Dolce, the best coffee shop in Highland Park.

I will always be grateful to my agent, David Hale Smith, for helping make this dream a reality and for connecting me to this new world of writing and publishing. I so appreciate, too, my wonderful editor, Kelley Ragland, for her talent in helping me reflect on plot points and character motivations. I feel extremely fortunate that she cares about Lucy Campion and her world as much as I do. I’d also like to thank Elizabeth Lacks and the rest of the St. Martin’s/Minotaur Books team, including David Rotstein, the amazing artist who designed my cover, for their commitment and hard work on my book.

As always, I’m grateful for the love and support of my family, especially James and Diane Calkins, Becky Calkins, Monica Calkins and Steve Wagner, Vince Calkins, Robin Kelley and Angie Betz, and Jennie Bahnaman. To my wonderful children, Alex and Quentin Kelley, it’s been so much fun to share the silly and entertaining parts of being an author with you!

Most of all, I’d like to thank my dear husband, Matt—keeper of the thousand monkeys all typing at a thousand typewriters—for his boundless enthusiasm and love. It is to him I dedicate this novel.

CONTENTS

September 1666: After the Great Fire / London

LONDON

September 1666

After the Great Fire

1

At the clanging of the swords, Lucy’s stomach lurched and her hands tightened on her rake. The sound still made her cringe, even all these years after Cromwell’s war.

No soldiers now, but two boys garbed as knights, pitching at each other with heavy swords, their underdeveloped bodies encumbered by breastplates and armor made for men. Lucy watched the boys play for a moment, as they slid about in the rubble—the aftermath of the Great Fire—trying to stay atop the mountains of debris that once comprised London’s bustling Fleet Street.

Barely a fortnight had passed since the Great Fire of 1666 had devastated London in the three days between September 2 and September 5, leaving a sprawling, still smoldering, wasteland. Ludgate, Cheapside, St. Paul’s—all unrecognizable. Where dwellings had once pressed in on each other, like old women clinging together in market, now all was leveled. The moment one medieval structure had fallen nearly all had collapsed, as the centuries-old timber could not withstand the mighty blaze. Here and there, a few structures remained. St. Giles-Without-Cripplegate. St. Katherine Cree. London Bridge. The Tower. Perhaps licked by flames, but not destroyed.

Lucy had heard that, by King Charles’s reckoning, more than thirteen thousand homes, churches, and shops had been destroyed, leaving thousands of people without shelter or livelihoods. The real miracle was that scarcely few had perished outright, even though Lucy herself had nearly died in the early hours of the blaze. Everyone had missing neighbors though, people who’d not returned, so the death toll might still grow.

And the Fire was still not yet quenched, despite the unceasing fire brigade. In their panic, when the Fire had first started, Londoners had dug into the network of elm pipes that lay under the streets, to get at the water pumped in from the Thames. With so many punctures, the pipes did not work as they ought, and the water had ceased to flow. The horses and the pumps could not get through the narrow streets, particularly as they grew more jammed as people tried desperately to flee with as many belongings as they could carry in small carts and on their backs.

Even now, buckets of water drawn from the nearby Thames were still being passed hand to hand, from soldier to butcher to child to soap-seller, throughout the day and night, as they had been since the wind had changed on the third day and the fire had at last begun to subside. The smell of smoke still hung heavily in the air, stinging Lucy’s eyes and nose, and making her petticoats and bonnet reek.

Like hundreds of other Londoners, Lucy had been pressed into service by the King and the City government to help clear away the rubble, for a few pence a day. It was a far cry from what her life had been like up until the Fire had broken out. For the last few years, she’d been serving as a chambermaid in the household of Master Hargrave, a local magistrate, who spent many hours presiding over the assizes and other court sessions.

Well, no longer a chambermaid exactly, she reminded herself. Lucy had risen to be a lady’s maid, excepting now there was no longer any lady in the household for her to serve. Mistress Hargrave, bless her soul, had been taken by the plague last summer, and the magistrate’s only daughter, Sarah, had turned Quaker, traveling to distant lands. Since then, the master, a good and kindly man, had kept Lucy in his employ.

Truth be told, there was no clear place for Lucy in the household. Annie was the chambermaid now, having taken on Lucy’s old scullery duties, emptying chamber pots, laundering clothes, and keeping the house tidy. Cook prepared the small family’s meals, while her husband, John, tended to the needs of the magistrate and his son. Lucy did what she could, helping Cook and John keep the household running with godly order. But the knowledge that she had no clear place in the household remained heavy on her thoughts.

