French Classics Made Easy (9 page)

Read French Classics Made Easy Online

Authors: Richard Grausman

VARIATIONS

E

GGS

M

AGDA

[OEUFS MAGDA]

Replace the truffle with 1 tablespoon chopped parsley, 1 teaspoon Dijon mustard, and 2½ to 3 ounces (¾ to 1 cup) grated cheese, to taste. Classically, Gruyère is used, but I like to use any one of a number of other cheeses, such

as St.-Nectaire, Beaumont, or Brie. The softer cheeses cannot be grated, but should simply be diced or cut into small pieces and added to the eggs. Omit the standing period in step 1.

C

AVIAR

-T

OPPED

S

CRAMBLED

E

GG

C

UPS

[OEUFS BROUILLÉS EN SURPRISE AU CAVIAR]

Because the portions of this variation are smaller, it will serve 8 instead of 4. Replace the truffle with 2 teaspoons chopped chives and eliminate the standing period in step 1. To serve this dish as restaurants do, you must cut the tops off the eggshells, empty the eggs into a bowl, and then wash the shells so you can use them as serving containers. If you can manage this delicate operation (there are soft-boiled egg cutters on the market that work), fill the shells three-quarters full of the scrambled eggs and top each one with 1 teaspoon of sturgeon, whitefish, or salmon caviar. A simpler presentation is to serve the eggs in small ramekins.

S

LOW

-S

CRAMBLED

E

GGS AND

C

HIVES

[OEUFS BROUILLÉS À LA CIBOULETTE]

Replace the truffle with 3 tablespoons chopped chives and eliminate the standing period in step 1.

OMELET WITH HERBS

[OMELETTE AUX FINES HERBES]

MANY PEOPLE shy away from making omelets, feeling that they involve difficult techniques and a special pan. It is true that until the advent of nonstick surfaces, it was essential to have a well-seasoned omelet pan. Often the mere description of the seasoning process was enough to discourage a prospective omelet maker. But with a nonstick pan and the simple technique used here, omelet making should not be intimidating.

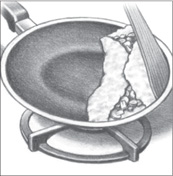

There are numerous approaches to omelet making, but I find that the technique that produces the best texture in the eggs is something I call the “stir-and-shake” method. The object is to keep the eggs moving (if the egg is allowed to sit too long over heat, it becomes hard and tough). When the eggs first hit the hot pan, I rapidly stir them off the bottom of the pan (as you would in making American-style scrambled eggs), at the same time shaking the pan gently. Then when the eggs are nearly set, I stop stirring and let the bottom of the omelet set, shaking the pan once or twice to keep it from sticking.

Everyone seems to have his own “secret” for making a light omelet. Some chefs add water or milk. (I know one who adds Tabasco sauce and swears by it.) I find that water or milk makes the eggs thinner, which might seem to be lighter, but to me, the only “secret” is working rapidly so the eggs do not toughen.

H

OW TO

F

OLD AN

O

MELET

: A French technique

American omelets are folded in half, whereas a French omelet is folded in thirds to encase its filling in a neat package. A professional chef folds an omelet and flips it out of the pan in one seamless motion, and you will, too, once you understand the following simple steps.

1.

Stir the eggs until they are nearly set. Stop stirring and let the bottom of the omelet firm slightly.

2.

Place the filling, if using, across the center of the omelet.

3.

Push the omelet forward so the opposite side rises up.

4.

Fold the risen portion to overlap the first fold.

5.

With your hand grasping the handle of the pan from underneath, turn the omelet out folded side down onto a serving platter.

OMELET PANS

An omelet pan has sloping sides, and the most popular size is 7 or 8 inches, which will make a 2- to 3-egg omelet. Even better for a 2-egg omelet is a 6-inch omelet pan. You can use larger pans to serve more people, but if you are a beginner, the smaller pan will be easier to work with. If I’m serving more than two people, I almost always use a smaller pan and make several omelets.

An

omelette aux fines herbes

is one of the most popular omelets in France and one of the finest omelets I have ever eaten, but only when fresh herbs are used. It serves one as a main course or two as a first course.

SERVES 1 OR 2

3 eggs 1

teaspoon chopped fresh tarragon

1 teaspoon chopped fresh chives

1 teaspoon chopped fresh chervil or parsley Pinch each of salt and freshly ground pepper

½ tablespoon butter

1.

In a bowl, beat the eggs with the chopped herbs, salt, and pepper until just blended.

2.

Melt the butter in a 7- to 8-inch nonstick omelet pan over medium-high heat.

3.

Add the egg mixture to the pan and rapidly and constantly stir it with a wooden spoon or silicone spatula. If you can, gently shake the pan at the same time. When the eggs are nearly set but with a little liquid still remaining (you will see the bottom of your pan as you stir), stop stirring and shake the pan for a couple of seconds, making sure that the bottom of the pan is completely covered by the egg. At this point the eggs should be set, yet still moist. Stop shaking the pan and allow the bottom of the omelet to firm slightly, 4 to 5 seconds. (After making several omelets, you will be able to stir and shake the pan simultaneously.)

4.

Fold the omelet into thirds by lifting the handle and tilting the pan at a 30-degree angle. With the back of the spoon or spatula, fold the portion of the omelet nearest the handle toward the center of the pan. Gently push the omelet forward in the pan so the unfolded portion rises up the side of the pan. With the pan now flat on your cooking surface, fold this portion back into the pan, overlapping the first fold. Grasping the handle of the pan from underneath, turn the omelet out onto a serving plate so it ends up folded side down (see “How to Fold an Omelet,”

page 37

). Serve immediately.

TURKISH OMELET

[OMELETTE TURQUE]

An omelette turque is a good example of a filled omelet, in which the flavorings are not mixed with the eggs but folded inside the cooked omelet. If you are lucky enough to have duck, squab, or pheasant livers, use them in place of the chicken livers. It serves one as a main course or two as a first course.

SERVES 1 OR 2

1½ tablespoons butter

1 shallot, chopped

3 chicken livers, cut into chunks

Pinch of fresh or dried thyme

Salt and freshly ground pepper

2 tablespoons Madeira

2 teaspoons Meat Glaze (optional;

page 309

)

3 eggs

1.

Melt 1 tablespoon of the butter in a 7- to 8-inch nonstick omelet pan over medium-high heat. Add the shallot and sauté until softened but not browned. Add the livers and sauté just until all sides are colored. Season with the thyme and 1 or 2 pinches of salt and pepper, to taste.

2.

Add the Madeira and flame, if desired (see “How to Flambé,”

page 282

). Cook to reduce the liquid by half. Add the meat glaze (if using). Toss the livers just to coat with the sauce (the livers should still be pink in the center), and remove from the heat. Using a slotted spoon, separate the livers from the sauce and keep both warm while you make the omelet.

3.

In a small bowl, beat the eggs with a pinch of salt and pepper until just blended.

4.

Wipe out the omelet pan, add the remaining ½ tablespoon butter and reheat over medium-high heat.

5.

Add the egg mixture to the pan and rapidly and constantly stir with a wooden spoon or silicone spatula. When the eggs are nearly set but with a little liquid still remaining, stop stirring and shake the pan for a couple of seconds, making sure that the bottom of the pan is completely covered by the egg. At this point, the eggs should be set, yet still moist. Stop shaking the pan and allow the bottom of the omelet to firm slightly, 4 to 5 seconds. (After making several omelets, you will be able to stir and shake the pan simultaneously.)