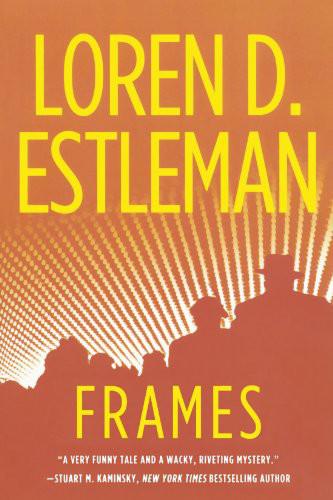

Frames

| Frames | |

| A Valentino Mystery [1] | |

| Loren D. Estleman | |

| Forge (2007) | |

| Rating: | *** |

| Tags: | Suspense |

Enter Valentino, a mild-mannered UCLA film archivist. In the surreal world of Hollywood filmdom, truth is often stranger than celluloid fiction. When Valentino buys a decrepit movie palace and uncovers a skeleton in the secret Prohibition basement, he's not really surprised. But he's staggered by a second discovery: long-lost, priceless reels of film: Erich von Stroheim’s infamous

Greed

.

The LAPD wants to take the reels as evidence, jeopardizing the precious old film. If Valentino wants to save his find, he has only one choice: solve the murder within 72 hours with the help of his mentor, the noted film scholar Broadhead, and Fanta, a feisty if slightly flaky young law student.

Between a budding romance with a beautiful forensics investigator and visions of Von Stroheim’s ghost, Valentino’s madcap race to save the flick is as fast and frenetic as a classic screwball comedy. A quirky cast of characters, smart dialogue and a touch of romance make this Estleman's most engaging and accessible novel to date.

Having appeared in 10 short stories in

Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine

, self-described film detective Valentino, who works as a film archivist at U.C.L.A., makes his novel-length debut in the engaging first of a new series from Shamus-winner Estleman. Valentino stumbles on the find of a lifetime when he inspects the Oracle, a decaying 1920s movie theater he's considering purchasing. An abandoned storage room contains reels of film that may be the only surviving prints of Erich von Stroheim's legendary epic,

Greed

. The further discovery of a skeleton of unknown vintage in the old building complicates matters. Aided by academic colleagues, Valentino tries to eat his cake and have it, too, by cooperating with the police inquiry into what might be a case of foul play without revealing the existence of the film reels, which he fears might be damaged if seized as evidence. While the lighthearted tone is far removed from the gritty realism of the author's Amos Walker series (

American Detective

, etc.), the versatile Estleman has crafted yet another intelligent page-turner.

(May)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Starred Review

Genre veteran Estleman debuts a new and wonderfully entertaining series starring a UCLA film archivist. Departing dramatically from the classic hard-boiled style of his Amos Walker novels, Estleman has concocted a jaunty, thoroughly endearing screwball comedy-mystery in which the aptly named archivist Valentino teams with a venerable film historian and a hip, slightly loopy grad student to solve a murder, rehab a movie palace, and restore a long-lost, uncut print of the Erich von Stroheim classic Greed. It all starts when Valentino buys the crumbling theater and finds the abandoned reels of von Stroheim’s film in a walled-off storage room. Unfortunately, there is also a skeleton in the closet, the remains of a long-ago murder, and the police demand that Valentino surrender the film canisters within 72 hours or face prosecution. That leaves him three days to solve the crime or risk having the police mishandle and potentially ruin the fragile film. As Valentino and his buddies careen about Los Angeles, visiting a home for retired movie workers and researching the provenance of the movie palace, Estleman smoothly seeds the text with all manner of fascinating details relating to the history of silent films and the techniques of modern film restoration. There’s even time for a nifty romance between Valentino and an LAPD forensics investigator. Great cast, great subject, flawless delivery from a real pro. --Bill Ott

~ * ~

Frames

[Valentino 01]

Loren D. Estleman

No copyright  2013 by MadMaxAU eBooks

2013 by MadMaxAU eBooks

**

That’s part of your problem. You haven’t seen enough movies.

All of life’s riddles are answered in the movies.

—Steve Martin to Kevin Kline,

Grand Canyon

(1991, Lawrence Kasdan and Meg Kasdan)

**

A NOTE TO THE READER

... in which the author owns up to using broad license in his description of the UCLA Film Preservation Program. The laboratory and its equipment here are state of the current art, and may in fact be either less or more advanced depending on the funds available when the book appears; and the building itself is an architectural fantasy. Certainly the size of the archival staff exceeds two, and its own offices are more modern and ergonomic. Who among us is inclined to be more sympathetic toward characters who haven’t squalid conditions to rise above?