Clinging to order was all they could do—or so it seemed—in this world gone mad. The lawlessness and looting, rampant even before the Fire, when the great plague of the preceding two years had torn social and familial ties apart, threatened to grow worse. During the plague, many servants who had survived their masters had simply seized what they could. Some took just food or trifles, others new clothes or more luxurious items, but many had taken everything, in a quest to start their lives anew. They stole their masters’ carts, horses, homes, livelihoods, and, in some cases, even their titles. In an instant, barmaids could become fine ladies, apprentices could become masters, with no one the wiser. Most seemed to have gotten away with these deeds too. Some areas of the city had been so hard hit by the plague that there were few left alive who could gainsay these usurpers’ outrageous claims. No gossiping neighbors, no knowledgeable parishioners, no bellmen keeping careful watch. The ties of community that had so long bound Londoners to order and authority had been shattered when the plague was at its height. Only after the members of government had returned to the city had communal order and authority slowly been restored.

Yet with the Fire the world, once again, seemed completely askew. As before, people were quick to take what did not belong to them and to seek a new place in society. The ponderous thefts that had occurred during the plague had only been worsened by the Fire. Property records, wills, legal testaments, and other such documents had been swallowed by the flames, leaving many properties, trades, and livelihoods in dispute, opening the door even wider to looters and squatters.

Although Lucy would never have betrayed the Hargraves in such a base way, as so many servants she knew had done to their masters, there was something about the way these thieves had liberated themselves that she admired. The apprentices who had taken over their masters’ shops, and the servants who were now sleeping in their masters’ beds, had seized the opportunity to bury their old identities and livelihoods deep within the ashes, and to craft new lives for themselves.

For now, Lucy was just grateful that her family and most of the Hargraves had survived the plague and the Fire, although that survival had not come without cost. The chaos, the suffering, the aftermath of both events were still the stuff of nightmares.

Perhaps the prophets and soothsayers were right, Lucy thought. Maybe 1666

was

the devil’s year, as so many people fearfully whispered. Surely a judgment was being passed by the Lord.

Yet even as the thought occurred to her, Lucy pushed it out of her head. “Fantastical stuff,” she could almost hear the magistrate say. “Utter foolishness. I’m surprised at you, Lucy.”

Lucy returned to the tedious work before her. Rake. Scoop. Bucket. The men would first dismantle and carry away the fallen beams, and then remove the remains of furniture, doors, shutters, and other large materials. It was up to the women then to fill sacks and pails with debris, and empty them into the waiting carts. From there, the carts would dump everything into the Thames. Buckets of water coming up to cool the embers, buckets of debris going back.

The clanging sound of the boys started up again. “Stole that armor, I’d wager,” said the young woman at her side, commenting on the antics of the two boy knights. “Don’t you suppose, Lucy?”

Lucy glanced at Annie. As the magistrate’s chambermaid, Annie was certainly growing up, no longer the gawky scrawny girl she’d been when Lucy found her on the streets of London two years before. Though still small, her arms and cheeks were round now, and her smile was no longer so sad.

“I don’t know,” Lucy shrugged. The armor donned by the boys had likely come from a church, a family monument perhaps. Who could know? The Fire had disturbed as much as it had secreted and destroyed. “Maybe.”

Certainly, the Fire had been fickle, incinerating some objects while gently charring others. As she and Annie had raked through the rubble over the last few days, they had seen many things surface, giving little hints about the people who may have lived and worked there. A bed frame, a spinet, children’s toys, fragments of clothes, some tools, a dipper, some buckets, a laundry tub, a few knives, all a jumble of life and humanity. They had even uncovered a pianoforte. With one finger, Annie had tapped on one of the grimy ivory keys, and Lucy had winced at the discordant jangling sound that had emerged from the once precious piece.

Here and there they found bits of treasure too. A silver mirror, blackened and peeling. Some gold coins, blackened and distorted from the flames. All those involved with the shoveling and the raking had been warned not to pocket any items they found. Strict laws against looters had been passed and the King’s soldiers monitored the ruins to ensure that merchants, landowners, and tenants did not lose their property or their rights. For her part, Lucy wanted nothing from the Fire, seeing that it had only brought misery, despair, and chaos.