Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream (31 page)

Read Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream Online

Authors: H. G. Bissinger

Tags: #State & Local, #Physical Education, #Permian High School (Odessa; Tex.) - Football, #Odessa, #Social Science, #Football - Social Aspects - Texas - Odessa, #Customs & Traditions, #Social Aspects, #Football, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Sports Stories, #Southwest (AZ; NM; OK; TX), #Education, #Football Stories, #Texas, #History

When Tony was Brian's age the thought of college, any college, was as funny as it was ridiculous. Just getting through

high school was miracle enough, and the way Tony and most

other kids from South El Paso looked at it, everything after that

in life was gravy, a gift.

He entered the army in 1964 when it became clear that if he

didn't join the military and get off the streets, something serious was going to happen. Tony was stationed in Germany. He

got drunk one night, took a truck without authorization, and

hopped from town to town until he wrecked it. He wasn't court-

martialed, but he was stripped of his rank and confined to the

base for six months.

"It scared the shit out of me," he remembered, and he'd decided he'd better straighten up. He went to various army missile schools and intelligence schools and communications

schools. For the first time in his life he realized that he wasn't

born to be a delinquent but actually had some smarts, or else

the army was filled with exceptionally stupid people. "It was

amazing how dumb these motherfuckers were," he remembered. He came out of the army and went back to El Paso without any idea of what he should do. He got a job as an electric

meter reader, and then he saw an ad in the newspaper for

openings in the El Paso police department.

He became a cop in 1967 at a time when just about every one in the world hated cops. It was a fascinating, bizarre line

of work that he was perfectly suited to because of his street

smarts and not so suited to because of his liberal outlook, and

he quickly realized that 50 percent of his colleagues "had no

business carrying a fucking gun." He worked patrol for five

years, then became a detective in vice and narcotics, then made

sergeant.

In the meantime he had gotten married, and right after his

first child, Adrian, was born, he decided to go to college fulltime to get a degree. He worked the late shift as a cop from

eleven at night to seven in the morning, showed up for class at

the University of Texas-El Paso an hour later, went all day with

a full course load, got in a few hours' sleep, and then went back

to the late shift. He majored in political science and English and

by going year-round he graduated in three years. He never had

a weekend off during that period, and looking back on it, he

didn't know how he had done it. But something was pushing

him. If the opportunity was there to get a college education

under the G.I. Bill, he figured he might as well take advantage of' it.

He came up for lieutenant, but then he decided to quit the

police department altogether and go to law school. He went to

Texas Tech University in Lubbock at the age of twenty-nine.

When he graduated from law school in 1978, he had hoped

to get a job in neighboring Midland instead of Odessa. On his

trips between Lubbock arid El Paso he drove through Odessa,

down the hodgepodge of Second Street with its junkyards and

cheap motels and auto supply stores, across Andrews Highway

with its endless row of fast-food restaurants and corrugated

warehouses, and he thought the town was dirty and seedy and

trashy. But the district attorney's office made him a job offer

even though he didn't have his license yet, and he accepted it.

He was the first Hispanic lawyer ever to work for the office, and

he later found out why the offer had been made so quicklythe office had come under a lot of heat for its investigation of

the death of 'a Hispanic inmate in the county jail. Several wit nesses claimed he had been beaten to death. The allegation was

never substantiated, but the office needed a token Hispanic

fast, and Tony was it. He worked in the district attorney's office

for two years and then opened a criminal practice of his own.

It became a gold mine. Seventy percent of his clients were

Mexican-American, and much of his work was in the lucrative

area of drug-related cases. In 1982 he moved his family from

an apartment to a house in the most elite section of town, the

Country Club Estates.

His law practice thrived and soon Tony Chavez had it all,

money, a six-figure income, a fancy house with a pool, fine cars,

an American Express Platinum card. When he was growing up

he had never once gone out to dinner with his parents or to the

movies. He lavished his sons with all those things and much,

much more, trips, jewelry, a brand-new RX-7 sports car for

Brian that took him less than a week to crack tip in a mall parking lot.

His life seemed the embodiment of the American Dream, living proof that anything could happen if a person had enough

drive and a willingness to take risks. But Tony had never forgotten where he came from. Beneath the successful lawyer

was still a kid on the run in South El Paso-a little boyish, a

little roguish, a little unorthodox, a little iconoclastic, and he

didn't feel imperial or privileged because of what had happened to him.

He had done well in Odessa. He had come at a time when it

was impossible anymore to ignore Hispanics, and he made

good from that circumstance. He and his family had assimilated as well as any Hispanic family in town had, but there were

still signs of subtle and not-so-subtle racism.

Even now it was still hard for Tony to get used to many of

the popular values of the place-the love for Reagan, the rise

of the religious right with what he felt to be its thinly disguised

hatred for blacks and Hispanics and homosexuals, the hue and

cry in favor of the death penalty, the way people had no tolerance for others who were less fortunate.

"They treat Reagan like he's a saint," he said. "He never went

to church. They look at him like a family man. His family hates

him. They think he's a war hero. The only place he was a war

hero was in the movies." He sometimes wondered if the country had lost its moral center, its sense of benevolence. He had

come to Odessa at the height of the boom. He had seen men

with fourth-grade educations who could barely read making

money hand over fist, and he saw the place overcome by decadence and greed until the bust.

Because of the success of his son Brian, he had become as

faithful a devotee of the Permian football program as anyone.