**

I

POPCORN

PALACE

**

CHAPTER

1

YOU COULDN’T LIVE a linear life in Hollywood. Everything was a special effect.

One moment there you were on your fleet of telephones, bellowing at brokers and bank managers, a gravel-voiced captain of industry in a screwball comedy, and then your vision swam and someone made broad circling motions on a harp, and the next moment you were lying on a stingy mattress in a rancid hotel room with a revolver in your hand.

“Tragic case,” the realtor said. “Are you familiar with the details?”

Valentino nodded and took a hit from his five-dollar cup of coffee. He and the woman were standing in front of a bas-relief in bronze of Max Fink’s bald sad face on a plaque in the crumbling lobby of The Oracle, a ruin left over from the lost ancient civilization of Hollywood. The floor was littered with horsehair plaster and shattered chestnut shells, the plunder of some squirrel cineaste.

“Tragic, and not uncommon. He wasn’t the only entrepreneur of his time to get caught in the pinch between the Wall Street crash and the talking-pictures revolution.” He smiled apologetically at the realtor, Anita Somebody. “I’m a bore on this subject. Ask me how to spell DeMille and I’ll recite his complete filmography.”

She hesitated just long enough to convince him she didn’t know DeMille from

Deliverance.

She was a carefully preserved blonde in her forties, and Valentino knew her story without asking: She’d come out from Omaha or someplace like that twenty years ago, hoping for a role on

L.A. Law,

and when that missed the mark and she couldn’t get work in commercials, it was either realty or prostitution. Prostitution didn’t come with a dental plan. She looked obscenely well pressed in her agency blazer and tailored skirt among the rat droppings. “It’s what you call a fixer-upper,” she said.

“It’s what I call Ground Zero.”

The grand foyer was a jungle of exposed wires and broken fretwork. An ambitious spider had erected a web of Babylonian proportions across the marble staircase and pigeons fluttered to and fro among the copper coffers in the ceiling. How the building had managed to escape demolition in a city of soaring property values and cheap Mexican labor was one for Charlie Chan.

Valentino, who knew less about construction and repair than Anita knew about Cecil B. DeMille, said, “Explain to me again why you brought me here. I’m looking for a place to live, not a lifelong hobby.”

“The budget you gave us presented challenges. This neighborhood’s zoned commercial and residential. No one seems to know just where the break is. Developers are reluctant to make an offer until the county board straightens it out, and the owners are anxious to sell. I’m afraid it’s either this or Oxnard.”

“I can’t afford it.”

“You haven’t heard the asking price.”

“I don’t mean that. I love these wonderful old barns; they’re in greater danger of extinction than the spotted owl. If I bought it, I’d feel obligated to restore it to its original splendor. Did I mention I’m on salary at UCLA?”

Her lipstick smile was firmer than the foundation. “Why don’t you postpone your decision until you’ve seen all there is to see?”

“Well, I guess I can afford a tour.” Saying it, he felt an intoxicating mix of anticipation and surrender. History was his weakness and his calling.

Max Fink’s very public dream of 1927 turned into a hangover two years later, but by then everyone else was too busy taking aspirins to notice.

Fink had stumbled into millions in 1912, when he rented out his candy store in Brooklyn evenings and weekends for the exhibition of silent motion-picture shorts. When he came by one night after closing and saw how many people had lined up to pay to see painted Indians chasing covered wagons across the New Jersey countryside, he evicted his tenants, bought a projector, struck a deal with a local photoplay distributor, and went into show business.

When Thomas Edison sued his moviemaking competitors for infringing on his patent, Max Fink fled with them to Southern California and invented Hollywood. Along the way he stopped at choice locations to purchase vaudeville theaters in financial trouble and converted them into movie houses. Fifteen years after he sold his last Jolly Roger, he invested his profits in the stock market and used his credit to build a glittering chain of motion-picture palaces from coast to coast, saving the biggest and best for Los Angeles.

The Oracle as sketched by the architect was a Balinese-Turkish-Grecian temple, with a mild Polynesian influence and bits cribbed from Moorish Spain, Renaissance Italy, and the Gaiety Music Hall in Flatbush. Seating was designed for five thousand, with space in the pit for a hundred-piece orchestra. Fink commissioned a four-manual Wurlitzer pipe organ to accompany the action on-screen, a half-ton chandelier, and plaster Pegasuses to flank the grand staircase rising to the mezzanine. When word reached H. L. Mencken, the curmudgeonly magazine mogul quipped, “It just shows you what God could accomplish if He had bad taste.”