He went to all the games and made all the Tuesday night

booster club meetings. He went to the annual steak feed, where

the coaches and the booster club board sat at long tables inside

a warehouse and ate delicious slabs of rib eye as thick as a Bible.

He sat in the stands of Memorial Stadium cheering and clapping and feeling delighted as the Permian Panthers destroyed

the vaunted Midland High Bulldogs. He wore the same black

garb as everyone else, and he admitted that he was to some

extent living vicariously through his son, who was doing something that he had never done in South El Paso.

But despite these common characteristics he was different,

very different from those who surrounded hinm-in background, in what he believed in and what he did not. And despite his own conversion to Mojo he seemed not to understand

it all quite, the devotion, the obsession, the way some people

clung to it as if there was nothing else in life. But he also knew

it had become a kind of sacred value.

"When Permian football goes in Odessa," he said with it laugh

late one night, "then everything will go."

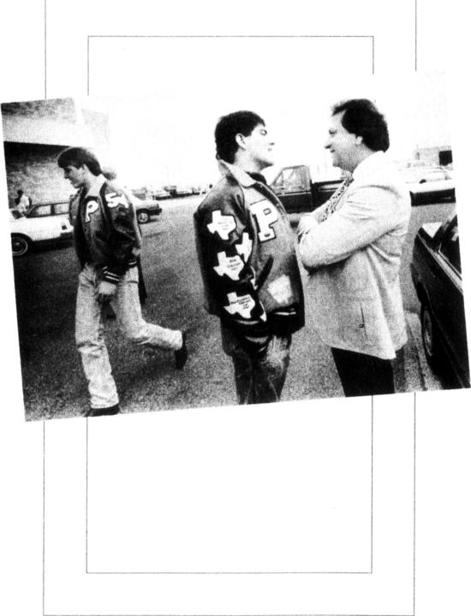

Permian scored again to make it 42-0, and some of the starters

stood on the benches behind the sidelines, finally able to relax.

The win raised their record to four and one overall and a perfect two and zero mark in the district. They were on top now

and it didn't seem possible for anyone to catch them. They had their helmets off and they looked like a row of beauty queens.

There was Chad Payne with his hands on his hips and his chiseled California surfer good looks, the hard jaw, the opaque

eyes, the blond hair. There was Chavez, who wasn't scared anymore but was laughing uproariously after a wonderful performance. There was Billingsley, who after another good night

with ninety-four yards rushing on twelve carries, now had his

mind on more important pursuits, like what party to go to and

what girl to charm and who might be worth fighting if he got

drunk enough. There was Stan Wilkins, who had played a heroic game despite a painful thigh bruise that required a special

pad and wasn't helped at all by the medication he had been

given because it made him throw up. They smiled and laughed

and turned to wave at proud parents and proud fans.

All around them the world seemed to be caving in; the way

of life that had existed in Odessa for sixty years was badly

shaken. Wherever you looked the economic news for this already hard-strapped area was dismal. Echoes persisted of the

1986 crash, when the area had become a scavenger hunt for

repossessed Lear jets, Mercedeses, mobile homes, oil rigs,

ranches, and two-bedroomn houses with walls so thin they

seemed translucent. The very day of the game, oil prices, the

bread-and-butter benchmark of everyone who lived here, had

skidded to $13.25 a barrel, their lowest level since August 1986

and far from that of the halcyon days of' 1981 when $35 a barrel oil had made this part of the country a combination of Plato's Retreat and the Barnum and Bailey Circus.

The same day, federal regulators announced they were spending $2.49 billion to rescue six Texas savings and loan institutions that had finally fallen under the weight of the crash in oil

prices, and everyone knew that that was just the tip of the iceberg. On the immediate local front, reports showed that rental

rates for apartments in Odessa had dropped 10 percent and

occupancy rates 8 percent, boding disaster for a market that

was woefully overbuilt from the boom. In addition, a news report showed that over the past six years the number of em ployed workers in Odessa had dropped by 22,400, from 65,200

to 42,800.

But here in Memorial Stadium in Midland, where a nearsellout crowd had gathered to watch a high school football

game, none of that seemed to matter. The joyous swells of the

band, with no note ever too loud or too off-key, the unflagging faith of the cheerleaders and all those high-octave cheers

served up without a trace of self-consciousness, the frenzied

screams of grown men and women as the boys on the field rose

to dizzying, unheard-of heights-little was different now from

how it had been almost forty years ago when a young businessman had sat in this very stadium.

It was the most feverish Friday night of the season: Odessa against

Midland, the grudge game to settle bragging rights between the two

towns for the next twelve months. There was an ove7flow crowd of

twelve thousand-plus fans in the stadium, rattling the stands from the

opening kickoff. Our guest put his hands to his ears, then shook his

head. [We] could empathize ... it would take us several seasons, living

in both Odessa and Midland, before we understood the game, not as we

knew it back east but West Texas-style as a quasi-religious experience.

The man who wrote those words never forgot that moment

in the stands. It gave him a valuable insight, one that he would

find useful at another point in his life. By conjuring up an image of America as simple and pure as the scene of pomp in

Memorial Stadium, by telling people that he was no different

from any of them sitting in those packed stands and rooting for

the Bulldogs or the Panthers, that he understood exactly how

they felt and how they thought, about Friday night football,

about life, about religion, about America, he managed to become the president of the United States.

II

II